BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY

James Bevel

| James Bevel | |

|---|---|

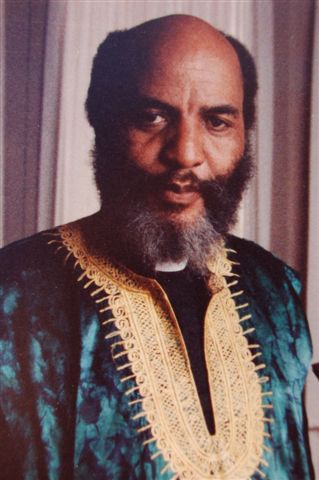

Bevel in the 1980s

| |

| Born | James Luther Bevel October 19, 1936 Itta Bena, Mississippi |

| Died | December 19, 2008 (aged 72) Springfield, Virginia |

| Occupation | Nonviolent scientist, SCLCDirector of Direct Action |

| Known for | Strategist of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, Selma Voting Rights Movement, Birmingham Children's Crusade, Selma to Montgomery march, andChicago Open Housing Movement |

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was a leader of the 1960's Civil Rights Movement who, as the Director of Direct Action and Director of Nonviolent Education of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) initiated, strategized, directed, and developed SCLC's three major successes of the era:[1][2] the 1963 Birmingham Children's Crusade, the1965 Selma Voting Rights Movement, and the 1966 Chicago Open Housing Movement.[3] Rev. Bevel also called for and initially organized the 1963 March on Washington[4] and initiated and strategized the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, which, in addition to Bevel's Birmingham Children's Crusade, were SCLC's main public gatherings of the era. For Bevel's work in the 1960s he has been referred to as the "Father of Voting Rights",[5] the "Strategist and Architect of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement",[6] and as half of the Bevel/King first-tier team that formulated and communicated the actions, issues, and dialogues which created the historical changes of the 1960s civil rights era.[7][8]

Prior to his time with SCLC, Bevel worked in the Nashville Student Movement, where he participated in the 1960 Nashville Lunch-Counter Sit-Ins, directed the 1961 Open Theater Movement, chose the riders for the 1961 Nashville Student Movement continuation of the Freedom Rides, and initiated and directed the Mississippi Voting Rights Movement in 1961 and '62. Later, in 1967, Bevel took a leave from SCLC to direct the Anti-Vietnam War Movement when he was named the leader of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam where he initiated and called the 1967 March on the United Nations.[7][8] His last major action was as co-initiator of the 1995 Day of Atonement/Million Man March.

In 2005 Bevel was accused of incest by one of his daughters. He went to trial in April, 2008 and, although he denied the charge, Bevel was convicted of unlawful fornication and sentenced to 15 years in prison and fined $50,000. After serving seven months he was freed awaiting an appeal, and died of pancreatic cancer in December 2008. He was buried in a 17-foot canoe in a small country cemetery in Eutaw, Alabama.

Early life and education

Born in Itta Bena, Mississippi, Bevel grew up and worked on a cotton plantation, received schooling in Mississippi and Cleveland, Ohio, and served in the U.S. Navy for a time. He attended the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee from 1957 to 1961,[9] and while attending college re-read Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God is Within You (he'd first read it while in the Navy, where the book led directly to Bevel's decision to leave the military). Bevel also read several of Mohandas Gandhi's books and newspapers while taking workshops on Gandhi's philosophy and nonviolent techniques taught off-campus by Rev. James Lawson of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Bevel also had attended workshops at the Highlander Folk School taught by its founder, Myles Horton.

Nashville Student Movement, SNCC

In 1960, along with several of James Lawson's and Myles Horton's other students — Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash and others — Bevel participated in the 1960 Nashville Sit-In Movement which desegregated the city's lunch counters. After the success of this early movement action, and with the aid of SCLC's Ella Baker, activist students from Nashville and across the South developed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). James Bevel, working on SNCC's commitment to desegregate theaters, successfully strategized and directed the 1961 Nashville Open Theater Movement.

