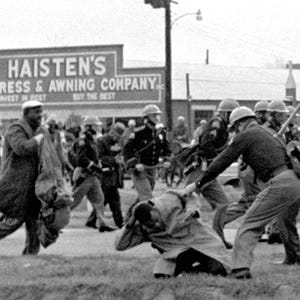

Crowds gathered in Selma, Alabama to remember Bloody Sunday and to hear remarks from President Obama and Rep. John Lewis. VPC

SELMA, Ala. — President Obama, speaking Saturday at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, placed Selma in the pantheon of historical sites alongside Concord, Gettysburg and Kitty Hawk.

Then Obama, joined by his wife Michelle and their daughters, walked hand-in-hand with one of the original Selma marchers, Rep. John, Lewis, D-Ga., across the 1,200-foot-long, steel-and-concrete bridge to commemorate the bloody civil rights confrontation 50 years ago that transformed America. Former President George W. Bush and other dignitaries and activists joined them.

It was a particularly poignant moment for a president who has traced the events on Bloody Sunday in 1965 to raising the nation's conscience and changing its voting laws, opening the way for his election as the country's first African-American president.

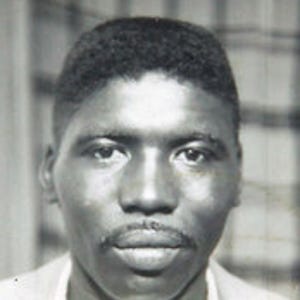

And an especially sweet moment for the 75-year-old Lewis, who suffered a cracked skull five decades ago when Alabama state troopers and Sheriff Jim Clark's posse used billy clubs and tear gas against civil rights activists as they attempted to march to Montgomery to demand the right to vote.

With temperatures heading to the 60s, thousands of people packed downtown Water Street, stretching away from the stage at the bottom of the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

"There are places, and moments in America where this nation's destiny has been decided," Obama told the crowd. "Many are sites of war — Concord and Lexington, Appomattox and Gettysburg. Others are sites that symbolize the daring of America's character — Independence Hall and Seneca Falls, Kitty Hawk and Cape Canaveral. Selma is such a place."

Obama used the very place he stood to underscore the challenge that civil right activists faced five decades ago.

"The Americans who crossed this bridge were not physically imposing," he said. "But they gave courage to millions. They held no elected office. But they led a nation."

"They marched as Americans who had endured hundreds of years of brutal violence, and countless daily indignities — but they didn't seek special treatment, just the equal treatment promised to them almost a century before."

Before his speech, Obama signed legislation awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to these "foot soldiers" of the Selma voting rights demonstrations, including the eventual march to Montgomery that took place March 21-25, 1965.

The president attempted to draw a direct line from the past to the present — and the future — by addressing such sensitive issues as recent racial clashes in Ferguson, Mo., and political disputes over renewing the Voting Rights Act that Selma helped deliver.

He rejected those who argue that there had been little real change in the past 50 years. "To deny this progress, this hard-won progress — our progress — would be to rob us of our own agency, our own capacity, our responsibility to do what we can to make America better." He also rejected the notion that racism in America had been banished. "We just need to open our eyes, and ears, and hearts, to know that this nation's racial history still casts its long shadow upon us."

Instead, he argued, "Selma teaches us, too, that action requires that we shed our cynicism. For when it comes to the pursuit of justice, we can afford neither complacency nor despair."

"Fifty years from Bloody Sunday, our march is not yet finished, but we are getting closer," Obama told the crowd. "Two hundred and thirty-nine years after this nation's founding, our union is not yet perfect, but we are getting closer. Our job's easier because somebody already got us through that first mile. Somebody already got us over that bridge."

In the lead-up to the president's remarks, speakers blared gospel and '60s tunes, while a video board displayed documentary images from the civil rights area, including the replay of a phone conversation between President Lyndon Johnson and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr.

Celebrants snapped pictures of each other or of celebrities in the crowd that included Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton and Martin Luther King III.

Many of the parents and grandparents of people who lined Water Street couldn't vote in some states because of restrictive racial policies; that started to change on March 7, when state troopers attacked marchers on the bridge in Selma, sending more than 50 people to the hospital, but also galvanizing support for the federal Voting Rights Act later that year.

Ron Davis, only 2 years old during the Selma attack, lived to see millions of Americans join the voter rolls — and he grew up to be the two-term mayor of Prichard, Ala.

"You think about what our ancestors did to fight for us," Davis said as he awaited Saturday's events.

Jan Meadows, 73, who traveled from Atlanta to Selma to hear Obama speak, said the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — combined with the Civil Rights Act the year before — "gave us the right to get political power."

