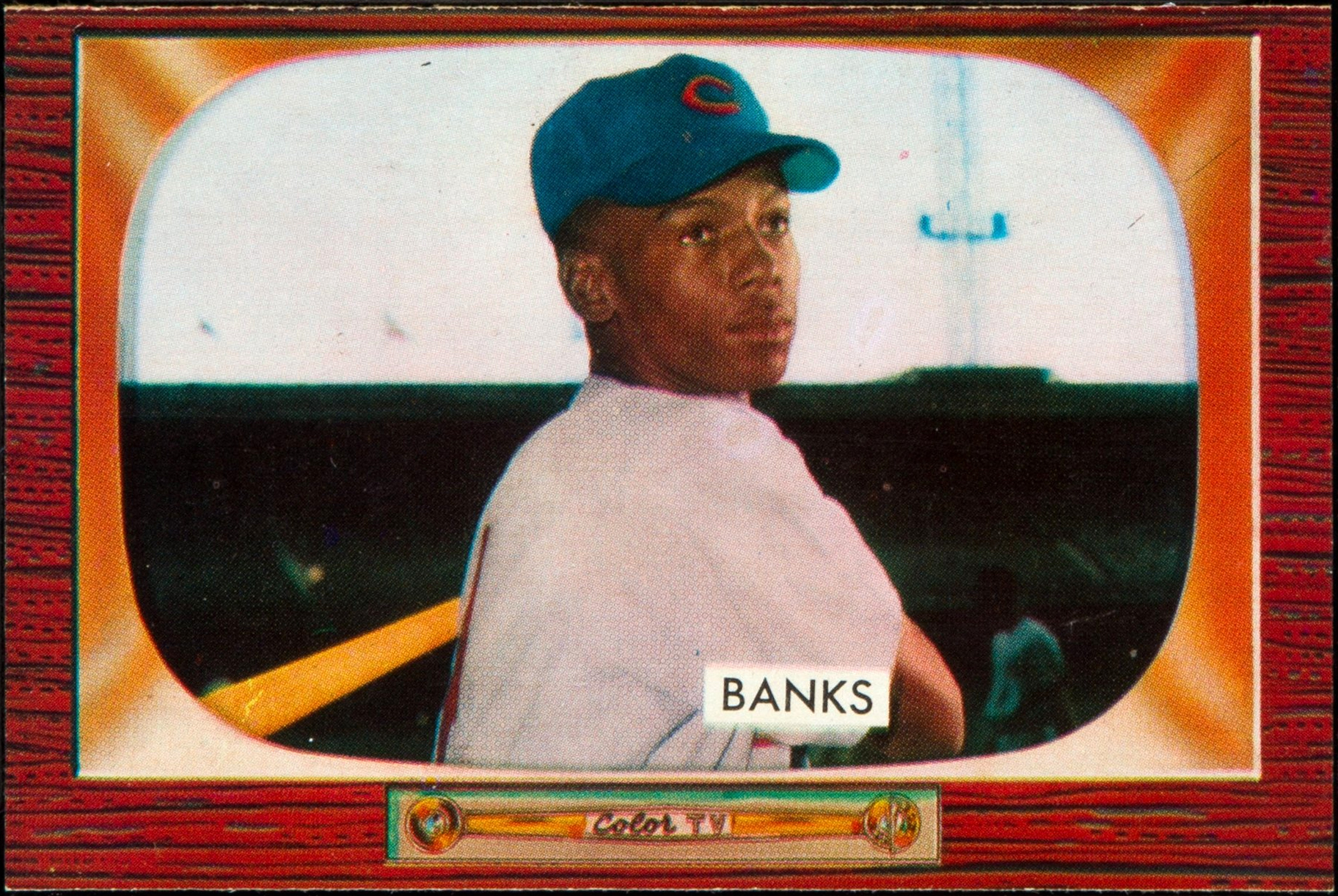

BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY Ernest "Ernie" Banks (born January 31, 1931), nicknamed "Mr. Cub" and "Mr. Sunshine", is a retired American professional baseball player. He was a Major League Baseball (MLB) shortstop and first baseman for 19 seasons, 1953 through 1971. He spent his entire MLB career with the Chicago Cubs. He was a National League (NL) All-Star for 11 seasons, playing in 14 All-Star Games.[1]

Banks was born and raised in Dallas. He entered Negro league baseball in 1950, playing for the Kansas City Monarchs. He served in the military for two years and returned to the Monarchs before beginning his major league career in September 1953. He made his first MLB All-Star Game appearance in 1955. Banks had his best seasons in 1958 and 1959, when he received back-to-back National League Most Valuable Player awards. In 1958, he hit .313 and led the NL with 47 home runs (HR) and 129 runs batted in (RBI). In 1959, he hit .304 with 45 HRs and led the NL with 143 RBIs.

