BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY Black Diggers - Indigenous Australians and World War One

Transcript of "Black Diggers - Indigenous Australians and World War One"

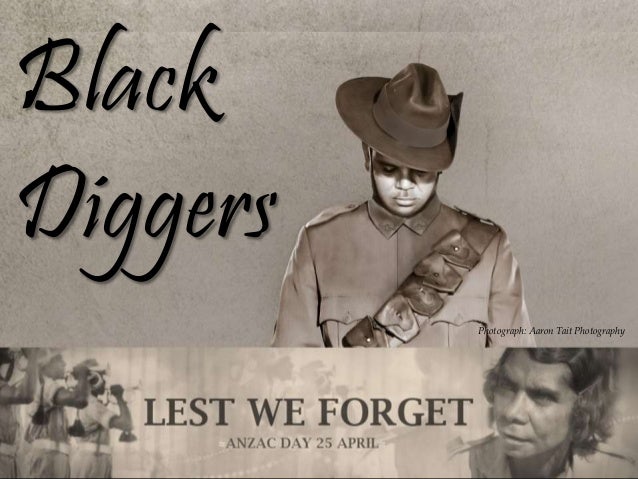

- 1. Black Diggers Photograph: Aaron Tait Photography

- 2. Black Diggers NOTE: In respect to the customs of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander reader images/photographs have been blurred. To see full images/photographs click on each image/photograph to reveal that image/photograph. WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following PowerPoint contains images of deceased persons. NOTE: When on a slide with a blurred image/photograph and you don’t want the image/photograph to be revealed then to go on to the NEXT slide please by selecting the ARROW BUTTON (as shown here) on the slide rather than the ARROW on the keyboard.

- 3. Black Diggers a play written by Tom Wright and directed by Wesley Enoch Black Diggers: challenging Anzac myths by Paul Daley – The Guardian – 14th January, 2014 “Hundreds of Indigenous servicemen fought for the British empire in the first world war – but are forgotten by many. A new play aims to challenge the cultural caricature of the Anzac digger. A century after the first world war, Australia has come to eulogise its Anzac diggers for their supposedly unique capacity for mateship, resilience, egalitarianism and sacrifice. In the broad Australian consciousness, they have also been defined as white and of European Christian extraction – the son or grandson of pioneers, or perhaps even a migrant from the old country. But like so much about the clichéd Australian Anzac, this entrenched cultural caricature overlooks the extraordinary experiences of minorities who fought as Australian sons of the empire – not least those of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.”

- 4. “Aussie” Caricatures

- 5. Black Diggers a play written by Tom Wright and directed by Wesley Enoch Now a new play about their experiences is opening at the Sydney festival. Directed by Wesley Enoch and written by Tom Wright, Black Diggers draws on both traditional archival materials – letters and diaries – of Indigenous soldiers, and a rich vein of oral histories about the servicemen told through the generations. According to the Australian War Memorial, more than 400 Indigenous Australians fought for the British empire in the first world war. This is probably a conservative estimate: thanks to curious Commonwealth rules about who was eligible to fight – Indigenous volunteers had to prove to recruiting officers that they were, despite appearances, of “substantially European descent” in order to be considered for enlistment – the actual number of Indigenous men who served in that war will remain the source of conjecture. In late 1914 and 1915, when the first of some 420,000 Australians signed up – 39% of the males aged 18 to 44 from a total population of 4m – Indigenous applicants were often rejected. Then, after the tragic folly of Gallipoli in which 7,600 Australians were killed came the catastrophe of the European western front where 50,000 more perished. As domestic Australian support for the war waned, recruitment officers became colour blind. Full Version: Black Diggers: Challenging Anzac Myths - Paul Daley - The Guardian 14/01/2014

- 6. Why did they join? Indigenous: Australians at War by Garth O’Connell “That is not an easy question to answer of course, as we today are not in the same situation. At the time of WW1, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were not officially classified as citizens of Australia. Under the Protectors' Acts they could not enter a public bar, vote, marry non-Aboriginal partners or buy property. They would have been like every other adventurous young Australian male, wanting to go out and see the world, get paid really good money, see some action and “be home before Christmas”. But these boys stood out in the crowd, they were Aboriginal. They put up with racist slurs and attitudes almost daily in their civilian life - but to their mates in the trenches they were Mick, Ben and Harry. The misconceptions and negative stereotypes that surely many non- Aboriginal diggers had in their minds when they joined would have quickly disappeared when they were living, eating, laughing and dying with these young fellas. But the most tragic aspect of their service was not in them 'going over the top' and running at machine guns and dying - it came after they returned to their country. When they came back home to Australia they were shunned, their sacrifices ignored and their families oppressed even further by their respective State and Federal governments with such cruel initiatives as the "Soldier Settlement Scheme", which appropriated land not available to

