BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY Growing up black: Dennis Morris's portrait of the 70's

The photographer's pictures of black Britons during the 60's and 70's capture a period of seismic change that we can only really understand now

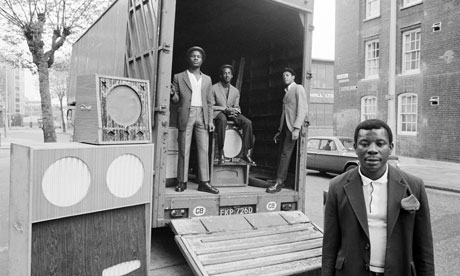

'Admiral Ken with his Box Men', Hackney 1973 Photograph: Dennis Morris

'The way we see things is affected by what we know and what we believe," wrote John Berger in Ways of Seeing. "The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled."

We know that Britain's official story – the one it keeps telling itself – is that it is a tolerant country with regards to race. This tolerance is not regarded as a work of progress but as an enduring expression of Britain's innate genius. This toleration had limits. It endured the presence of "different" kinds of people so long as they didn't make a difference.

"We are a British nation with British characteristics," explained Margaret Thatcher in 1978, during the same interview that she warned of Britain being "swamped": "Every country can take some small minorities and in many ways they add to the richness and variety of this country. The moment the minority threatens to become a big one, people get frightened."

And even as the central focus of the nation's anxieties shifted from Caribbeans to Muslims, from race to religion and from colour to culture, this essential quality remained firm. "We should talk, and rightly so, about British values that are enduring," argued Gordon Brown in 2005. "Because they stand for some of the greatest ideas in history: tolerance, liberty, civic duty, that grew in Britain and influenced the rest of the world."

But what we see in Dennis Morris's pictures of black Britons in the 60s and 70s – collected together in a new book – both challenges the limitations inherent in that framing and provides a counter-narrative to it. For in the photographs of people at church and at play, styling and protesting during this critical period in our racial history he transforms black Britons from objects to subjects and recipients of hospitality to cultural agents. We see not just a group of people shaped by their presence in Britain but shaping it: not content with being tolerated by "hosts" they demanded engagement in their new home.

The 70s were a pivotal period in black British history. When people started arriving in large numbers after the second world war, most planned to stay only long enough to earn some money and go back "home". But as Berger wrote in the Seventh Man: "The gold fell from very high in the sky. And so when it hit the earth it went down very, very, deep." So they stayed, married and raised families.

Morris's pictures illustrate the period in which black Britons, as a whole, moved from a state of transience to permanence. No longer just an immigrant community the children in these photographs have the task of reconciling the apparent contradictions between race and place. To them falls the burden of becoming British while remaining black, matching the colour of their skin with the crest on their passport – not just about the right to be in the country, but to stay in it, not just to survive but to thrive. To this generation was bequeathed the task not only of salvaging their own scattered and forgotten histories but relating to the rest of Britain how their shared histories made their presence possible. "We are here because you were there," explained Sri Lankan-born novelist, and director of the Institute of Race Relations, A Sivanandan, outlining the colonial ties that bind. The political rally cry of the time: "Come what may we're here to stay."

Throughout we witness the influences of Paul Gilroy's Black Atlantic at work. Flat caps and pork pie hats, small children dressed for church like little Lord Fauntleroy, platform shoes, flares long collars, head-wraps, miniskirts, cricket whites, rallies to support American political prisoners, The Carib Club and Gregory Issacs.

The mixed-race wedding, and various photographs of white people at social events are testimony to the fact that while this may have been a somewhat autonomous project it was by no means an independent one. Even in areas where there was a high concentration of black people, such as Hackney where these pictures were taken, the black experience was never segregated.

But this next generation could not fashion this culture out of whole cloth. "Men make their own history," wrote Karl Marx in the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. "But they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under given circumstances directly encountered and inherited from the past."

