BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY

BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY

BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY

*Joe Von Battle – Requiem for a Record Shop Man*

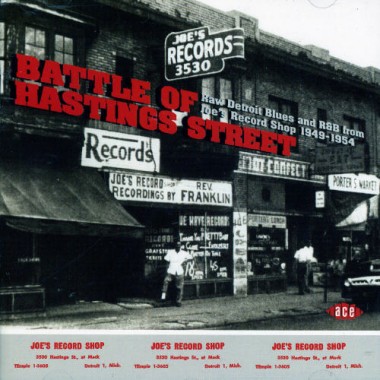

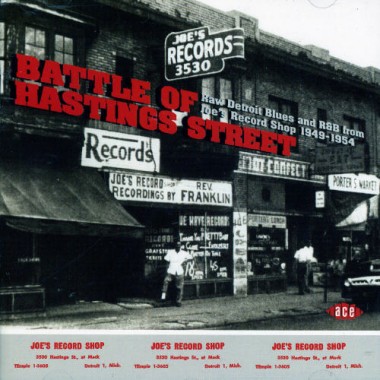

CD cover of “Battle of Hastings Street”, Ace Records, Ace Records.com. Original photo by Jacques Demetre, 1959

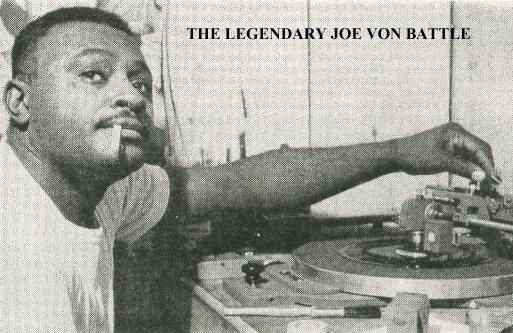

My father, the late Joe Von Battle, was an important mid-century recorder and producer of blues and gospel music in Detroit, from 1945 until 1967. He has been called the “Chess of Detroit”, referring to the iconic Chicago Record company, and is regarded by many as a cornerstone in the building of the “Detroit Sound.”

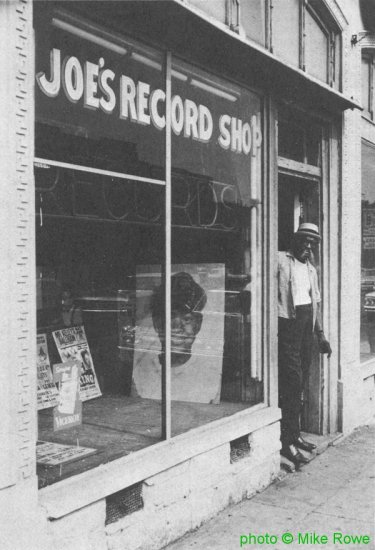

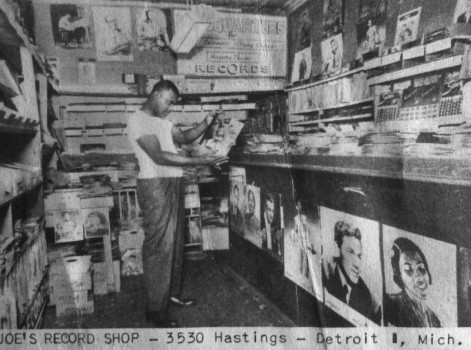

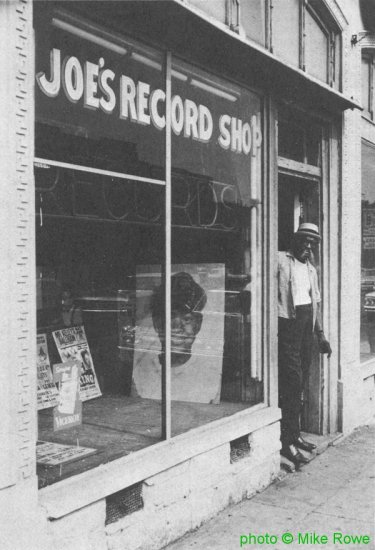

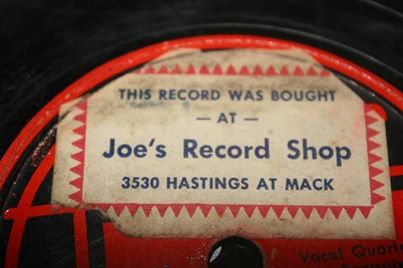

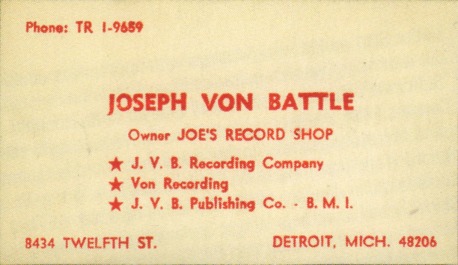

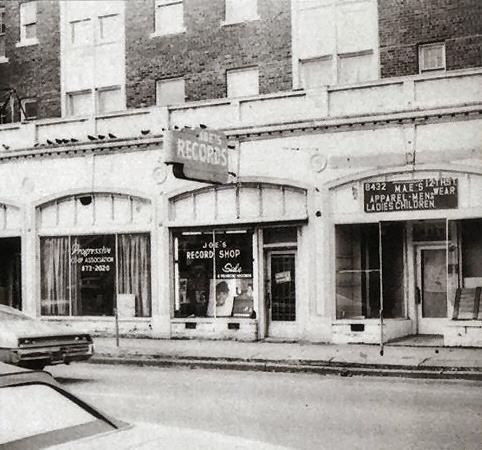

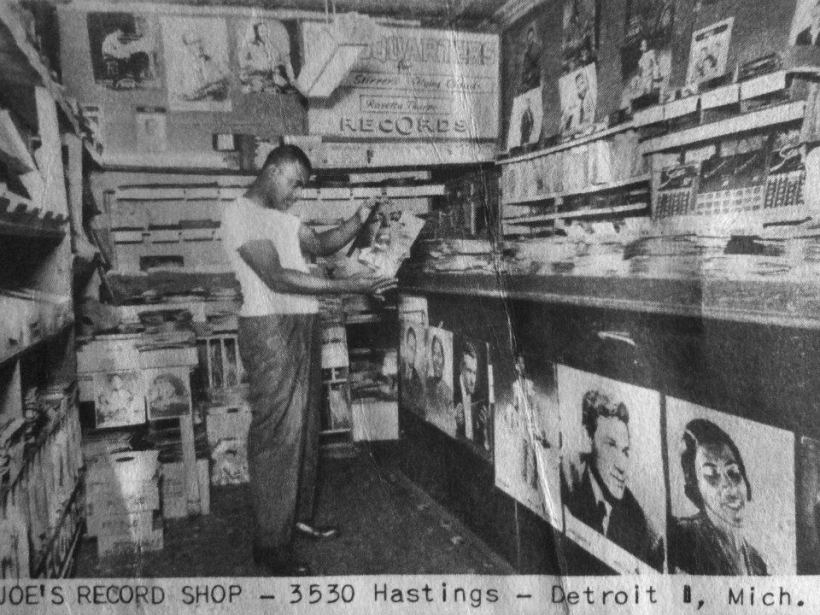

Joe Von Battle is believed to be the first African-American post WWII era, independent record producer in the U.S., and owned the legendary Joe’s Record Shop, at 3530 Hastings Street. There is no disputing his significance.

After the demolition of Detroit’s Black Bottom, in the late 1940’s, Hastings St. survived until about 1960. The record shop was then demolished to create the I-375, aka Chrysler Freeway. After the destruction of Hastings, the record shop moved, with other surviving businesses, to the West Side of Detroit, on 12th St.