During the 1961 season, Banks was transferred to left field followed by a final position change to first base. Cubs manager Leo Durocher became frustrated with Banks in the mid-1960's, saying that the slugger's performance was faltering, but he felt that he was unable to remove Banks from the lineup due to the star's popularity among Cubs fans. Banks was a player-coach from 1967 through 1971. In 1970, he hit his 500th career home run. In 1972, he joined the Cubs coaching staff after his retirement as a player.

Banks was active in the Chicago community during and after his tenure with the Cubs. He founded a charitable organization, became the first black Ford Motor Company dealer in the United States, and made an unsuccessful bid for a local political office. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977. In 1999, he was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. In 2013, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his contribution to sports. Banks lives in the Los Angeles area.

Early life

Banks was born in Dallas, Texas, to Eddie and Essie Banks on January 31, 1931.[2] He had eleven siblings, ten of them younger.[3]His father who had worked in construction and was a warehouse loader for a grocery chain, played baseball for black semi-pro teams in Texas.[2] As a child, Banks was not very interested in baseball, preferring swimming, basketball and football. His father bought him a baseball glove for less than three dollars at the local five and dime store. He bribed Banks with nickels and dimes to play catch.[4]Ernie's mother encouraged him to follow one of his grandfathers into a career as a minister.[5]

He graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in 1950.[6] While he was in high school which didn't have a baseball team, he played during the summer for a church softball team followed by the "Amarillo Colts" softball team; in school he lettered in basketball, football, and track.[7] History professor Timothy Gilfoyle wrote that Banks was discovered by Bill Blair, a family friend who scouted for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League[2] Other sources report that he was noticed by Cool Papa Bell of the Monarchs.[8][9]

In 1951, Banks was drafted into the US Army and served in Germany during the Korean War. He suffered a knee injury in basic training, but recovered after a few weeks of rest and therapy.[10] He served as a flag bearer in the 45th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion at Fort Bliss and while there he played with the Harlem Globetrotters on a part-time basis.[2] In 1953, he was discharged from the army and finished playing for the Monarchs that season with a .347 batting average.[8][11] Banks later said, "Playing for the Kansas City Monarchs was like my school, my learning, my world. It was my whole life."[9] In fact, when he was sold to the Chicago Cubs, Banks was reluctant to leave his Monarchs teammates.[9]

MLB career

Early career

Banks signed with the Cubs on September 14, 1953. He made his major league debut at Wrigley Field on September 17 at age 22, and played in ten games. He became one of a handful of former Negro league players who joined MLB teams without playing in the minor leagues.[8] He also was the first Cubs black player. In regard to Banks' view of race in baseball, authors Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt wrote that Banks "just was not the crusading type. He was so grateful to be playing baseball for a living, he did not have time to change the world, and if that meant some people called him an Uncle Tom, well, so be it. Banks was not about changing anyone's mind about the color of his skin; he was about baseball, pure and simple."[12]

He received a visit from Jackie Robinson during that first game he played that influenced his quiet presence in baseball. Robinson told Banks, "Ernie, I'm glad to see you're up here so now just listen and learn."[13] "For years, I didn't talk and learned a lot about people."[13]Over time when Banks felt like becoming more vocal, he discussed the issue with teammate Billy Williams, who advised him to remain quiet. Williams drew the analogy of fish that get caught once they open their mouths. "I kept my mouth shut but tried to make a difference. My whole life, I've just wanted to make people better", Banks said. (Chicago Tribune article, 2013)[13]

In 1954, Banks' double play partner during his official rookie season was Gene Baker, the second Cubs black player. Banks and Baker roomed together on road trips and became the first all-black double-play combination in major league history.[14] When Steve Bilko played first base, Cubs announcer Bert Wilson referred to the Banks-Baker-Bilko double play combination as "Bingo to Bango to Bilko".[15] Banks hit 19 home runs and finished second in Rookie of the Year voting.[16] Banks became a participant in a trend toward much lighter baseball bats after he accidentally picked up a teammate's bat and liked how easy it was to generate bat speed.[4]