Right after the Open Theater Movement's success in Nashville - the only city in the country which had actually organized an action - the Nashville Student Movement's chairman, Diane Nash, told the group that they must continue the 1961 Freedom Rides when its organizers - The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) - called off the Ride after a bus was firebombed in Birmingham. James Bevel was put in charge of choosing which students would go on which bus. Bevel and the others were then arrested when they arrived in Jackson, Mississippi and tried to desegregate the waiting rooms.

While in the Jackson jail, Bevel and Lafayette initiated the Mississippi Voting Rights Movement. They, Nash, and others stayed in Mississippi to work on what soon became known as the Mississippi Freedom Movement.

Earlier, Lafayette and his wife, Colia Lidell, had opened a SNCC project in Selma, Alabama to assist the work of local organizers like Amelia Boynton.

1962 Bevel/King Agreement

In 1962, after several successful years working on and organizing within the Nashville Student Movement and working in the Mississippi Movement, James Bevel was invited to meet with Martin Luther King, Jr. in Atlanta.[7][8] At that meeting, which had been suggested by James Lawson,[8] Bevel and King agreed to work together on an equal basis, with neither having veto power over the other, on projects under the auspices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). They agreed that they would work without compromise until they had ended segregation, had obtained voting rights, and assured that all American children had a quality education.[7][8] They agreed to not stop until these steps occurred, and also to ask for funding for SCLC only if the group was involved in organizing a movement.[7][8]

Bevel soon became SCLC's Director of Direct Action and Director of Nonviolent Education to augment Dr. King's positions as SCLC's chairman and spokesperson.

1963 Birmingham Children's Crusade and its planned March on Washington

In 1963, after SCLC agreed to assist one of its founders, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, and others in their work on a movement in Birmingham, Alabama. After the demonstrations resulted in Dr. King, Ralph Abernathy, and Fred Shuttlesworth being arrested and jailed while marching, James Bevel came up with the idea of using children in the campaign. He spent weeks strategizing, organizing and educating Birmingham's elementary and high school students in the philosophy and techniques of nonviolence. Bevel then directed the students, 50 at a time, to march out of Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church and walk to Birmingham's City Hall to talk to Birmingham Mayor Art Hanes about segregation in the city. Almost 1,000 of them were arrested the first day. When they continued marching out of the church the following day, City Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene "Bull" Connor ordered that German Shepherd dogs and high-pressure fire hoses be used on the children. This action culminated in international public outrage over the cities use of force to stop nonviolent children from marching to Birmingham's City Hall.

During the Birmingham Children's Crusade, President John F. Kennedy asked Dr. King to stop involving children in the campaign. King told Bevel to not use the students anymore, but instead, Bevel told King he would not stop the action but would now organize the children to march to Washington D.C. to meet with Kennedy about segregation. King agreed.[4] Bevel then went directly to the children, and asked them to prepare to take to the highways on a march to Washington to question Kennedy about correcting the problem of segregation in America.[4] The Kennedy administration, hearing of this plan, asked SCLC's leaders what they would want to see in a comprehensive civil rights bill, which was then written by the Kennedy administration and agreed to by SCLC's leadership, thus ending the need for the children of Birmingham to take to the highways and march to Washington.

Shortly thereafter, in August 1963, SCLC participated in what has become known as the March on Washington, an event organized by labor leader A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, who'd been the original planners (with A. J. Muste) of the 1941 March on Washington. Just as the "threat" of the children marching along the highway from Birmingham to Washington led directly to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the threat of the 1941 march led President Franklin Roosevelt to sign the Fair Employment Act, and neither march was actually held.

The Alabama Project and the 1965 Selma Voting Rights Movement

Weeks after the March On Washington, in September 1963, a bomb at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham killed four young girls attending Sunday School. Bevel responded by proposing the Alabama Voting Rights Project, co-wrote the project proposal with his then wife, Diane Nash, and they soon moved to Alabama and began to implement the Alabama project along with Birmingham student activist James Orange.

