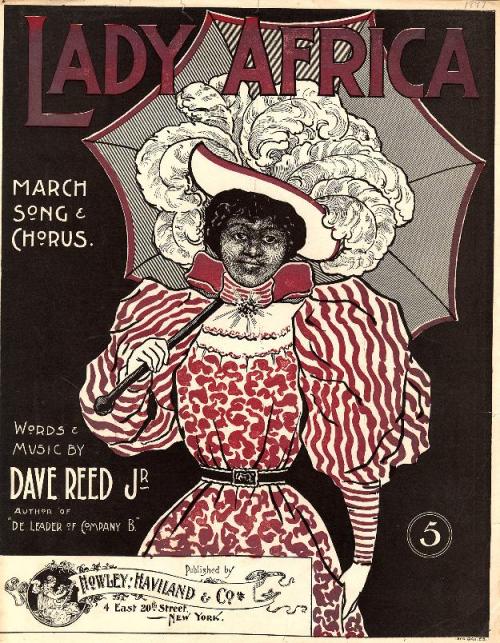

Lady Africa

Lady Africa

Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University (Durham, North Carolina)

Title of Song: Lady Africa

Composer: Reed Jr., Dave

Illustrator: Davies

Publisher: Howley, Haviland & Dresser

Year & Place: 1897; New York, New York

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music B-807

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: hasm.b0807

Basic Description

This is a multi-colored portrait of a slender woman sporting an umbrella, a hat and gloves. The frame only allows the viewer to see three-quarters of her body. Her hat features large, undulating feathers that seem to spring out of the hat like volutes. While the fabric of her sleeves hugs her wrists and forearms, it expands exponentially in a balloon-like fashion from her forearms to her shoulders. The sleeves in this area are unsually large, approximating the width of her entire body. This contrasts with the woman’s collar, which is wrapped tightly around her neck and is tied in a bow just below the nape of her neck with a broad, dark magenta ribbon. It is her right hand that holds the umbrella in balance over her shoulders. The dress is made of a printed fabric comprised of stripes in the sleeves and swirls reminiscent of an arabesque decoration in the bodice. Additionally, the bodice is cinched at the waist and a brooch is pinned to the front of her neck.

Personal Description

This image seems to attempt to reference feminine, middle-class respectability and propriety as evidenced by the body’s lavish decoration and formal attire. The main elements or accoutrements such as the gloves, hat and umbrella are signifiers of a historically specific type of formality. It is difficult to understand if this image takes steps towards caricature or of it it can be understood a serious representation of an individual. This referencing of civil society does not seem completely out of line with what the actual social and stylistic demands of the day might have been. There are few things that are odd such as the lack of visual context or background that would help the reader better identify her. It is also striking that she wears both the hat and the umbrella as one would seem to counter the need for the other. What may be most striking is the formality’s combination with a black body. The title of this piece, “Lady Africa” offers few clues that help in constructing an interpretation. The reference to Africa itself, however, does suggest that what the viewer sees here, a female of African-descent attempting to ascend to “lady-hood” might have been a humorous spectacle for turn of the century viewers, in much the same way that viewing markers of indigenous culture might have been. Still, it seems that there is an inaccessible aspect of this piece, which needs a late-nineteenth century audience to be activated.

Reality Check

Untitled, Missouri State Archives, circa 1890’s

This image from the Missouri State Archive depicts an woman (anonymous) wearing a long dress with lace embroidery.

Source:

Shaw, Gwendolyn DuBois., and Emily K. Shubert. Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century. Andover: Addison Gallery of American Art Phillips Academy, 2006.

Leave a comment

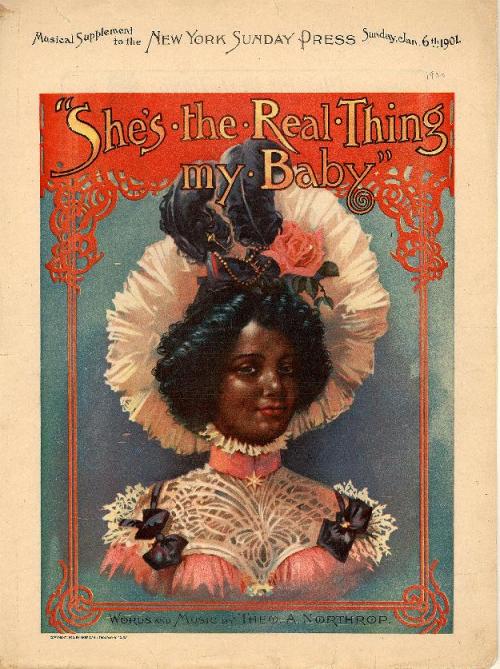

“She’s the Real Thing my Baby”

Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University (Durham, North Carolina)

Title of Song: She’s The Real Thing My Baby

Composer: Northrop, Theo A.