In 1955, Banks hit 44 home runs, had 117 RBIs, and batted .295. He played in his first of 14 All-Star Games that season.[16] His home run total was a single-season record among shortstops.[17] He also set a thirty year record of five single-season grand slam home runs.[18] Banks finished third that year in the league's Most Valuable Player (MVP) voting.[19]The Cubs finished with a 72-81 win-loss record, winning only 29 of 77 road games.[20] In 1956, Banks missed 18 games due to a hand infection, breaking his 424 consecutive games played streak.[21] He finished the season with 28 home runs, 85 RBIs, and a .297 batting average. In 1957, he finished the season with 43 home runs, 102 RBIs, and a .285 batting average.[16]

Banks won the NL MVP Award in 1958 and 1959. He led the NL with 47 home runs in 1958 and was the league's RBI leader in both of those seasons. He became the first NL player to win the MVP award in back-to-back seasons.[22] In 1959, the Cubs came the closest to a winning season since Banks' arrival, finishing with a 74-80 record.[23] In 1960, Banks hit a league-leading 41 home runs, had 117 RBIs, and led the league in games played for the sixth time in seven years.[16] He also received the league's annual Gold Glove award for shortstop that year.

Joe Reichler, a writer for the Associated Press, reported on the eve of the 1960 World Series, that the Milwaukee Braves were prepared to pay cash and trade pitchers Joey Jay,Carlton Willey, and Don Nottebart, outfielder Billy Bruton, shortstop Johnny Logan, and first baseman Frank Torre in exchange for Banks from the Cubs.[24]

Move to first base

In 1961, Banks began having problems with his knee while playing shortstop when moving to his left or right side. It was the same knee he had injured while in the army. After playing in 717 consecutive games, he pulled himself from the Cubs lineup for at least four games, ending his pursuit of the NL consecutive games played streak (895 games) set by Stan Musial.[25] In May, the Cubs announced that Jerry Kindall would replace Banks at shortstop and that Banks would move to left field.[26] Banks later said, "Only a duck out of water could have shared my loneliness in left field."[27] Banks credited center fielder Richie Ashburn with helping him learn how to play left field; in 23 games he committed only one error. In June, he was moved to first base, learning that position from former first baseman and Cubs coach Charley Grimm.[28]

The Cubs began playing under the College of Coaches in 1961, a system in which decisions were made by a group of 12 coaches rather than by one manager.[29] By the 1962 season, Banks hoped to return to shortstop, but the College of Coaches had determined that he would remain at first base indefinitely.[30] In May 1962, Banks was hit in the head by a fastball from former Cubs pitcher Moe Drabowsky and was taken off the field unconscious.[31] He sustained a concussion on Friday, was in the hospital for two nights, sat out a Monday game, and hit three home runs and a double on Tuesday.[32]

In May 1963, Banks set a single-game record for putouts by a first baseman (22).[33] However, he caught the mumps that year and finished the season with 18 home runs, 64 RBIs, and a .227 batting average. Despite Banks' struggles that season, the Cubs managed to have their first winning record since the 1940s. Banks, following his doctor's orders, skipped his usual off season participation in handball and basketball and began the 1964 season weighing seven pounds more than the previous year. In February, Cubs second baseman Ken Hubbs, was killed in a plane crash.[34] Banks finished the season with 23 home runs, 95 RBI's, and a .264 batting average.[16] The Cubs finished in eighth place in 1964, losing over $315,000.[35] In 1965, Banks hit 28 home runs, had 107 RBI's, a .265 batting average, and played in the All-Star Game. On September 2, he hit his 400th home run.[16][36] The Cubs had finished the season with a baseball operations deficit of $1.2 million, though this was largely offset by television and radio revenue as well as the rental ofWrigley Field to the Chicago Bears football team.[37]

Leo Durocher was hired to be the Cubs manager in 1966. The Cubs hoped that Durocher could inspire renewed interest in the Chicago fan base.[38] Banks hit only 15 home runs and the Cubs finished the 1966 season in last place with a 59-103 win-loss record, the worst season of Durocher's career.[39] From the time that Durocher arrived in Chicago, he was frustrated at his inability to trade or bench the aging Banks. In Durocher's autobiography, the manager recalled that "he was a great player in his time. Unfortunately, his time wasn't my time. Even more unfortunately, there was not a thing I could do about it. He couldn't run, he couldn't field; toward the end, he couldn't even hit. There are some players who instinctively do the right thing on the base paths. Ernie had an unfailing instinct for doing the wrong thing. But I had to play him. Had to play the man or there would have been a revolution in the street."[40] Banks, on the other hand, said of Durocher, "I wish there had been someone around like him early in my career... He's made me go for that little extra needed to win."[41] Durocher served as Cubs manager until midway through 1972, the season after Banks retired.[16][42]