Starting in late 1963 Bevel, Nash, and Orange organized the voting rights movement in Alabama until, in late 1964, Dr. King and the rest of SCLC came to Selma to work alongside Bevel's and Nash's Alabama Project[3] and SNCC's Voting Rights Project (headed at that time by Prathia Hall and Worth Long). The Bevel/Nash Alabama Project and its SNCC counterpart then became collectively known as the Selma Voting Rights Movement, with James Bevel as its director.

The Selma Voting Rights Movement officially began in early January 1965, grew, and had some minor successes. Then, on February 16, 1965, a young man, Jimmie Lee Jackson, went with his mother and grandfather to participate in a nighttime march led by Reverend C. T. Vivian to protest the movement related jailing of James Orange in Marion, Alabama. After the street lights were turned off by Alabama State Troopers, Jackson was shot in the stomach while defending his mother from an attack by the Troopers as she in turn was defending her father. Jackson died a few days later.

When Bevel heard of Jackson's impending death he walked around outside Selma's Torch Motel until a strategy to redirect the anger of the citizens of Marion and Selma came to him, and after Jackson died he called for a march from Selma to Montgomery to talk to Governor George Wallace about the attack in which Jackson was shot.[8] As the first march reached the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge a large group of marchers — including SNCC Chairman John Lewis and Amelia Boynton — were bludgeoned and tear-gassed in what became known as "Bloody Sunday".

After a court order by Judge Frank Johnson cleared the way for the march to continue, hundreds of religious, labor and civic leaders, many celebrities, and activists and citizens walked the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery. Before this final march occurred, President Lyndon Johnson had gone on national television to address a joint session ofCongress and demanded that it pass a comprehensive Voting Rights Act.

Because of the unprecedented success of their 1963-1965 Alabama Project, in 1965 SCLC gave its highest honor — the Rosa Parks Award — to James Bevel and Diane Nash.

The 1966 Chicago Open Housing Movement and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement

In 1966, Bevel chose Chicago as the site of SCLC's long-awaited Northern Campaign.[10] There he at first worked on "ending" slums and creating tenant unions. He then decided on the main theme of the action: from previous discussions and agreements with Dr. King, and from the ideas and work of American Friends Service Committee activist Bill Moyer, Bevel strategized, organized, and directed the Chicago Open Housing Movement. This movement ended within a Summit Conference which included Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley.

As the Chicago movement neared its conclusion A. J. Muste, David Dellinger, representatives of North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh, and others asked Rev. Bevel to take over the directorship of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.[11] After researching the war, and after getting Dr. King's agreement to work with him on this project, Bevel agreed to lead the antiwar effort. He renamed the organization the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, brought many diverse groups into the movement, and strategized and organized the April 15, 1967 march from Central Park to the United Nations Building. Originally planned as a rally in Central Park, the United Nations Anti-Vietnam War March became the largest demonstration in American history to that date. During his speech to the crowd that day, Bevel called for a larger march in Washington D.C., a plan that evolved into the October 1967 March on the Pentagon, a large rally attended by many hippie peace activists who followed the growing counter culture movement.[12]

Dr. King's assassination

Rev. Bevel, who witnessed King's assassination on April 4, 1968, reminded SCLC's executive board and staff that evening that Dr. King had left "marching orders" that, if anything should happen to him, Rev. Ralph Abernathy should take his place as SCLC's Chairman.[13] Bevel opposed SCLC's next action, the 1968 Poor People's Campaign, but in order to handle any problems which may have occurred he took on the role of its Director of Nonviolent Education.

1984 Congressional bid

Bevel ran and lost as the Republican candidate for Illinois' 7th Congressional District in 1984.