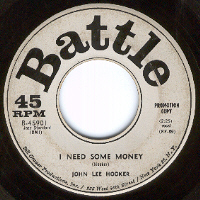

Over the years he recorded legendary artists such as John Lee Hooker, Little Willie John, Johnnie Bassett, the Violinaires, the Serenaders, Little Sammy Bryant, Little Sonny, Jackie Wilson, Sonny Boy Williamson, and many, many others in his studio in the back of the shop, including a classic called The Hucklebuck by Paul Williams.

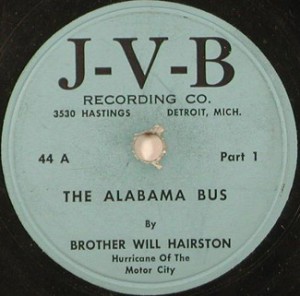

He even recorded a Civil Rights song “The Alabama Bus,” by Brother Will Hairston (backed by Washboard Willie), an obscure but significant Blues chronicle of the Alabama Bus Boycott (more on this historic record on another page of this website, see index).

The classic Detroit blues record, “Hastings Street Opera”, which mentions Joe’s Record Shop in its lyrics, was recorded by a gentleman who went by the name of Detroit Count and sang up and down the streets of Hastings, outside the record shop.

After coming to Detroit from Macon Georgia, Joe worked for a while at the Eastern Market and dug ditches for the gas company. He later worked at the Hudson Motor Car Co. and, for a time, worked two jobs, like many Detroiters in those times – after the end of his shift at the Hudson plant, he’d walk across the street to work at Chrysler for another 8 hours. At the end of WWII, he became one of the last hired, first fired after G.I.s came home from the war; the whites returned to their jobs, displacing the black workers who had been “last hired” during the war. He was let go from his factory job – and Joe Von Battle vowed he would never again “work for another man.”

In 1945, a Jewish widow who was selling out her business offered him a deal on her storefront, and soon he opened up shop. In the Chronicle he said, “I saw a man putting a “closed” sign over an establishment, inquired, and found myself in business – selling records from my personal collection for 25 cents.” As he said in the Michigan Chronicle newspaper, in 1948, he was determined to be his own boss, though in “his pockets nothing more than a pack of cigarettes,”; he began by selling his own records from his house, up and down Hastings Sr.

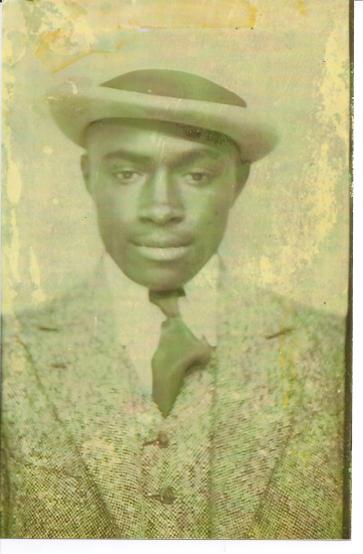

In the same article, he states that he was making $100,00 dollars in sales (a formidable sum in those days), with an inventory of 35,000 records by the late 40’s.He became known near and far in Black music circles of the time as “The Mighty Joe Von Battle.” My father was born Joe Battle, but he always admitted to the elegant pretension of adding the Germanic/European “Von” to his name when he was a young man, the result of seeing many afternoon movies that starred the Austrian actor, Erich Von Stroheim.

A survivor of Southern Jim Crow and Northern discrimination, years later, he came to understand as well, after he began his recording business, that adding “Von” to Battle had served to obscure his African-American identity to various long-distance record and radio executives who would not deal fairly with Blacks. The might tolerate a black artist – singer or dancer – but had no use for an African-American man as a recorder or producer of music.

Joe Von Battle became known by many in the record industry as “Von Battle”, in the European way (like Von Trapp), to his advantage. But in real life, he – a down to earth, Southern man – used “Von” as just a middle name.

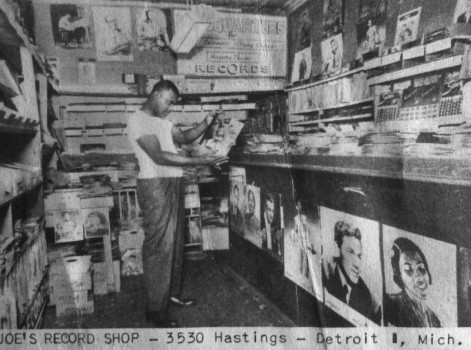

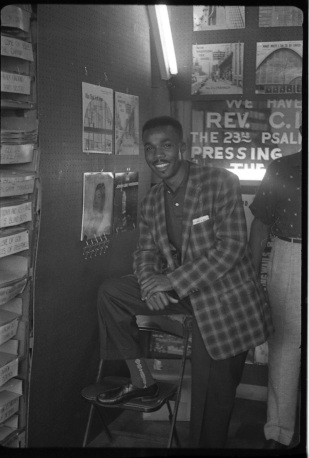

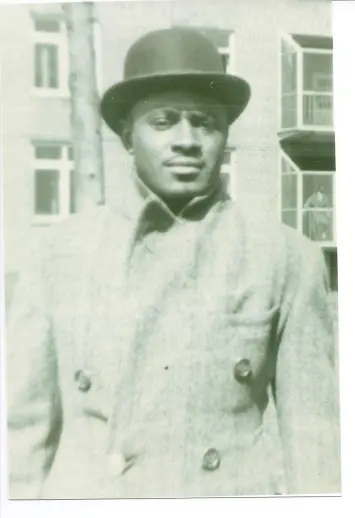

Joe Von Battle, in the front of Joe’s Record Shop. Approx. 1953. Photo by Joe Von Battle Jr. (?)

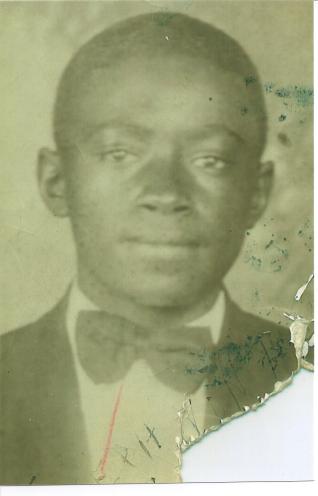

Joe Von Battle was born in Macon, Georgia in 1915, and arrived in Detroit in the 30’s during the great migration of Blacks from the South. He and his first wife, Clara, and 4 children – Joe Jr., Joanne, Peggy and Phyllis – were among those who up North to Detroit and moved from “Black Bottom” to the Brewster housing projects near Hastings. For in those days, public housing was so coveted and the competition over housing was so great, that Whites fought to keep the projects to themselves.

In fact, this belies the popular fiction that those from the projects – like Diana Ross – had a hardscrabble upbringing during those times. For the projects – in those days of segregation in the North – were filled with upwardly mobile working folk, who had moved up from the crowded, substandard housing of the Black Bottom area that was teeming with folks who’d come up from the South. In fact, the Detroit Race Riot of 1943 was instigated by the intense competition over housing in the city, which exploded into violence when whites tried to stop blacks from moving not the Sojourner Truth Projects on the near East Side.

As a young man in Georgia, Joe Von Battle had been a licensed African Methodist Episcopal Minister in training, going from church to church, listening to preachers and learning about the ministry. But, after living in Detroit, he became deeply disallusioned during an episode of quarantine for suspected tuberculosis (that turned out to be pleurisy of the lungs).

When released, many months later, he had lost all, and had to begin anew to find a way to support his family. This is a little recounted part of Detroit’s history, in which Blacks and the poor lost income and property in abrupt, sometimes premature diagnoses. This was often due to crowded living conditions and a lack of available health care, especially in Black Bottom. These patients often endured demoralizing quarantines for months and even years.