- 7. Why did they join? Indigenous: Australians at War by Garth O’Connell pub, there was no Government support for the wounded or mentally scarred Indigenous veterans, and their children were being removed... The service that these warriors did for an ungrateful nation helped provide momentum to the growing Aboriginal Rights Movement in the 1930's. They provided hard evidence that they, as a people, were willing to serve Australia for the better, but at the time, white Australia was not willing to help them get on with life. Even though their small number (estimated to be 500-600) seems like a drop in the bucket of the tens of thousands of other Australians who served in World War One, their significance to modern Aboriginal history is immense. Today the bodies of those that fell in the battlefields of France and Belgium remain with their mates, thousands of miles away from their ancestral homes.” Why did they join? Garth O'Connell - Indigenous: Australians at War (Website)

- 8. Private Douglas Grant Private Douglas Grant originally enlisted in the AIF in 1916, but was discharged because he was Aboriginal. He later successfully re- enlisted and was captured in France in 1917, drawing the interest of German scientists and anthropologists as a prisoner of war. He was a talented artist and admired by his fellow POWs for “his honesty, his quick mind, and because he was so aggressively Australian.”

- 9. Private Douglas Grant One of the characters is based on Aboriginal Douglas Grant, who was orphaned as a boy and adopted by Robert Grant, a Scottish taxidermist and anthropologist who worked for the Australian Museum, and raised with his other son Henry in Sydney. Douglas Grant’s natural parents died either in a tribal battle or in a massacre committed by white pastoral settlers (recent evidence strongly suggests the latter) near the Bellenden Ker Ranges in Queensland when he was a boy. Grant was well educated, spoke – like his father and brother – with a Scottish accent, and worked before the war as a draughtsman. He enlisted in the 34th Battalion in 1916 and was wounded and captured during the 1st battle of Bullecourt in April 1917. The Germans imprisoned him for the rest of the war in Berlin, where he was kept with other dark-skinned soldiers of the empire, from India and Africa. Acting as a go-between for the Red Cross and other prisoners, Grant became such a curiosity to the German authorities that the sculptor Rudolph Markoeser carved his bust in ebony.

- 10. Private Douglas Grant He was also something of a celebrity on his return to Australia, with his own radio show in Lithgow for a while, and often spoke publicly on a diverse range of subjects, including Shakespeare. But he didn’t cope with the transition back to civilian life, drinking heavily and living the later part of his life at the Callan Park mental asylum (where he also worked as a clerk) and the Salvation Army’s men’s quarters. He died in 1951. “He was a fascinating human being, but when he returned to Australia, Douglas Grant really failed to find his place,” Enoch says. “You are left with the impression that he was very disappointed with what he thought was going to happen in his life and what actually eventuated.” Extracts from: Black Diggers: challenging Anzac myths Paul Daley - The Guardian 14/01/2014

- 11. BlackDiggers An Aboriginal soldier (front row, centre) with fellow members of the 3rd Tunnelling Company, AIF, in France in 1917. FACT: “Indigenous Australians in the First World War served on equal terms but after the war, in areas such as education, employment, and civil liberties, Aboriginal ex- servicemen and women found that discrimination remained or, indeed, had worsened during the war period.”

- 12. BlackDiggers An unidentified Indigenous soldier. FACT: “When war broke out in 1914, many Indigenous Australians who tried to enlist were rejected on the grounds of race; others slipped through the net. By October 1917, when recruits were harder to find and one conscription referendum had already been lost, restrictions were cautiously eased. A new Military Order stated: "Half-castes may be enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force provided that the examining Medical Officers are satisfied that one of the parents is of European origin.“ This was as far as Australia – officially – would go.”

- 13. BlackDiggers Private Leonard Charles Lovett, a drover who enlisted and served with the 39th Battalion of the AIF. Fact: “Over 400 Indigenous Australians fought in the First World War. They came from a section of society with few rights, low wages, and poor living conditions. Most Indigenous Australians could not vote and none were counted in the census. But once in the AIF, they were treated as equals. They were paid the same as other soldiers and generally accepted without prejudice.”

- 14. BlackDiggers It’s believed Private Richard Martin lied about his place of birth, stating he was from New Zealand when he enlisted in December 1914 in order to avoid rejection based on his race. He was wounded in action three times before being killed in March 1918. Fact: “Loyalty and patriotism may have encouraged Indigenous Australians to enlist. Some saw it as a chance to prove themselves the equal of Europeans or to push for better treatment after the war. For many Australians in 1914 the offer of 6 shillings a day for a trip overseas was simply too good to miss.”

- 15. BlackDiggers Private Alfred Jackson Coombs (front row, centre) served at Gallipoli in the Australian Heavy Battery.

- 16. BlackDiggers The 35th Battalion formed in Newcastle, NSW, in 1915 was dubbed “Newcastle’s Own”. The Indigenous serviceman on the right is believed to be Private Thomas James Walker. The battalion fought at Passchendaele, and only 90 of the 508 who went into battle came out unwounded.

- 17. BlackDiggers Private Harold Arthur Cowan, also known as Arthur Williams, pictured with his cousin Hazel Williams and her baby sister after he had enlisted in NSW in 1917. Before serving in the 6th Light Horse Regiment, Arthur was a well known boxer and played representative football. Fact: “Only one Indigenous Australian is known to have received land under a "soldier settlement" scheme, despite the fact that much of the best farming land in Aboriginal reserves was confiscated for soldier settlement blocks.”