Moon and LaRouche involvements

In 1989 Bevel, together with Ralph Abernathy, organized the National Committee Against Religious Bigotry and Racism, a group backed by the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon.[14][15] Bevel denounced the deprogramming of a Moon follower as reminiscent of the "pre-civil rights mentality" and called for the protection of religious rights.[16] In 1987 Bevel had taken part in a public protest against the Chicago Tribune because of that newspaper's use of the word "Moonies" when referring to Unification Church members. Bevel handed out fliers at the protest which said: "Are the Moonies our new niggers?"[17]

Bevel moved to Omaha, Nebraska, in November 1990 as the leader of the "Citizens Fact-Finding Commission to Investigate Human Rights Violations of Children in Nebraska", a group organized by the Schiller Institute.[18] The group, associated with economist and conspiracy theorist Lyndon LaRouche, distributed petitions seeking to reopen the state legislature's two-year investigation into the Franklin child prostitution ring allegations. Bevel never submitted the collected petitions and left the state the following summer.[19] In 1992, Bevel ran as the vice presidential candidate on LaRouche's ticket while that perennial candidate was serving a prison sentence for mail fraud and tax evasion.[20] He engaged in LaRouche seminars on issues like "Is the Anti Defamation League the new KKK?"[21] When he introduced LaRouche to a convention of the National African American Leadership Summit in 1996, both men were booed off the stage and a fight broke out between LaRouche supporters and black nationalists.[22]

1995 Day of Atonement/Million Man March

Louis Farrakhan credits Bevel with helping to formulate the 1995 Day of Atonement/Million Man March in Washington, D.C.[23] Its main sponsor was the Nation of Islam.[24]

Criminal charges

In May 2007, Bevel was arrested in Alabama on charges of incest committed sometime between October 1992 and October 1994 in Loudoun County, Virginia. Bevel was living in Leesburg, Virginia, at the time and working with La Rouche's group, whose international headquarters was a few blocks from Bevel's apartment.

The accuser, one of his daughters, was 13–15 years old at the time, and lived with him in the Leesburg apartment. Three of his other daughters have also alleged that Bevel sexually abused them, although not with intercourse. Charged with one count of unlawful fornication in Virginia, which has no statute of limitations for incest, Bevel pleaded innocent and continued to deny the main accusation. His four-day trial in April 2008 included "testimony about Bevel's philosophies for eradicating lust, and parents' duties to sexually orient their children". During the trial, the accusing daughter testified that she was repeatedly molested beginning when she was six years old.[25][26][27]

During the trial, prosecutors used as key evidence against Bevel a 2005 police-sting telephone call recorded by the Leesburg, Virginia police without his knowledge.[28] During that 90-minute call, Bevel's daughter asked him why he had sex with her the one time in 1993, and she asked him why he wanted her to use a vaginal douche afterward.[28]Bevel's response to his daughter was that he had no interest in getting her pregnant.[28] Bevel's statement was used against him during the trial after he denied committing the sexual act.[28]

On April 10, 2008, after a three-hour deliberation, the jury found Bevel guilty, his bond was revoked, and he was taken into custody.[29] The judge sentenced him on October 15, 2008, to 15 years in prison and fined him $50,000. After the verdict, Bevel claimed that the charges were part of a conspiracy to destroy his reputation, and said that he mightappeal. He received an appeal bond on November 4, 2008, and was released from jail three days later, six weeks before his death from pancreatic cancer, at age 72, in a hospice home in Springfield, Virginia, manned by his wife Erica and his daughter Sherri.[citation needed]

Bevel's attorney requested that the Court of Appeals of Virginia abate the conviction (effectively clearing Bevel's name) on account of his death. The Court of Appeals remanded the case to the trial court to determine whether there was good cause not to abate the conviction. The trial court found that abating the conviction would deny the victim the closure that she sought and denied the motion to abate. The Court of Appeals affirmed this judgment. Bevel's attorney appealed the denial of the abatement motion to theSupreme Court of Virginia. In an opinion issued November 4, 2011, the Supreme Court held that abatement of criminal convictions was not available in Virginia under the circumstances of Bevel's case and, because the executor of Bevel's estate had not sought to prosecute the appeal, the Court affirmed the conviction.[30]

No comments:

Post a Comment