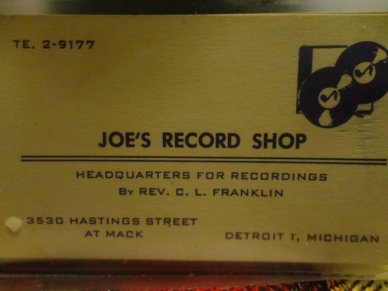

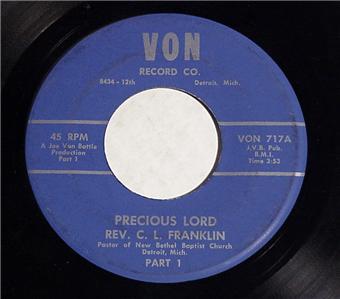

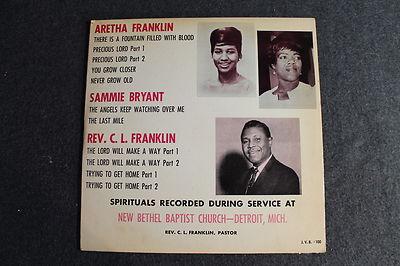

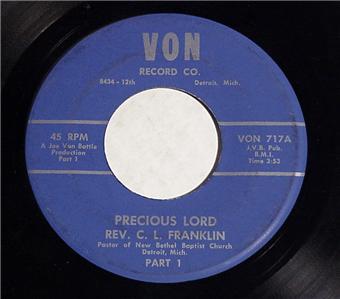

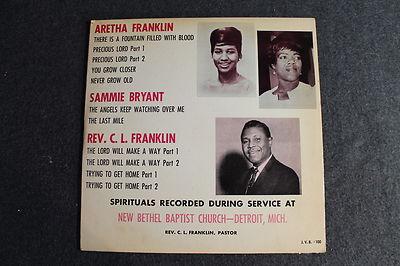

My father abandoned the ministry, though his affinity for sermonizing and gospel music was to endure, taking the form of recording the preaching and singing of others. He produced the Rev. C. L. Franklin, Rev. Cleophus Robinson, Rev. Jelks, Bro. Willie Hairston, the Violinaires, and others.

My father was a producer of Gospel, Blues, early R& B, and what came to be known as Rock ‘N Roll.

Battle label 45 record, “I need some Money”; by John Lee Hooker. Photo from jlhvinyl.com

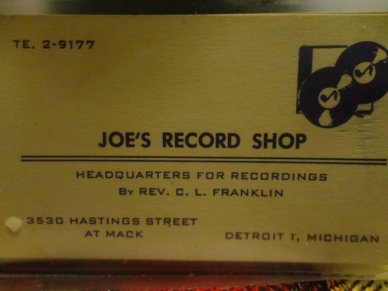

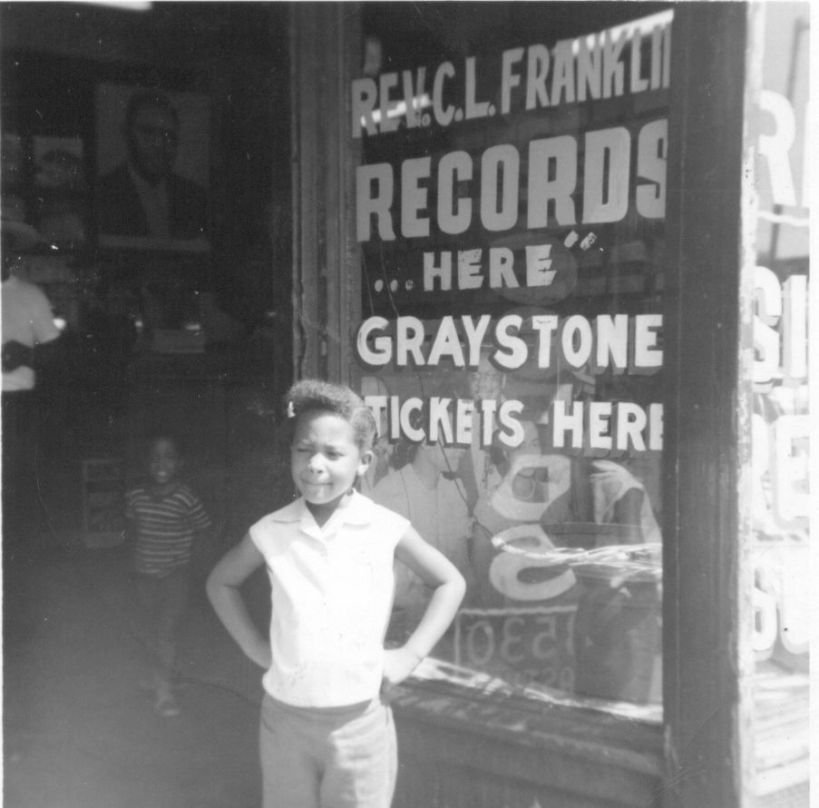

Down Hastings Street was New Bethel Baptist Church, and Joe Von Battle began hearing about the extraordinary preaching of the Reverend C.L. Franklin (father of Aretha). Reverend Franklin’s church services were played live on radio and heard far and wide in the Detroit area and beyond; he was already regarded a phenomenon – “a preaching machine.” My father heard about Franklin’s gifts as preacher and singer, and he began visiting the church to hear “the man with the million dollar voice.”

Soon Joe was recording Rev. Franklin’s Sunday night sermons and songs, mostly on the Battle and Von labels. Joe Von Battle was the sole producer/recorder of the sermons of Rev. Franklin, and this was a relationship – and friendship – that was to last through 75+ albums and records, for many years.

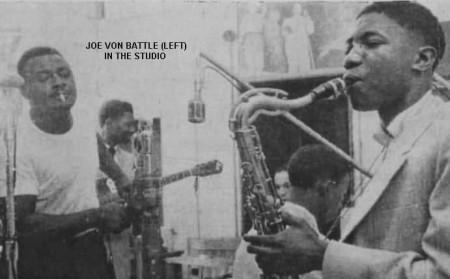

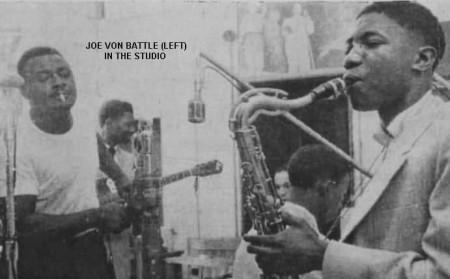

Joe Von Battle, left, and Rev. C.L. Franklin, right, in Joe’s recording studio in the back of the record shop. Franklin began recording with Joe in 1953.

Joe Von Battle was the first to record the voice of Aretha, Franklin’s daugher, as she sang in the New Bethel Baptist church choir. He produced her first record, the gospel song, “Never Grow Old” when she was 14. He produced many of her gospel songs before she moved to the larger record labels to sing secular music.

My father initially released and distributed the records himself, mailing them all over the country as demand for them increased. After a time, the songs and sermons of especially Rev. Franklin were mainly released and distributed by Chess records, where my father had numerous recording and financial arrangements.

Many of his Blues recordings were regarded as simple, even crude, done as they were on a basic machine in the back of the storefront, with it’s simple microphones and an old upright piano. Many a night after church, Ms. Aretha sat playing that piano and having a good time with my older half-brother and three half-sisters, who worked at the shop with my father (in later years, my brother and I surely plunked that old instrument out of tune). Joe’s recordings of Rev. Franklin’s sermons, done at the church, were clear and electrifying, capturing the excitement of Rev. Franklin’s choir and church services.

My father would play Rev. C.L. Franklin records through loadspeakers onto the street, and passersby would gather in great crowds to hear the sermons and psalms; the police often came to control the crowds. The very idea of throngs gathered, enthralled, listening to Gospel music, surely flies in the face of the reputation of Hastings Street as only a “red light district”.

