BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY "Deemed Unsuitable" ”: Black Pioneers in Western Canada

On August 12, 1911 the Laurier government drafted and approved a remarkable document.

On August 12, 1911 the Laurier government drafted and approved a remarkable document. The proposed Order in Council read:

For a period of one year from and after the date hereof the landing in Canada shall be [sic] and the same is prohibited of any immigrants belonging to the Negro race, which race is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.

|

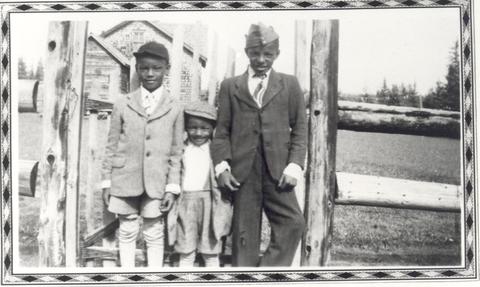

| Thomas Mapp and family, a group of Black settlers from Amber Valley, Alberta (courtesy Glenbow Archives/NA-316.1). |

The fact that the government of Canada preferred some immigrants to others was scarcely surprising in 1911. Although not officially ranked by preference, people from Great Britain and northern Europe were favoured, with other Europeans somewhat lower on the list, and Asians of all nationalities lower still. Surprisingly the government hoped to keep some American citizens from entering Canada, while encouraging most others to come. In the end, this Order in Council was never invoked, but the story of how Black Americans came to be deemed "unsuitable" as settlers is fascinating, and disturbing.

There had been Black settlers in western Canada prior to 1905, but they were few in number and most attracted little notice. However, in the early 1900s larger numbers of Black settlers were attracted by a combination of the promotional literature extolling ours as the "Last, Best West," and growing political and economic discrimination in a number of American states, particularly Oklahoma.

Between about 1905 and 1911 over one thousand Black Americans emigrated to western Canada, and thousands more might have come had Canada proved more welcoming. By 1908-09 there were small communities of Black homesteaders at Wildwood, Alberta and near Maidstone, Saskatchewan. Over the next two years a small settlement was established at Campsie, near Barrhead, Alberta, and larger settlements at Breton and Amber Valley, just east of Athabasca, Alberta. Not all found the prospect of homesteading in the bush attractive, and some chose to stay in cities to find work. Edmonton, in particular, attracted a significant number, and by 1910 it was reported that as many as 100 Blacks were living there.

This increasingly visible minority and reports of large parties of Black settlers preparing to come to Canada caused an uproar. The Edmonton Board of Trade led the way, and in 1910 it stated, "We want settlers that will assimilate with the Canadian people and in the negro we have a settler that will never do that." Canadian immigration authorities agreed. Attempts were made to keep Blacks from obtaining immigration literature, and plans were made to use medical inspections and other deterrents to keep Blacks from entering Canada.

One group attracted close attention. Its leader, Henry Sneed, had visited western Canada in 1910 to scout land before returning to Oklahoma to recruit settlers. By early 1911 Sneed and a party of 194 men, women and children were ready to leave for Canada. A second group of about 200 people waited behind to see what would happen when the first reached Canada.

Once in Canada, their progress became the subject of extensive newspaper commentary. In Edmonton, the Board of Trade resumed its leadership role in opposing Black settlement, but now it was supported by other organizations ranging from the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) to the Edmonton Trades and Labour Council. The Board of Trade prepared a petition addressed to Prime Minister Laurier, which was posted prominently in a number of Edmonton area businesses and taken door to door by canvassers. Despite having a total population of just 25 000 people at the time, some 3000 Edmontonians signed. The petition read in part:

We, the undersigned residents of the City of Edmonton, respectfully urge upon your attention and that of the Government of which you are the head, the serious menace to the future welfare of a large portion of western Canada, by reason of the alarming influx of Negro settlers.

The Laurier government was vulnerable on this issue, especially as Frank Oliver was both Minister of the Interior - and thus responsible for immigration policy - and the Member of Parliament for Edmonton. The infamous Order in Council was quickly drawn up. Government immigration agents also followed a less direct approach to the issue. They made a concerted effort to convince potential Black settlers that western Canada was not really the "Last, Best West" - at least not for them.

In the end, this campaign and a growing sense on the part of Black community leaders that emigration was not the answer, slowed Black immigration. The government was able to congratulate itself that the crisis had been averted. But for one brief moment, the intolerant face of Canadian society had been starkly revealed.

In the end, most Black settlers made the best of their new homes, despite the poor reception they initially received. Many have made significant contributions in politics, the arts, sports and other fields. In 1986, for example, many Canadians were probably puzzled over how a remarkable athlete named Reuben Mayes could be the National Football League's Rookie of Year and yet come from North Battleford. Like so many other settlers and their descendants who went on to successful careers, he was just one part of this "unsuitable" aspect of Canadian history.

No comments:

Post a Comment