In Mr. Cub, a memoir published around the time that Banks retired, the slugger said that too much had been made of the racial implications in his relationship with Durocher and he summarized his thoughts on race relations:

My philosophy about race relations is that I'm the man and I'll set my own patterns in life. I don't rely on anyone else's opinions. I look at a man as a human being; I don't care about his color. Some people feel that because you are black you will never be treated fairly, and that you should voice your opinions, be militant about them. I don't feel this way. You can't convince a fool against his will... If a man doesn't like me because I'm black, that's fine. I'll just go elsewhere, but I'm not going to let him change my life.[43]

The Cubs named Banks a player-coach for the 1967 season. Banks competed with John Boccabella for a starting position at first base.[44] Shortly thereafter, Durocher named Banks the outright starter at first base.[45] Banks went to the All-Star Game, hit 23 home runs, and drove in 95 runs that year.[16] After the 1967 season, an article in Ebonypointed out that Banks had not been thought to make more than $65,000 (equal to $459,736 today) in any season. Banks had received a pay increase from $33,000 to $50,000 between his MVP seasons in 1958 and 1959, but Ebony reported that several MLB players were making $100,000 at the time.[3]

Final seasons

Banks won the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award in 1968, an honor recognizing playing ability and personal character.[46] The 37-year-old Banks hit 32 home runs, had 83 RBI's, and finished that season with a .246 batting average.[16] In 1969, Banks came the closest to helping the Cubs win the National League pennant; the Cubs fell out of first place after holding an 81⁄2 game lead in August.[47] Banks made his eleventh and final All-Star Game appearance that season (2 games were played 1959 through 1962).[16] Banks hit his 500th home run on May 12, 1970 at Chicago's Wrigley Field[36] On December 1, 1971, Banks retired as a player but continued to coach for the Cubs until 1973. He was an instructor in the minor leagues for the next three seasons and also worked in the Cubs front office.[48]

Banks finished his career with 512 home runs, and his 277 home runs as a shortstop were a career record at the time of his retirement. (Cal Ripken, Jr now holds the record for most home runs as a shortstop with 345.[49]) Banks holds Cubs records for games played (2,528), at-bats (9,421), extra-base hits (1,009), and total bases (4,706).[50] Banks excelled as an infielder as well. He won a National League Gold Glove Award for shortstop in 1960. He led the NL in putouts five times and was the NL leader in fielding percentage as shortstop three times and once as first baseman.[16]

Banks holds the major league record for most games played without a postseason appearance (2,528).[51] In his memoir, citing his fondness for the Cubs and owner Philip K. Wrigley, he said that he did not regret signing with the Cubs rather than one of the more successful baseball franchises.[52] Banks's popularity and positive attitude led to the nicknames "Mr. Cub" and "Mr. Sunshine".[53][54] Banks was known for his catchphrase, "It's a beautiful day for a ballgame... Let's play two!", expressing his wish to play a double header every day out of his pure love for the game of baseball.[53]

Personal life

Banks married his first wife Mollye Ector in 1953. He had proposed to her in a letter from Germany and they married when he returned to the US.[55] He filed for divorce two years later. The couple briefly reconciled in early 1959.[56] By that summer, they agreed on a divorce settlement that would pay $65,000 to Ector in lieu of alimony.[57] Shortly thereafter, Banks eloped with Eloyce Johnson. Within a year, the couple had twin sons. They had a daughter four years after that.[58]

Banks ran for alderman in Chicago in 1962. He lost the election and later said, "People knew me only as a baseball player. They didn't think I qualified as a government official and no matter what I did I couldn't change my image... What I learned, was that it was going to be hard for me to disengage myself from my baseball life and I would have to compensate for it after my playing days were over."[59] Ector filed suit against Ernie in 1963 for failing to make payments on a life insurance policy as agreed upon in their divorce settlement.[60]

In 1966, Banks worked for Seaway National Bank in the offseason and enrolled in a banking correspondence course.[3] He also bought into several business ventures during his playing career, including a gas station.[3] Though he had been paid modestly in comparison to other baseball stars, Banks had taken the advice of Wrigley and invested much of his earnings. He later spent time working for an insurance company and for New World Van Lines. Banks began building assets that would be worth an estimated $4 million by the time he was 55 years old.[43]