That power enabled African Americans to advance economically and socially, said Meadows, who became an architectural interior designer. "We were able to vote, we were able to elect black officials — we were able to go to school," she said.

There are also vast economic problems in Selma and elsewhere. Many boarded-up businesses in Selma's small downtown were decorated for Saturday's ceremony. The area's poverty and jobless rates remain high.

"I'm hoping this will bring on changes, not just in Selma, but in the South," said Annice Jordan, 72, a retiree from Seattle who was born in Selma. "When it comes to poor people, things are sad."

For Sidney Willis. 69, of Mobile, Ala., this is his ninth straight Bloody Sunday commemoration. All these years later, Willis said, the event remains as poignant as ever.

The commemoration helps assuage some of the hurt he felt as a black man coming of age in the South during a tumultuous moment for America, he said.

"I knew what it was to see segregation," Willis said. "When I was In the Coast Guard after high school, there were places the white guys could go that I wouldn't have been allowed to frequent. We've made progress from those days, but we still have a long way to go."

Luci Baines Johnson, the late president's younger daughter, recalled to USA TODAY being by her father's side the day he signed the voting act into law.

"This marks a sacred moment in our history," said Johnson, who traveled to Selma to join in the commemoration. "There were so many heroes that led to this day, the ones whose names we know but also those who were fighting in the shadows and whose names weren't recorded in the history books."

Obama previously took part in the annual commemoration in 2007, when he was serving in the Senate.

The commemoration comes at another difficult period in race relations in America, following the recent high-profile killings by police of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., Eric Garner in Staten Island, N.Y., and Tamir Rice in Cleveland, all black men.

This week, the Justice Department issued a scathing report detailing institutional racism in the Ferguson Police Department, while clearing former police officer Darren Wilson for the shooting last summer of the unarmed 18-year-old Brown, whose killing galvanized nationwide protests. Brown's family announced this week their intention to file a wrongful death lawsuit against Ferguson and Wilson.

"I feel a direct connection to what happened in Selma and wanted to be here," said Gwenn Carr, the mother of Garner, who is taking part in the commemoration. "What happened back then, what's happening today, it's déjà vu."

Over the past two days, at forums and gatherings at some of the same Selma churches that served as the nerve centers of the 1965 movement, civil rights leaders have been calling on Americans to pressure Congress over the passage of stringent voter ID rules and other new voting rules that have been passed in several states after the Supreme Court struck down a key provision in the landmark legislation nearly two years ago.

In what is known as the Shelby ruling, the high court ruled that the Voting Rights Act formula used to determine which parts of the country would need federal approval — known as pre-clearance — to change their voting procedures was outdated. The court instructed Congress to write a formula that was reflective of current conditions, but Congress has yet to act.

"The voting rights act is being dismantled," said Kirsten Moller, who traveled to Selma from San Francisco to be part of the commemoration. "We need to protect it. It's not a given. We need to be vigilant."

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., who was among the dozens of Washington lawmakers to travel to Selma this weekend, called out her fellow lawmakers for failing to taking action on the voting rights, nearly two years after the high court decision.

"We have not in the United States Congress reinvigorated the Voting Rights Act gotten it back to the president for his signature," Warren said. "That's what we should be talking about today."

Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio who was also in Selma Saturday, said the issue should be debated by Congress, but he resisted Democrats efforts to tie on Portman the Bloody Sunday anniversary.

"This about more than tweaks of the Voting Rights Act," he said. "This is about how do we secure that we have equal justice and that we learn from lessons of the past."

Gatrice Benson, a Selma native now living in Georgia, got a call from her 73-year-old grandmother not long after Obama finished his speech.

To bring viewers closer to the events in Selma, USA TODAY is filming in full 360-degree video. In the special player below, explore the celebration in Selma, Ala., by clicking and dragging your mouse to rotate the panorama left or right.

Her grandmother, Mary Martin, tells stories about the flurry of activity around Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in March 1965. The church, not far from her house, was at the center of organizing activity at the time of the voting rights marches. She couldn't join her granddaughter at the foot of the bridge on Saturday, but watched the television coverage.

"When she saw the pictures of Obama crossing the bridge, it was just do powerful," Benson said. "She cried and I cried, too."

Eric Archie, 52, a construction manager from Montgomery, called the event "a celebration for me ... Something that divided us is now unifying,"

Archie brought his 8-year-old son Amari, who he said became interested in history after seeing the film Selma.

"I want him to see Selma," Archie said. "Maybe 50 years from now, he can tell his children he was at the 50th anniversary."

No comments:

Post a Comment