The Caribbean, to which many if not most of this generation maintained more than an emotional connection, was undergoing a period of cultural assertiveness and political turbulence. Globally it was a decade in which the Caribbean punched well above its demographic weight. In 1972 came the release of Jimmy Cliff's The Harder They Come; in 1973, the formation of Caricom, the Caribbean Community; in 1975 the release of No Woman No Cry, Bob Marley's first hit outside of Jamaica, marking the emergence of the first third world superstar. And in 1976 the West Indies cricket team thrashed England at the Oval. I was seven at the time, and I remember well the phone ringing in Stevenage as the small local Caribbean community celebrated every wicket that fell and six that was struck and my mother, standing at the door, shouting at me halfway up the street that "Brian Close had gone".

A year later there was the battle of Lewisham, where the mobilisation of the National Front was met with fierce resistance. In 1978 came Steel Pulse's album Handsworth Revolution suggesting these expressions of cultural resistance had travelled and could translate. Notwithstanding Jamaica's explosive, violent and dysfunctional domestic politics at the time, all this added confidence to the notion that "we" had something valuable with which to engage.

Where Britain was concerned those circumstances were inauspicious. The 70s were a period of particular upheaval – a decade in which post-colonial Britain too found itself in a traumatic and profound transition. There were four elections, blackouts, an IMF bailout, massive strikes, mass unemployment, 25% inflation. With punk rock in the ascendancy, the anthem for a young, mostly white, generation could be heard in the main refrain of the Sex Pistols' hit God Save the Queen: "No future, no future, no future for you."

At the very moment when black youths were trying to imagine new beginnings, the very certainties on which the lives of many white working-class youths were founded – full employment, subsidised housing, state economic intervention – were coming to an end.

That decade came to a close with the election of Thatcher, whose victory was aided in no small part by her crude appeal to white anxieties over immigration, heralding a more overtly antagonistic racial landscape for the 80s.

"Minorities are the flashpoint for a series of uncertainties that mediate between everyday life and its fast-shifting global backdrop," writes Arjun Appadurai in his book Fear of Small Numbers. "This uncertainty, exacerbated by an inability of states to secure economic sovereignty in the era of globalisation, may translate into a lack of tolerance of any sort of collective stranger."

And so it was that the efforts to establish existential legitimacy were complicated and interrupted not just by the rise of the extreme right but by a popular racist discourse that found free rein in the press. The contempt in which the black British community was held at that time, the limits within which they were tolerated and the apparent precariousness of their presence in the mediated landscape was exemplified by coverage of the Notting Hill carnival.

In 1977 the Express's front page read: "War Cry! The unprecedented scenes in the darkness of London streets looked and sounded like something out of the film classic Zulu."

"If the West Indians wish to preserve what should be a happy celebration which gives free rein to their natural exuberance, vitality and joy," argued the Mail on 31 August 1977, "then it is up to their leaders to take steps necessary to ensure its survival."

The Telegraph blamed black people for being in Britain in the first place, declaring: "Many observers warned from the outset that mass immigration from poor countries of substantially different culture would generate anomie, alienation, delinquency and worse."

That the carnival had emerged as a response to race riots in the 50s and is now the largest street carnival in western Europe is testament to how far things have shifted. That "black culture" would be blamed for the social unrest that erupted in around England in 2011 is an indication of how far we still have to go.

What was once feared as an emblem of the foreign incursion into our national identity is now embraced and even marketed as a sign of our modernity. Britain's diversity was central to the marketing in our successful Olympic bid, even if the day after the result was announced the terrorist atrocities of 7/7 put multiculturalism back in the dock. This did not happen because people just thought it was a good idea or, more bizarrely still, because it came naturally to the British temperament. It happened because it was fought for, by black and white, until our absence, not our presence, was unimaginable.

There was nothing inevitable about that outcome. Morris's images reveal a community in unself conscious flux and renewal.

The fact that its continued existence is no longer contested and, when it comes to market British modernity even celebrated, is not a function of tolerance, but of endurance and struggle.

No comments:

Post a Comment