Banks and Bob Nelson became the first black owners of a U.S. Ford Motor Company dealership in 1967. Nelson had been the first non-white commissioned officer in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II; he operated an import car dealership before the venture with Banks.[61] Banks was appointed to the board of directors of the Chicago Transit Authority in 1969.[62] On a trip to Europe, Banks was able to visit the Pope, who presented him with a medal that became a proud possession.[3]

Banks was divorced from Eloyce in 1981. She received several valuable items from his playing career as part of their divorce settlement, including his 500th home run ball. She sold the items not long after the divorce.[63] In 1984, he married a woman named Marjorie.[64] In 1993, Marjorie was part of group that met with MLB executives about race relations in baseball after allegations of racial slurs surfaced against Cincinnati Reds owner Marge Schott.[65] Banks married Liz Ellzey in 1997 and Hank Aaron served as his best man.[66] In late 2008, Banks and Ellzey adopted an infant daughter.[67]

Banks's nephew, Bob Johnson, was a major league catcher and first baseman for the Texas Rangers between 1981 and 1983.[68] His great nephew, Acie Law, is a professional basketball player who attended Texas A&M University before playing in the National Basketball Association (NBA).[69]

Later years

Banks was voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977, his first year of eligibility.[70] He received votes on 321 of the 383 ballots.[16] Though several players were selected through the Veterans Committee and the Committee on Negro Baseball Leagues that year, Banks was the only player elected by the Baseball Writers' Association of America. He was inducted on August 8 of that year. During his induction speech, Banks said, "We've got the setting - sunshine, fresh air, the team behind us. So let's play two!"[71]

The Cubs retired Banks's uniform number 14 in 1982.[50] He was the first player to have his number retired by the team.[72] He was employed as the corporate sales representative for the Cubs at the time of the ceremony.[73] No other numbers were retired by the team for another five years, when Billy Williams received the honor. Through the 2013 season, only six former Cubs have had their numbers retired.[74]

Banks has served as a team ambassador since his retirement, though author Phil Rogers points out that the team has never placed Banks in a position of authority or significant influence.[75] In 1983, shortly after Wrigley sold the team to the Tribune Company, Banks and the Cubs briefly severed ties. Rogers wrote that Banks was viewed as "something of a crazy uncle who hung around the house for no apparent reason"[75] after the sale. Rogers says that team officials anonymously told the press that Banks was fired because he was unreliable. Soon Banks and the Cubs reconciled and the former shortstop began making appearances on behalf of the Cubs again.[75]

When the 1984 Cubs won the NL East division, the club named Banks an honorary team member.[76] At the 1990 Major League Baseball All-Star Game, the first one held atWrigley Field since Banks' playing days, he threw out the ceremonial first pitch to starting catcher Mike Scioscia.[77] He was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team in 1999.[78] In the same year, the Society for American Baseball Research listed him 27th on a list of the 100 greatest baseball players.[79]

In June 2006, Crain's Chicago Business reported that Banks was part of a group looking into buying the Chicago Cubs, in case the Tribune Company decided to sell the club.[80]Banks established a charity, the Live Above & Beyond Foundation which assists youth and the elderly with self-esteem, healthcare and other opportunities.[81] In 2008, Banks released a charity wine called Ernie Banks 512 Chardonnay; all of its proceeds are donated to his foundation.[82] Banks is an ordained minister and he presided at the wedding of MLB pitcher Sean Marshall.[83]

On March 31, 2008, a statue of Banks ("Mr. Cub") was unveiled outside Wrigley Field.[84] That same year, Eddie Vedder released the song "All The Way"; Banks had asked Vedder to write a song about the Cubs as a birthday gift.[85] In 2009, Banks was named a Library of Congress Living Legend, a designation that recognizes those "who have made significant contributions to America's diverse cultural, scientific and social heritage."[86] On August 8, 2013, he was announced as a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[87] Banks was honored with 15 other people, including Bill Clinton and Oprah Winfrey. He said that he presented President Obama with a bat that had belonged to Jackie Robinson.[88]

Banks remains close to the Cubs and makes frequent appearances at the team's spring training grounds, Ho Ho Kam Stadium in Arizona. Author Harry Strong wrote in 2013 that "the Chicago Cubs do not have a mascot, but they hardly need one when the face of the franchise is still so visible."[89]

No comments:

Post a Comment