Musicians from far and wide found their way to Joe’s Record shop. Today, the remaining Blues and “religious” records that he recorded are repositories of an important part of the history of early R&B and modern Gospel. They are pure, raw and unadorned by later contrivances and techniques.

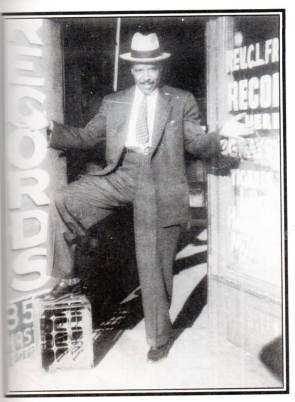

Joe Von Battle, in front of his record shop and the barber shop next door. Photo by Joe Von Battle Jr.

By the 50’s my father was famous in Detroit and beyond for his record shop/studio on the infamous Hastings Street. Hastings, starting at Gratiot in Black Bottom, and running North until West Grand Blvd., was a thriving, intense commercial center, as well as an entertainment district.

It was a teeming part of the Detroit metropolis, with people of various European ethnic backgrounds and businesses, Jewish folks and Blacks. In fact, it was the center of African-American business in Detroit, with Blacks owning pharmacies, grocery and furniture stores and the like.

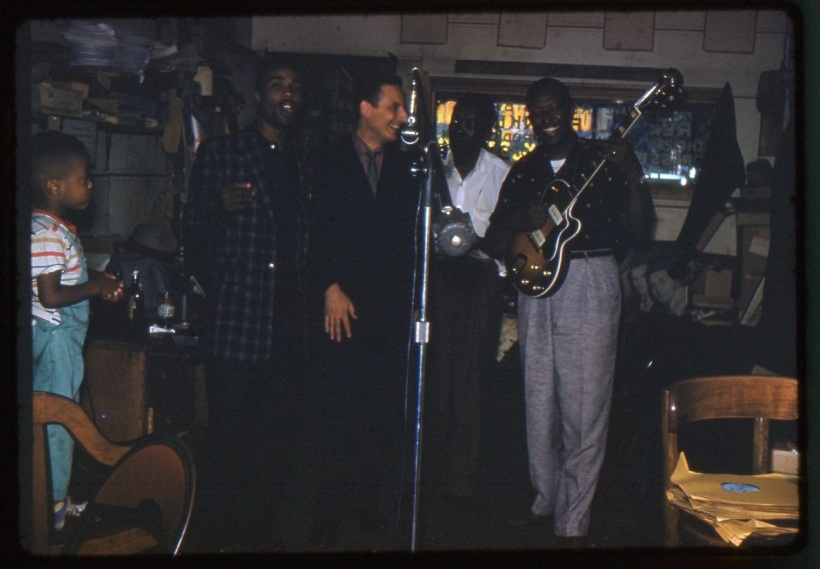

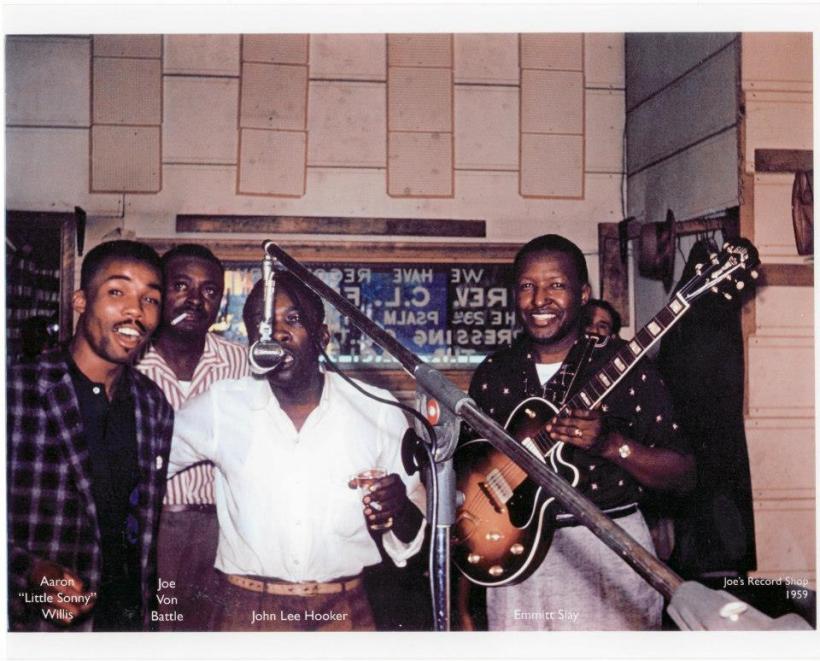

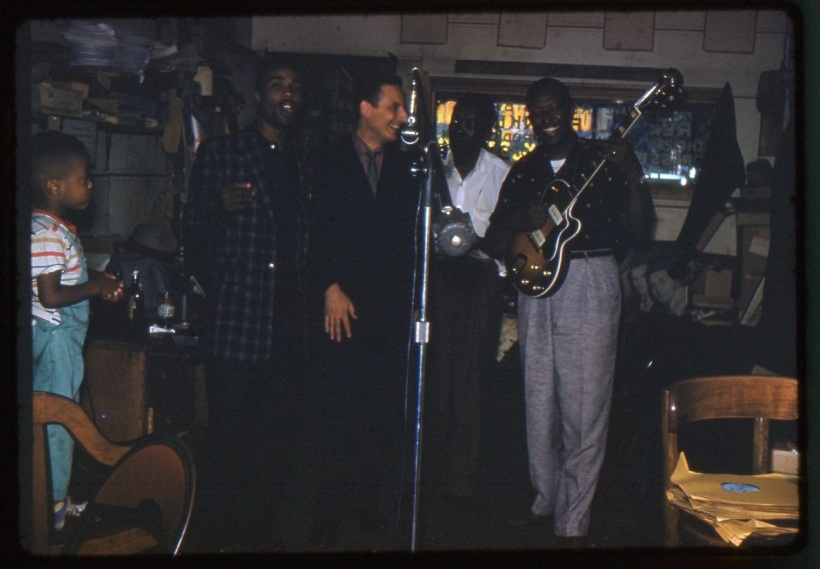

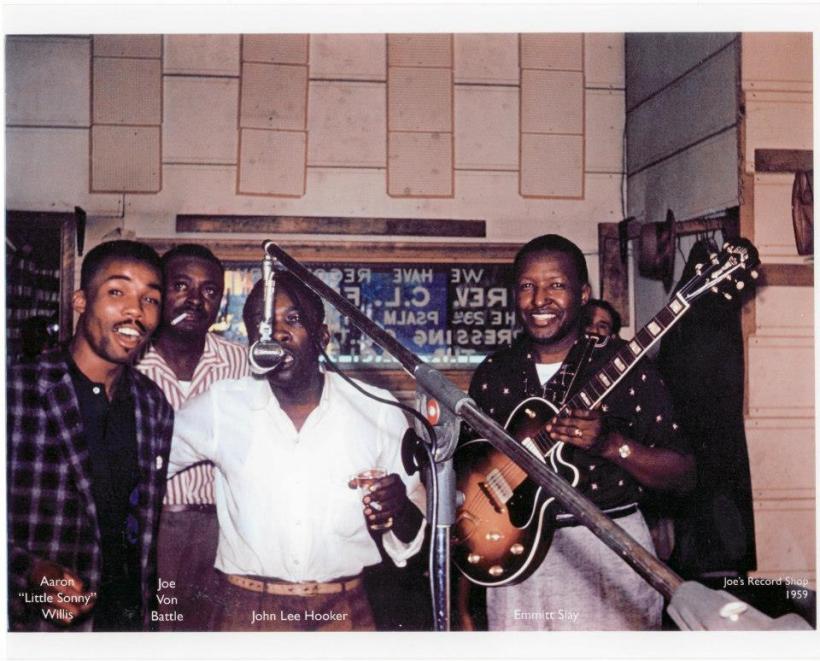

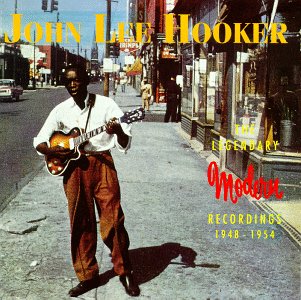

[From my article on this site, John Lee Hooker – No Magic, Just Man: One day in 1959, a photographer – Jacques Demetre and a writer, Marcel Chavaud; came to the United States from France; they were writing a book about the Blues – and they stopped in three cities – Chicago, New York and Detroit. When they got to Detroit, they went straight to Joe’s record shop, as they had heard that it was the place for the Blues.

