BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY Spies of Mississippi tells the story of a secret spy agency formed by the state of Mississippi to preserve segregation and maintain white supremacy. The anti-civil rights organization was hidden in plain sight in an unassuming office in the Mississippi State Capitol. Funded with taxpayer dollars and granted extraordinary latitude to carry out its mission, the Commission evolved from a propaganda machine into a full blown spy operation. How do we know this is true? The Commission itself tells us in more than 146,000 pages of files preserved by the State. This wealth of first person primary historical material guides us through one of the most fascinating and yet little known stories of America's quest for Civil Rights. Written by Dawn Porter

See how a secret Mississippi spy agency sought to preserve segregation during the Civil Rights era.

See how a secret Mississippi spy agency sought to preserve segregation during the Civil Rights era.

The Film

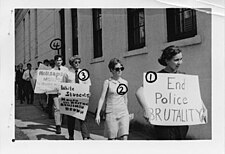

Spies of Mississippi tells the story of a secret spy agency formed by the state of Mississippi to preserve segregation during the 1950s and ‘60s. The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission evolved from a predominantly public relations agency to a full-fledged spy operation, spying on over 87,000 Americans over the course of a decade. The Commission employed a network of investigators and informants, including African Americans, to help infiltrate some of the largest Black organizations — NAACP, CORE, and SNCC. They were granted broad powers to investigate private citizens and organizations, keep secret files, make arrests and compel testimony.

The film reveals the full scope and impact of the Commission, including its links to private White supremacist organizations, its ties to investigative agencies in other states, and even a program to bankroll the opposition to civil rights legislation in Washington D.C.Spies of Mississippi tracks the Commission’s hidden role in many of the most important chapters of the civil rights movement, including the integration of the University of Mississippi, the trial of Medgar Evers, and the KKK murders of three civil rights workers in 1964.

Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission

The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission was a state agency directed by the governor of Mississippi that existed from 1956 to 1977, also known as the Sov-Com.[2] The commission's stated objective was to "[...] protect the sovereignty of the state of Mississippi, and her sister states" from "federal encroachment." Initially, it was formed to coordinate activities to portray the state, and the legal racial segregation enforced by the state, in a more positive light.

During its existence, it profiled over more than 87,000 names of people associated with the civil rights movement, which it opposed, and was complicit in the murders of three civil rights workers.[3]

Creation and structure

The Commission was created by the Mississippi Legislature in 1956 in reaction to the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, in which the Court held that racially segregated public schools were unconstitutional. The "sovereignty" the state was trying to protect was against federal enforcement of civil rights laws, such as the 1964Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, and U.S. Supreme Court rulings. The membership consisted of 12 appointed and legislatively elected members, and the Governor of Mississippi, Lieutenant Governor of Mississippi, the Speaker of the House of Representatives of Mississippi and the Attorney General of Mississippi ex officio. The governor sat as the chairman. Its initial budget was $250,000 a year. The Sovereignty Commission's first investigator was Leonard Hicks who began his position in1956. In 1958 Zack Van Landingham became an investigator, followed by R.C. "Bob" Thomas, Rep. Hugh Boren, Andy Hopkins, and Tom Scarbrough in 1960. Other principal investigators for the Sovereignty Commission were Virgil Downing, Leland Cole, Fulton Tutor, Edgar C. Fortenberry and James "Mack" Mohead.

Activities

As the state's public relations campaign failed to dampen rising civil rights activism, the commission put people to work as a de facto intelligence organization trying to identify those citizens in Mississippi who might be working for civil rights, be allied with communists, or just tipped state surveillance if their associations, activities, and travels did not seem to conform to segregationist norms. Swept up on lists of people under suspicion by such broad criteria were tens of thousands of African-American and white professionals, teachers, and government workers in agricultural and other agencies, churches and community organizations. The "commission penetrated most of the major civil-rights organizations in Mississippi, even planting clerical workers in the offices of activist attorneys. It informed police about planned marches or boycotts and encouraged police harassment of African-Americans who cooperated with civil rights groups. Its agents obstructed voter registration by blacks and harassed African-Americans seeking to attend white schools."[4]

The commission's activities included attempting to preserve the state's segregation and Jim Crow laws, opposing school integration, and ensuring portrayal of the state "in a positive light." Among its first employees were a former FBI agent and a transfer from the state highway patrol. "The agency outwardly extolled racial harmony, but it secretly paid investigators and spies to gather both information and misinformation."[5] Staff of the commission worked closely with, and in some cases funded, the notorious White Citizens' Councils. From 1960 to 1964, it secretly funded the White Citizens Council, a private organization, with $190,000 of state funds.[6]:75 The commission also used its intelligence-gathering capabilities to assist in the defense of Byron De La Beckwith, murderer of Medgar Evers, during his second trial. Sov-Com investigator Andy Hopkins provided De La Beckwith's attorneys with information on the potential jurors, which the attorneys used during the selection process.[6]:204-5

The Sov-Com was also involved in the arrests and murders of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, three volunteers for the Freedom Summer project of 1964.

Demise and legacy

The commission officially closed in 1977, four years after Governor Bill Waller vetoed funding. After the agency was disbanded, state lawmakers ordered the files sealed until 2027 (50 years later). After a lawsuit, in 1989 a federal judge ordered the records opened, with some exceptions for still-living people. Legal challenges delayed the records' availability to the public until March 1998. Once unsealed, records revealed more than 87,000 names of people about whom the state had collected information, or included as "suspects." Today, the records of the commission are available online for search.[7] The records also revealed the state's complicity in the murders of three civil rights workers atPhiladelphia, Mississippi; its investigator A.L. Hopkins passed on information about the workers, including the car license number of a new civil rights worker, to the Commission, which passed the information to the Sheriff of Neshoba County, who was implicated in the murders.[8]

A Louisiana Sovereignty Commission, with a similar mission, existed during the 1960s. For a time it was under the direction of the attorney Frank Voelker, Jr., of Lake Providencein East Carroll Parish, who resigned the post to run for governor of Louisiana in 1963. State legislator Spencer Myrick of Oak Grove in West Carroll Parish was an investigator for the commission, since disbanded.

No comments:

Post a Comment