Illustrator: American Lithographic

Publisher: New York Sunday Press

Year & Place: 1901; New York, New York

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music B-0411

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: hasm.b0411

Basic Description

This portrait of an African-American female framed with thick red lines depicts her embellished body from her head to the beginning of her chest. Covered in a pink and white lace dress, a full head of ebony black curls frame her face and a large white hat with two black feather sits at the crown of her head. Her pink and white collar is wrapped tightly around her neck as she turns her head slightly while gazing out towards the viewer. With a slight shine, her soft, supple skin gleams in the light.

Personal Description

Loudly announcing that this female subject is the real thing, this lithograph paradoxically exhibits an abundance of artifice. The woman looks as though her collar might cut off the circulation of air through her trachea while the treatment of her skin renders her a Mattel plastic product. The only part of her body left without some degree of adornment is her face. Even this, however, displays ambiguity with its Mona Lisa-esque smile in which it is not clearly smiling or grimacing bitterly. And all of this ambiguity begs the question: Is Theo Northrop’s ‘baby’ really real, a figment of the author’s imagination, or a combination of both?

Reality Check

Born and educated in Richmond, Virginia, Adah Belle Samuels Thoms championed equal opportunity for African-American women first as a teacher in Virginia and later during her professional nursing career. A graduate of the Lincoln Hospital’s School of Nursing – the first in the nation to train black women as nurses when it started with six students in 1898 – she was the President of the Lincoln Hospital Alumnae Association in New York.

Samuels Thoms was the charter member for and hosted the organizational meeting of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses in New York City. The American Nurses Association had a whites-only policy. In August of 1908, fifty-two nurses gathered at St. Marks Episcopal Church to found the new group for Colored Graduate Nurses.

Thoms campaigned for the enrollment of black nurses by the American Red Cross during World War I and was influential in increasing the number of African-American nurses in public health nursing positions. Later on in life she wrote Pathfinders, the first history of African-American nurses.

(Source: Dodson, Howard, Christopher Paul. Moore, and Roberta Yancy. The Black New Yorkers: The Schomburg Illustrated Chronology. New York: John Wiley, 2000)

Kemo, Kimo

Location: American Song Sheets Collection, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Title of Song: Kemo, Kimo

Publisher: J.H. Johnson

Year & Place: circa 1854, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Collection/Call Number: American Song Sheets, Broadsides, Box 2, bsvg200815

American Song Sheets Item #: bsvg200815

Basic Description

The engraving at the head of this broadside is of a woman, who wears a tall bonnet decorated with multiple bows, and a dress with puffy sleeves and a tight-fitting, lace-up bodice. Seated on a low bench, the woman turns her upper body to the right while strumming on a guitar.

Personal Description

The engraver’s rendering is derived from stock illustrations in the antebellum period of an ostentatious African American woman: a characterization which appeared on selected broadsides and sheet music covers in New York and Philadelphia beginning in the 1840s. A female counterpart to the Zip Coons and other male dandy personas in blackface minstrelsy, this woman’s indiscretions are literally enmeshed within her fancy ribbons, lacework, and bows.

Reality Check

Elizabeth Brown Montier (1820-ca. 1858)

Little is known of Elizabeth Brown Montier, apart from her being married, circa 1841, to Philadelphia bootmaker Hiram Montier, a direct descendant of Philadelphia’s first mayor, Richard Morrey. The couple lived in the city’s Northern Liberties neighborhood, and Montier’s shop was on NW 7th Street. This portrait, along with a companion portrait of Hiram Montier, was painted by Philadelphia artist Franklin R. Street, and may have been created on the occasion of the couple’s marriage.

Ma Daffodil

Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Title of Song: Ma Daffodil

Composer: Know, Paul J and Marion, Harry S.

Publisher: T.B. Harms & Company

Year & Place: 1900, New York, NY

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music B-872

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: hasm.b0872

Basic Description

The bust of a stylishly dressed woman, flanked by a half-a-dozen or so large, daffodil-like flowers, comprises this two color (yellow and purple) lithograph. The rendering itself is highly stylized, reminiscent of Art Nouveau, which is exemplified in the wallpaper-like daffodil design, the flat, graphic treatment of the woman’s coat, and her naturalisticly drawn face and abundant hair and hat. She smiles in a soft, simple manner, and her face exudes an attractive, inviting demeanor.