My younger brother, Darryl Battle, looks on at Aaron “Little Sonny” Willis, Jacques Demetre, John Lee Hooker and Emmett Slay.

When they arrived, my father picked up the phone and called his friend Aaron Willis, aka Little Sonny, and told him to come over; there was a man from France come to take pictures of the men of the Blues. He made another call too, and when he came from around the corner of Mack, onto Hastings and into the shop too, my older brother Joe Jr. says that the French photographer almost fainted, he was so astonished and delighted to see the already legendary Bluesman – John Lee Hooker – come into view.

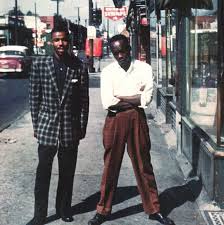

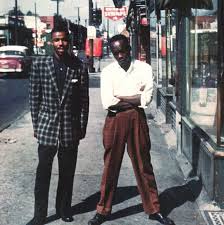

Aaron “Little Sonny” Willis and John Lee Hooker, in front of Joe’s Record Shop. Photo by Jacques Demetre, 1959.

Demetre snapped John Lee Hooker in front of the record shop (above) and eventually, the photo that he took became an iconic album cover; John Lee, dapper in slacks and white shirt, posed with his guitar on the sidewalk in front of the record shop, in the same spot where my father, mother and her sisters always stood for photos back in the day.

The camera faces North, up Hastings Street; the spire of St. Josophat on Canfield is in the background on the left. Hastings is long gone, most of it is a freeway service drive now, but that church is still there, one of the few remaining structures adjacent to Hastings St., from back in those days.

Aaron “Little Sonny” Willis, Joe Von Battle, John Lee Hooker, Emmitt Slay. Photo by French photog Jacques Demetre; writer Marcel Chauvard in background.

Several amazing Blues photographs came from that shoot. Some of them were in amazing color for the time. As of this writing, photographer Jacques Demetre is still alive in France – a nonagenarian – and remembers his long ago visit very well – and my brother, Joe Jr. almost 80, recounts it like it was yesterday.

Joe Battle Sr., Joe Battle Jr. and Floyd Taylor. In front of the Hastings St. record Shop. Photo by Jacques Demetre, in rare color for the time, 1959.

Berry Gordy would come and talk “record talk” as he began his own fledgling company at the house on The Boulevard (i.e. West Grand Boulevard) that he was to call Hitsville. Many Motown artists visited the shop for a good conversation and a “taste” in the back room. Artists such as Mary Wells, bassist James Jamerson and other Funk Brothers, and many others “hit a lick” at Joe’s Record Shop, and many recorded there.

Daddy’s record labels were “JVB“, “Von” and “Battle“, Gone, Viceroy and perhaps more, as well as subsidiary arrangements with several labels such as King and Deluxe.

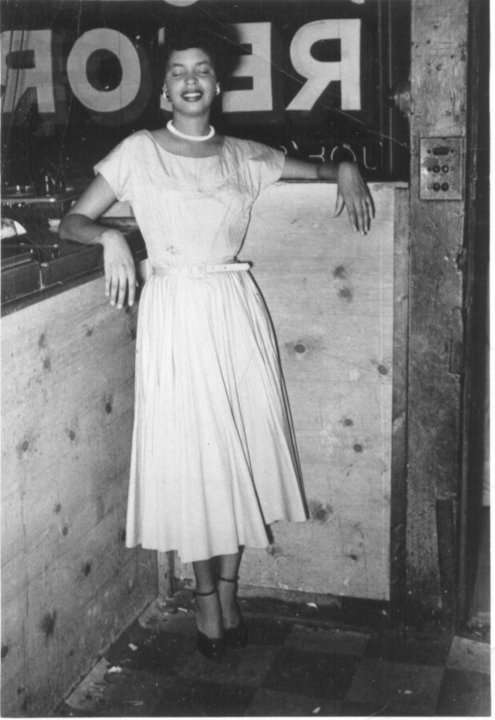

Daddy was handsome and famous up and down Hastings and beyond, with a gold tooth in his smile and a gold Lincoln Continental. He was many years older than my mother Shirley, his second wife.

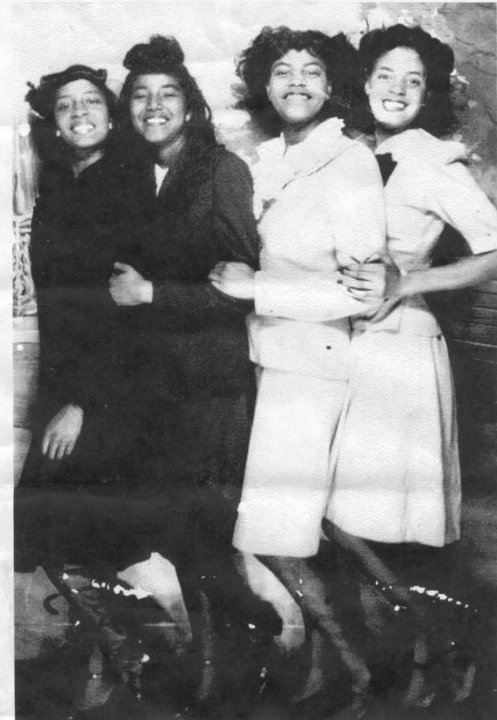

She was one of five pretty sisters whom he met while she was at the bus stop in front of the record shop, on her way home from their Sanctified church around the corner, on Mack Ave. – Zion Congregational Church Of God In Christ. It was founded and headed, at that time, by the great Pastor I. W. Winans (patriarch of today’s Winans musical family). The church was and is known in Detroit’s COGIC church world and beyond – due to it’s location -as “Mack Avenue.”

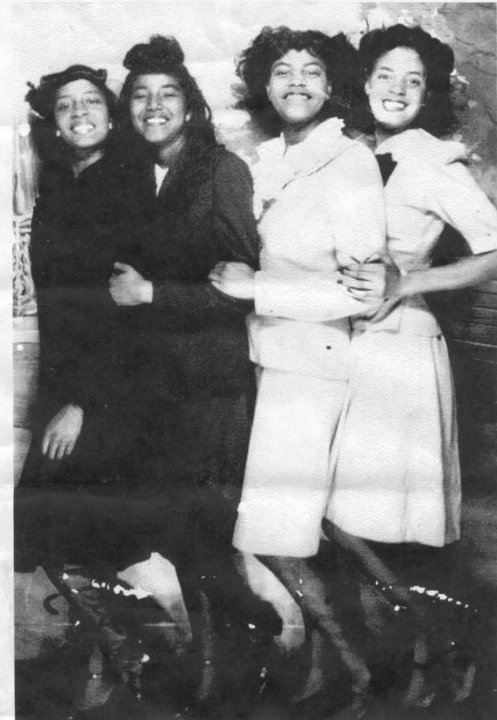

My mother, far right, next to her sister, Lillian, visiting their Chicago cousins, in their dark suits on the left.