- 18. BlackDiggers Trooper William Allen, who served in the 11th Light Horse Regiment, with his wife on their wedding day in 1918. Fact: "It was only in May 1917 that an army order allowed the enlistment of 'half-castes' due to the shortage of volunteers and the carnage on the Western Front,"

- 19. BlackDiggers Private Alfred John Henry Lovett with his wife Sarah and two sons before leaving Australia in October 1915. He survived the war and returned home in March 1918. Fact: “Generally, Indigenous Australians have served in ordinary units with the same conditions of service as other members. Many experienced equal treatment for the first time in their lives in the army or other services. However, upon return to civilian life, many also found they were treated with the same prejudice and discrimination as before.”

- 20. BlackDiggers Lance Corporal Charles Tednee Blackman served in the 9th Battalion, and in February 1918 wrote to his friend and former employer J. H. Salter that his fellow soldiers “treated me [as] good pals would.” He embarked on 21st October 1915 and was one of the earliest known aboriginal soldiers to enlist. Fact: “Even though many were denied basic freedoms and other citizenship rights it's now estimated that a thousand Aboriginal men served in the First World War - from Gallipoli to the Light Horse in Egypt and the Australian Tunnelling Company on the Western Front.”

- 21. BlackDiggers Trooper Horace Thomas Dalton served with the 11th Light Horse Regiment from May 1918, and returned to Australia in July 1919. Fact: “Some might find it strange that Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders wanted to serve a country that did not recognise them as citizens (until 1967). Reasons for enlistment were many: some hoped that war service might help the Indigenous campaign for citizenship and equality; some believed the war was just; others sought adventure, good pay, or joined up because mates did.”

- 22. BlackDiggers Private Harry C Murray of the 11th Light Horse Regiment left Australia in December 1917 and returned home July 1919. Fact: “In common with other soldiers, Indigenous servicemen generally were anonymous men who earned neither bravery awards nor mentions in the official history. However, some were decorated for outstanding actions. Corporal Albert Knight, 43rd Battalion, and Private William Irwin, 33rd Battalion, were each awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal – second only to the Victoria Cross for men in their ranks – and others the Military Medal. killed in action the following year.”

- 23. BlackDiggers An unidentified Aboriginal soldier, photographed in England in 1918. Fact: “Indigenous soldiers were paid the same amount as their European counterparts, and accepted as “one of the boys” by most. Unfortunately, this didn’t result in improved treatment in Australian society as a whole.”

- 24. BlackDiggers Private Gilbert Williams was discharged from the AIF in 1917 after being found “medically unfit for further service” - according to his family, it was due to the colour of his skin. Fact: “Indigenous Australians were present in almost every Australian campaign of World War I. In the heat of battle, survival could come down to relying on your mates so racism, for once, took a back seat. White and black soldiers forged friendships in the trenches of Gallipoli and the Western Front or on horseback with the Light Horse in the Middle East.”

- 25. BlackDiggers Private Miller Mack of the 50th Battalion served in France and contracted bronchial pneumonia in 1917. He was evacuated to England before returning to Australia in September 1917. He died of his illness two years later, in September 1919. Fact: “Aboriginal land was confiscated to be given to ex-servicemen as part of the “soldier settlement” scheme.”

- 26. BlackDiggers Trooper Fisher was an Aboriginal serviceman who was born at Claremont in Queensland but who lived at the Barambah Settlement (renamed Cherbourg Aboriginal Settlement in 1931). He enlisted in Brisbane on 16 August 1917 in the 28th Reinforcements to the 11th Light Horse Regiment and embarked in Sydney on the troopship Ulysses on 19 December 1917. After landing at Suez, he was transferred to the 4th Light Horse Training Regiment at Moascar, Egypt, and eventually to the 11th Light Horse Regiment on 13 April 1918. Trooper Fisher returned to Australia on the troopship Morvada which sailed from Kantara on 20 July 1919. Frank Fisher is the great- grandfather of the Olympic gold medallist Catherine Freeman. He returned to Australia in July 1919 and became a famous rugby league player, dubbed King Fisher. (courtesy : Australian War Memorial, Donor: D. Huggonson)

- 27. BlackDiggers Corporal Harry Thorpe, from Lake Tyers Mission Station in Victoria, enlisted in 1916 and fought first in France and then in Belgium, where he was noticed for his courage and leadership. He was promoted to Corporal and awarded the Military Medal. He was shot in August 1918 in France and died soon after. Fact: “In 1909, the Defence Act 1909 (Cwlth) prevented those who were not of 'substantially European descent' from being able to enlist in any of the armed forces.”

- 28. 18 Powerful Photos Of The Forgotten Indigenous Soldiers Of World War I Australian War Memorial: Indigenous Australian Servicemen Black Diggers: challenging Anzac myths Indigenous Australians at War Indigenous Australians at War We will remember them Webography and Sources Assembled: A. Ballas

No comments:

Post a Comment