Personal Description

What’s especially intriguing about this image is the artist’s incorporation of this African American woman into a glamorous, Art Nouveau (re: modern) mode. With absolutely no traces whatsoever of the period’s stereotypic portrayals of black people in American commercial design and advertising, Ma Daffodil links this particular African American woman with the classic symbols of beauty (re: flowers, high fashion, and moderation in facial features) and the possibilities of representing aesthetic sophistication.

Reality Check

Aida Overton Walker (1880-1914)

Born in 1880 in Richmond, Virginia, Aida Overton grew up in New York City, where her family moved when she was young and where she gained an education and musical training. At fifteen, she joined John Isham’s Octoroons, one of the most influential black touring groups of the 1890s, and the following year she became a member of the Black Patti Troubadours. In 1898, she joined the company of the famous comedy team Bert Williams and George Walker, and appeared in all of their shows—The Policy Players (1899), The Sons of Ham(1900), In Dahomey (1902), Abyssinia (1905), and Bandanna Land (1907). Within about a year of their meeting, George Walker and Overton married and before long became one of the most admired and elegant African American couples on the stage.

While George Walker supplied most of the ideas for the musical comedies and Bert Williams enjoyed fame as the “funniest man in America,” Aida quickly became an indispensable member of the Williams and Walker Company. Onstage Aida refused to comply with the plantation image of black women. She viewed the representation of refined African American types on the stage as important political work. A talented dancer, Aida improvised original routines that her husband eagerly introduced in the shows. When In Dahomey toured England, Aida was invited into the homes of the British elites for private lessons in the exotic cakewalk that the Walkers had included in the show.

After a decade of nearly continuous success with the Williams and Walker Company, Aida’s career took an unexpected turn when her husband collapsed on tour with Bandanna Land. Aida took over many of his songs and dances inBandanna Land to keep the company together but, in early 1909, the musical closed and Aida temporarily retired from stage work to care for her husband, now clearly seriously ill. Recognizing that he would not recover and that she alone could support the family, she returned to the stage in Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson’s Red Moon in 1909, and she joined the Smart Set Company in 1910. Aida also began touring the vaudeville circuit as a solo act. After Walker’s death in January 1911, Aida signed a two-year contract to appear as a co-star with S. H. Dudley in another all-black traveling show.

Although still a relatively young woman in the early 1910s, Aida developed her own medical problems that limited her capacity for constant touring and stage performance. As early as 1908, she had begun organizing benefits to aid such institutions as the Industrial Home for Colored Working Girls. She also took an interest in developing the talents of younger women in the profession, producing shows for two such female groups: the Porto Rico Girls and the Happy Girls. Aida Overton Walker died of kidney failure on October 11, 1914.

Dusky Dinah

Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Title of Song: Dusky Dinah: Cake-walk and patrol

Composer: Sullivan, Dan J.

Illustrator: Fisher, L.S.

Publisher: Chas. Shackford

Year & Place: 1899, Boston, Massachusetts

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music B-308

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: hasm.b0308

Basic Description

An African American woman is shown seated on the branch of a tree, strumming a banjo and looking toward a spindly chicken standing beside her. The round-faced woman wears bows on her shoes, on her neck, and sports a large hat with ostrich feathers. The background for this scene (executed as a red and yellow lithograph) is a huge full moon and linear striations.

Personal Description

The red and yellow color scheme gives this image a light-hearted, playful air, as do the comical renderings of the woman and chicken. Clearly, the illustrator is relying on the stereotypic idea of African Americans playing banjos and desiring chickens to the extreme, hence the ogling at the chicken.

Reality Check

Pauline E. Hopkins (1859-1930)

Boston, Massachusetts-based writer Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins is best known for four novels and numerous short stories which she published between 1900 and 1903. Her best-known work, the novel Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South, was published in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1900 by the Colored Co-operative Publishing Company. Hopkins followed this first novel with three serialized novels – Hagar’s Daughter: A Story of Southern Caste Prejudice, Winona: A Tale of Negro Life in the South and Southwest, and Of One Blood; Or, The Hidden Self, which appeared in the Colored American Magazine. Through her editorial work, fiction, and a substantial body of nonfiction that addressed black history, racial discrimination, economic justice, and women’s role in society among other topics, she emerged as one of the era’s preeminent public intellectuals.