My mother’s Pentocostal church upbringing of the time allowed neither movies nor secular music; doubtless, the ceaseless excitment andnightlife of this exciting music man called Joe Von Battle, and his Hastings street shop, was mesmerizing to a young beauty who loved experiencing “the world.”

She was an music lover, though she never had a love for the Blues that was so dear to my father’s heart; she had more modern, popular tastes. Nevertheless, she worked at the record shop for several years before they married. Her good looks and musicality were as appealing to the customers as my father’s charismatic presence.

Suffice it to say before long, there was a scandalous overlap between my father’s first wife, and his relationship with my mother, though they eventually married. Despite all, I arrived in the world of my beautiful mother and her five beautiful sisters, and my father, a brown, handsome music man of local fame. My early years were spent in the bright rays of her beauty and his renown.

My father was a fast, entertaining talker – a real raconteur; a sharp-dressing man with a grade school education. He was a voracious reader who kept stacks of news articles and volumes of the classics, tales of the Iliad and Odyssey and Black history that he allowed me to read.  He was a lover of animals, keeping wounded birds, dogs, cats and any hurt thing that hobbled along on Hastings, and later on 12th, nursing them back to health – cooking his chicken and rice concoctions on a hot plate in the back of the shop.

He was a lover of animals, keeping wounded birds, dogs, cats and any hurt thing that hobbled along on Hastings, and later on 12th, nursing them back to health – cooking his chicken and rice concoctions on a hot plate in the back of the shop.

He was a lover of animals, keeping wounded birds, dogs, cats and any hurt thing that hobbled along on Hastings, and later on 12th, nursing them back to health – cooking his chicken and rice concoctions on a hot plate in the back of the shop.

He was a lover of animals, keeping wounded birds, dogs, cats and any hurt thing that hobbled along on Hastings, and later on 12th, nursing them back to health – cooking his chicken and rice concoctions on a hot plate in the back of the shop.

He wrote and published songs but was never really a singer or musician. What he had was a magnetic personality, an ability to discern talent in others, a fascination with recorded sound – and a love of making money. He would record virtually anything that made music or noise. He was a dedicated provider his two families – four children and his ex-wife from his first marriage, and four children and his wife in his second, in the days before child support or welfare. Despite the breaking of his first marriage, his older children loved my mother, and loved us, the children of his second marriage; we spent much time together when we were growing up.

Joe’s charisma, love of hustle and desire to provide for his both families was such that when record sales were slow, he thought nothing of having his son Joe Jr. help him sell sugarcane, or even straw hats, at the front door. Maybe that’s why, in the record Hastings Street Opera, the Detroit Count rapped “…Joe’s Record Shop, you can get anything there but a T-Bone steak.”

As his production of Rev. C.L. Franklin’s records grew, Joe’s Record Shop was associated with a Gospel radio show, hosted by the highly respected radio personality, Senator Bristol Bryant.

The Gospel classic, “Precious Lord” by Rev. C. L. Franklin, on the Von label; photo from Ebay Seller AuralEffects

Joe Von Battle also purchased air-time for his own show, and broadcast from CKLW in Windsor Canada, across the river from Detroit, a station with a signal so famously strong that the shows could be heard throughout regions of the South. Each week the tapes from the show were delivered – often by Joe’s eldest son, Joe Jr. – to the station’s American business offices in the Guardian Building in Downtown Detroit.

With African-Americans moving from the South to the North, hungering for connections back across the Mason Dixon Line, Rev. C.L. Franklin and Joe’s Record Shop became mythical in thousands of Black households in the U.S., as they tuned in for the ritual Sunday night sermon and Gospel music.

[I was on the radio show myself. In elementary school, I won first place for a poem I had written, and I got to read it on the show – my media debut.]

My father’s shop was the place for hanging out, with folks like Jackie Wilson, impresario Sunny Wilson, B. B. King, and some of the last of the old “Blues Boys” – Sonny Boy Williamson, John Lee Hooker, Joe Weaver, Eddie Burns, Bobo Jenkins, Little Sonny, Little Willie John, and a who’s who of black music of the times, from the clubs on Hastings and in Paradise Valley.

Having fun in the back of the Hastings St. shop; my mother, at right in plaid, and her two of her five sisters, standing. My father is just out of camera.

Joe Von Battle’s success was real, with a magnificent home in Highland Park, where I grew up, a beautiful new stay-at-home wife, and a second family of four kids (of which I’m the eldest).

My parents’ lives, in the 50’s and early 60s, were filled with parties, clubs and horseback riding at Idlewild, the now historic all-Black resort in Northern Michigan, the only place of such leisure open to Blacks in the days of segregation. He was an avid golfer and, with my party loving mother, was a “Man about Town”. They lived a grand life for the times.

His eldest son Joe Von Battle Jr., as handsome as his father, worked alongside him after school and on weekends at the shop, since it opened in 1945, until having his own family and the lure of factory pay at Chrysler in the 1960’s pulled him away, to my father’s great grief. My brother Joe Jr., is another great storyteller with a near photographic memory, and has shared many memories with me, about those times.

In 1960, after Hastings street was urban renewed into the Chrysler Freeway, my father was forced to move his record shop from the East Side of Detroit to the West, across town to 12th street.

This massive shift was an historic urban migration, uprooting the community – including many Hastings business folks – from their entrepreneurial and residential roots – a destruction of generational wealth from which our community has never fully recovered. Many of them, having already survived the migration from the South, could not withstand yet another traumatic transition, and many African-American businesses were lost forever.

My father and I often to back to the old Hastings St. as the freeway encroached its way North. Once, I remember we stood on the banks of the dirt-filled crevass, the initial diggings of the Chrysler Freeway. My daddy looked across the giant pit, to the place where his record shop once stood, and he shook his head and said, “That used to be Hastings.”

The Record Shop moved from Hastings Street on the East Side, over to the West Side, on 12th Street and Pingree, then later, a few blocks away, to 12th Street and Philadelphia, where it would remain.

The 12th Street Shop was not far from new Motown house called Hitsville, and though my father disliked the new sound – locked back, as he was, in his down-home Blues and Work With Me Annie taste in music – he was great friends with many of the Motown folks. Many of the Motown artists found their way to the shop for a “taste” and some conversation with Joe, too.

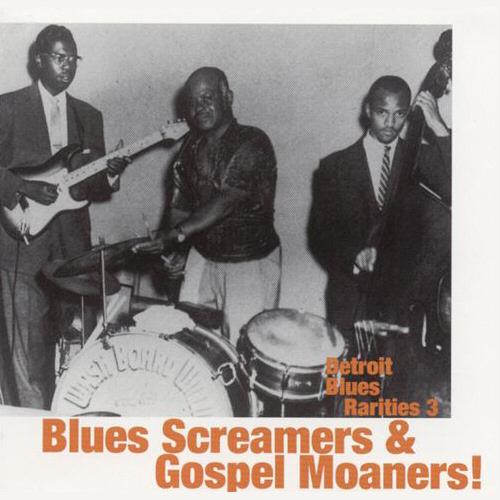

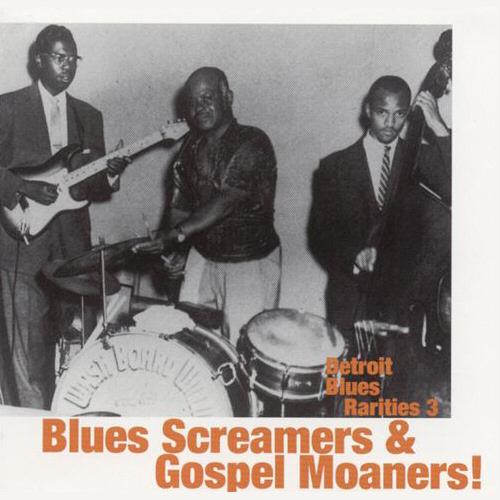

Mack Chimse, Washboard Willie and James Jamerson – who would become Motown’s bassist and Funk Brother. Album Cover, George Paulus Production

Here was the world of 12th Street of Detroit, with its intense daytime commerce and after-hours, huckle-buck nightlife; where men drove Eldorado’s with matching suits, and women wore wigs and smoked in public. But with all of its roiling activity, 12th street was not the same as the life on Hastings; although folks had come from Black Bottom, there was also a new, more urban population, many of whom disdained the old country blues that my father loved and sold records to back on Hastings St.

In the midst of these changes, my father grew desperately ill, and no doctor could figure out the cause; he was becoming weaker by the day, and his skin, usually a pecan brown, was turning to a deep black. Finally, on deaths’s door, he found a new, young doctor who diagnosed him with Addison’s disease, a little known malady of the pancreas, that happened to afflict President John Kenny, too ( a fact of which my father was inordinately proud). He was put on new, miracle drug called “cortisone”, and was on this medicine for the rest of his life.

Though things were different, we became a part of the West Side life – we’d have breakfast at the Cream of Michigan cafe, daddy would drive a few blocks and get corned beef from the Jewish deli called Esquire, and we’d watch folks with fringed, spangled dresses and silk-and-wool suits, who had just left a night of partying at the 20 Grand and after hours clubs join the church folks having a bite before Sunday service.

I

I spent weekends and summers of the 60’s with my younger brother Darryl splicing tapes, reading Billboard and ringing up the latest 45’s, and mastering the art of discerning a customer’s request within a song’s first bar (an unfair music trivia advantage that we retain today).

I remember many a Saturday afternoon in the later days of the shop, affixing labels to records, unloading them from boxes, and always, playing all the music we wanted and doing the Shing-a-ling and Boo-ga-loo in the middle of the floor, to the delight of the customers and the chagrin of my father, who wanted us to get back to work and sell records (ignoring the fact that, dancing was the best way to sell them).

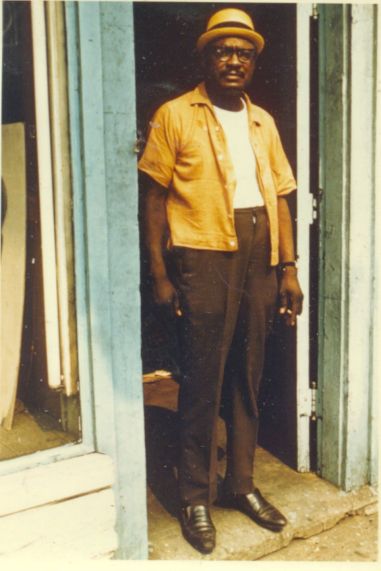

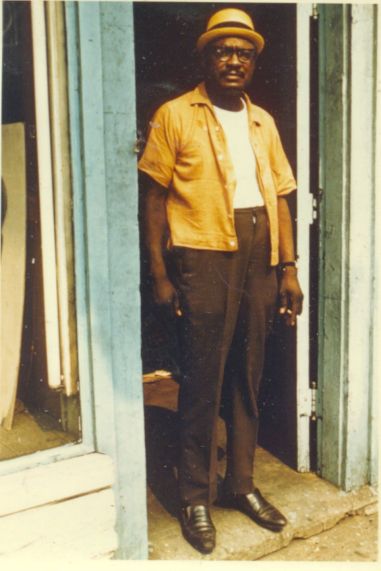

Joe Von Battle, in the doorway of his record shop on 12th St. A large photo of my younger sister in the window – he was proud of her good report card. Circa 1966.Photo by Mike Rowe.

Sometimes our baby sister and brother, Andrea and Lawrence, would come too, and Darryl and I – old and experienced pre-teens – would have to keep them from getting too exposed to the 12th street life. We’d spend all day dancing and playing the records the customers wanted to hear and buy.

I remember when I went “up North” with Daddy to the record pressing plant in Owasso, Michigan, or to Chicago to see the Chess Brothers, Phil and Leonard, where I listened to Bo Diddly masters – with Bo Diddly. Years before me, my elder half-brother Joe had sat in the Chess studios talking with Muddy Waters and the Chicago “Blues Boys”. I was a full-grown middle-aged woman before I understood that the box lunches my mother prepared for our trip were made because we could not depend on being able to eat at the roadside diners and rest stops, due to the still intense segregation, even up North.

Joe Von Battle, left, in the studio on Hastings St., From Marv Goldberg’s R&B Notebooks website, The Thrillers. Photographer unknown.

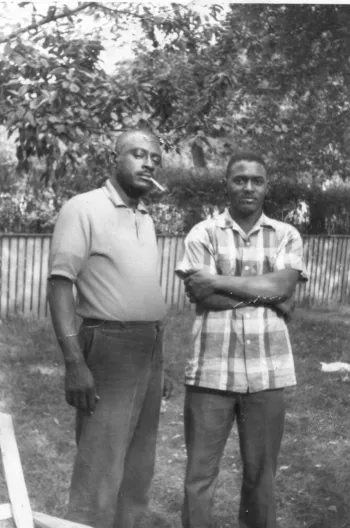

Our father’s Blues friends were a part of our life. Wilson Pickett laid the sod in our front yard in Highland Park, taught my younger brother Darryl how to push the giant roller over the new grass. Famous blues men helped my father do repairs on his house, and shared a drink in the back yard, but to us they were all just Daddy’s friends from “Down South.”

On many Sunday nights, Darryl would go with my father to New Bethel Baptist Church, now on Linwood on the West Side, just like my father’s oldest son, Joe, before him on Hastings, dragging the mics and tape recorder in the big leather case to record the next homiletic masterpiece by “Frank”, as my father called Rev. C.L. Franklin.

After the mics and tape recorder was set up, my brother would sit behind the pulpit with the deacons, his legs too short to reach the floor, dangling from the big chairs on the altar. Then they all set to listening to Rev. Franklin whoop and sing and teach the urban Gospel (though often, my little brother would fall asleep in the middle of the making of music history).

Joe Von Battle at his reel-to-reel.

My father recorded everywhere, obsessively; in the back room of the shop, in pulpits, in the streets, in our living room – once I came home from school to the sight of his amps and mics trained on man called Washboard Willie playing the – you guessed it – in our back yard. This, to cool, pre-teen me, was an act of bumpkinism that embarrassed me to no end in front of my Beatles and Motown loving friends.

I spent most weekends and summers working at the record shop, during the tumultuous years of cultural change, and cataclysmic shifts in music. Album covers were my windows on the musical world, and I spent hours studying them, and puttering around in the behind-the-counter chaos of plastic red and yellow disks, red and green Scotch tape boxes and slotted metal slabs for splicing tape.

Joe Von Battle, after the move from Hastings, in the doorway of the 12th Street Shop, early to mid-60’s. Photo attributed to Mike Rowe.

As the 60’s progressed, the trends in music had clearly changed in the Black community, and less customers asked for Blues and the old music. Motown – “The Soundtrack of Young America” – the new Soul music, Rhythm and Blues – and even Rock ‘N Roll – were now what customers wanted. This was all to my delight at the record shop turntable – but to the chagrin of my father, who still insisted on trying to to sell the Blues. On Sunday mornings he still – defiantly – played the old Gospel for the passersby, who were increasingly listening to the “new music” and leaving the old sounds behind.

The inroads of the big record sellers also took it’s toll. I remember walking with my father through Sears and Roebucks in Highland Park, where there was a “new, improved” record department, chock full of many of the records he was trying to sell on 12th street – and Sears was selling them at a much cheaper price.

To our shock, there were rows and rows of Black music, which years before, Sears and other big sellers would never have handled in such quantities, calling it “race music.” My father became a broken man – at home and at work. At the time, I didn’t understand his grief and fury, the fact that we were in the maelstrom of the destruction of the independent record sellers and producers of that era.

JVB and my mother, Shirley, in our Highland Park back yard (our dog had busted through our back fence). Mid sixties. My father’s skin had turned dark, from Addison’s disease.

To add to this commercial and musical threat to Joe’s life’s work was two afflictions – Addison’s Disease, and chronic alcoholism. The many “tastes” in the back room of the record shop and at the bars on 12th street had long before morphed into full-blown alcoholism. My mother’s love for parties and the Twenty Grand club took it’s toll, as well. If my early years were spent in their amazing, musical life, by the time I was in middle school, the parties that they loved had turned into the insanity of drink and vicious marital wars.

My brother Darryl and I, young teens, ran the record shop on the weekends in those days, aware that our fun, weekly chore was now helping to keep the shop alive. My father was a shell of his former self; tormented, tormenting and addled by drink; our family suffered mightily.

There were record collectors who acquired records and materials from Joe during that time. There were also record sharks in the business, who moved in to take advantage of his decline and his desire to share the music of his life – as well as his need to support his second family. Some acquired masters and tapes less than scrupulously, as he weakened.

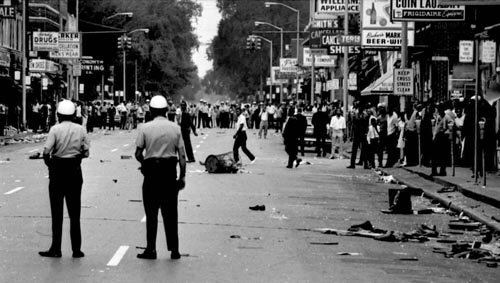

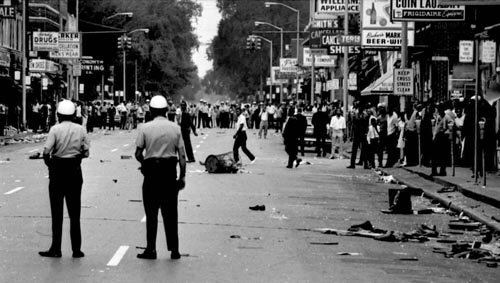

The beginning of the end came on July 23, 1967; a wave of destruction and police violence made it’s way down 12th Street, to become Detroit’s 67’ Riots – also known as The Rebellion. My father’s record shop was in its path. But that is a whole ‘nother story.

12th Street scene during ’67 Riots. Joe’s Record Shop in foreground outside of view, right side side of street. Iconic Stock photo.

I think that Joe Von Battle really died the day he returned to his shop, to trudge through mounds of charred and melted records and fire-hose soaked reel-to reel tapes, unwound and slithering like water snakes; thousands of songs, sounds and voices of an era, most never pressed onto records – gone forever.

He was never the same, and neither was our home-life. But he wasn’t actually pronounced dead until 1973, doubtless from complications from the Addison’s disease that he had for years, and from more than a few “tastes” too many in the back of the shop, at our backyard bbq’s, and increasingly, after the loss of the shop, just ceaseless drinking at home on the couch.

A long time friend, Dave Usher (who was to become the manager of Dizzy Gillespie) extended help to Joe, allowing hm to work for a time on the ships of his family’s business on the river. But it was too late; Joe had never again “worked for another man” since he opened his shop in 1945, and in the bedraggled shape he was, it was not time to begin. My father drank himself to death, another broken hearted music man.

But even though music had moved on to the new Motown sounds and beyond, and even embittered with life and addled with drink, he always understood the importance of what he had done, what he had captured in those long, brown ribbons of celluloid tape. It was the ending of an era of African American music, and the beginning of another.

****

All of my life, I was accustomed to my father being called, “The Mighty Joe Battle“; in fact he often referred to himself that way, only half in jest. The late Famous Coachman, the grand Blues man of Detroit, always called my father “The Legendary Joe Von Battle”.

In Detroit, at the Charles Wright Museum of African-American history, there have been prominent displays of Aretha’s first record, on the JVB label, sometimes with words about Joe Von Battle, though few in Detroit have known much about him. I am always touched by these museum recognitions.

Early album by Aretha and her father, and the singer, Little Sammy Bryant – who was a ‘little person” with a big Gospel voice.

I have come to know, since I posted my father’s story, that even though he died in relative obscurity in Detroit, there is a significant number of collectors world-wide – in England, Holland, Australia, Japan, Wales, Spain, etc., who are well aware of the work of Joe Von Battle, and very knowledgeable about his voluminous recordings and discography. My father’s records are now collected and sold in auctions online, some highly coveted and worth hundreds of dollars for a single 45 (I cringe when I remember how we played frisbee with them without a second thought, back in the day).

I’ve run across re-issues of music my father recorded; a bittersweet accolade. Yes, it’s hard to see others produce this work for their own gain, but I’m gratified that there are those who value those sounds that he captured forever, over a half-century ago and are producing these records for collectors to enjoy today.

Joe Von Battle deserves special recognition for his role in recording the final songs and sounds as we changed from a people of the rural South into a new, urban community. He recorded the post-war sound of Detroit, and forever etched in vinyl some of the earliest works of those who became household names, as well as those whose music would never have been recorded but for him. May his musical legacy live forever.

In honor of the works and memory of my father –

The Late, Great, Legendary, Mighty Joe Von Battle.

Epilogue:

My father’s first wife, Clara, passed away in 2006.

His eldest son, Joe Von Battle Jr., lives in Detroit, almost 80, and still as handsome as his father. He is a repository of the early history of these first moments in the new music.

His 2 surviving elder daughters, Joanne and Peggy, returned to live in the South.

His younger sons, from his second family, live in Detroit: my younger brother, Darryl Battle, like his father, is a devoted true Blues lover and collector; the youngest, Lawrence Von Battle, inherited our father’s love of recorded sound, and is an expert audiophile.

His youngest daughter of the second family, my sister Andrea Kelly, also lives in the South.

There are many grandchildren, a number of them with some form of the name Joe Von Battle.

My mother Shirley, his second wife, passed away in early 2008. Her “Home Going” was at the old church that she had returned to in her later years, Zion Congregational COGIC, still known as “Mack Ave”.

The Pastor today is Elder James Hall, and among the many singing Saints in attendance, Pastor Marvin L. Winans, great-grandson of my mother’s first pastor, came back to join the Mack Ave. congregation – as he does, on occasion – and sang at her funeral.

The magnificent home that my father bought in Highland Park, where I was raised, and where returned to lived in recent years, burned in a fire in 2007.

Photographer Jacques Demetre is in his nineties, as of 20014, and still living in France. He remembers well his 1959 visit to Joe’s Record Shop in Detroit. The photos that he took became a part of his book with writer Marcel Chauvard, Voyage Au Pay Blues – Land of the Blues – in French and English.

I’m writing a book about my father, and about growing up in the record shop. I have lived all of my life in Highland Park and Detroit, and today, I live in the neighborhood created when Black Bottom was destroyed, within blocks of the place where Joe’s Record Shop on Hastings Street once stood.

Marsha Music, Detroit

[My thanks, especially, to Joe Von Battle Jr. and Darryl Battle, and to the Battle siblings through the years, for sharing their memories; without them my efforts to pay tribute to Joe Von Battle’s legacy would not be possible. Thanks to writers Dave Marsh, Craig Werner and the others who have encouraged me to write and tell my stories, over the years. More recently, many thanks to Paul Vernon, Joe Louis, Stefan Wirtz and members of the Real Blues Forum, on Facebook, for their diligence in tracing the recording history of JVB records and sharing so much information with me. And a thanks to Mr.Dave Usher, a long-time friend of my father and fellow music producer, who came to my father’s aid in his last years.]

No comments:

Post a Comment