BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY Murder of Louis Allen

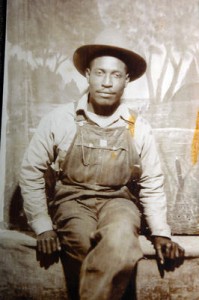

| Louis Allen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 25, 1919 Amite County, MississippiU.S. |

| Died | January 31, 1964 (aged 44) Amite County, MississippiU.S. |

Cause of death

| Murder |

| Ethnicity | African American |

| Occupation | Businessman |

Louis Allen (April 25, 1919 – January 31, 1964) was an African-American resident and married businessman with a family inLiberty, Mississippi; he was shot and killed on his land during the civil rights era after trying to register to vote and being suspected of talking to federal officials about the 1961 murder of Henry Lee by a white state legislator.

Since the late 20th century, the case has been investigated by a history professor at Tulane University, by the FBI beginning in 2007 as part of its review of civil rights-era cold cases, and in 2011 by CBS 60 Minutes; all point to Allen's having been killed by Daniel Jones, then the county sheriff. No one has been prosecuted for the murder.[1] Allen was among a dozen witnesses of the murder of Herbert Lee by E.H. Hurst, a white state legislator, in September 1961. Civil rights activists had come to Liberty that summer to organize for voter registration; essentially no black had been allowed to vote since 1890, when the state disfranchising constitution was passed.

Early life

Louis Allen was a native of Amite County, Mississippi, where he was born in 1919. The population was majority black, with an economy based on agriculture: cotton, dairy farming and logging. Many blacks left before World War II because of the poor economic opportunities and social oppression under Jim Crow. Population declined by 29% from 1940 to 1960, following earlier declines. In the first half of the 20th century, more than six million blacks left the South in the Great Migration to the North, Midwest, and, beginning in the 1940's, West Coast in search of jobs and better living conditions.

Allen served in the United States Army during World War II; he enlisted at age 24 in the service at Camp Shelby, Mississippi on January 12, 1943.[2] After his return, Allen worked as a logger and farm laborer. Allen and his wife Elizabeth had four children together, including a daughter and a son Henry (called Hank). He built up his own logging business, doing well enough also to buy his own land. There he and his family raised some produce and dairy cows.

Murder of Herbert Lee

Mississippi's constitution of 1890 politically disfranchised African-Americans, using provisions such as poll taxes, literacy tests, andgrandfather clauses to exclude them from voting.[3] In the early 1960s, a local chapter of the NAACP was founded by E.W. Steptoe for the purpose of registering black voters. He was soon joined by Robert Parris Moses of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In August 1961, Moses filed charges against Billy Jack Caston, cousin to Sheriff Daniel Jones and son-in-law of pro-segregation state legislator E. H. Hurst, for an assault against him and other civil rights activists by a white mob. It was the first time that an African American had legally challenged white violence in Amite County.[4] The white jury acquitted Caston and Moses was escorted to the county line, ostensibly for his own safety. Moses left the county in January 1962.[4] Steptoe consulted with Justice Department agents in Jackson about intimidation tactics used by Hurst and other prominent whites in Liberty.[3]

On September 25, 1961, Hurst followed an NAACP member named Herbert Lee to the Westbrook Cotton Gin, where he shot and killed the activist. Louis Allen and eleven other men witnessed the murder.[5] When a coroner's inquest was conducted hours later, in a courtroom filled with armed white men, Allen and the other witnesses were pressured into giving false testimony. They supported Hurst's claim of shooting Lee in self-defense, leading Hurst to be cleared of any wrongdoing.[5] However, Allen later told fellow activists the truth behind Lee's killing. Allen discussed the incident with Julian Bond, who encouraged him to tell his story to federal authorities. Bond was aware that, in the racially charged atmosphere of Amite County, Allen was at high personal risk if this became known. Interviewed in 2011 for a CBS 60 Minutes segment on Allen's murder, Bond said:

Learning that a federal jury was to consider charges against Hurst, Allen talked to the FBI and the United States Commission on Civil Rights in Jackson and asked for protection if he testified. An FBI memo reported that he "expressed fear that he might be killed", but the Justice Department said it could not give him protection.[1] Allen chose to repeat the official version of events which exonerated Hurst.

Harassment and murder of Louis Allen

Although Allen had not cooperated with the Justice Department, rumors of his visit in Jackson quickly spread amongst Liberty's white community. Local whites blackballed Allen and cut off customers for his logging business. In August 1962, as Allen and two other black men tried to register to vote at Amite County Courthouse, they were shot at by an unknown assailant.[5] (No black had been allowed to vote in Amite County since 1890.)[6] Following this incident, a white businessman threatened Allen, saying, "Louis, the best thing you can do is leave. Your little family—they're innocent people—and your house could get burned down. All of you could get killed."[5] When Allen reported the death threats, the FBI – which had limited jurisdiction over civil rights cases at the time – referred the matter to the Amite County sheriff's office. The FBI did so despite an agent acknowledging in a 1961 memo that, "Allen was to be killed and the local sheriff was involved in the plot to kill him."[1]

Allen allegedly became a target of harassment by Amite County Sheriff Daniel Jones. In a later interview, Allen's son, Hank, described Jones as "mean", recounting how Jones arrested his father on trumped-up charges and beat him outside his home. On one such occasion in September 1962, Jones brokes Allen's jawbone with a flashlight. Moses wrote to Assistant Attorney General John Doar about Allen: "They're after him in Amite [County]," it [the letter] says, and makes reference to "a plot by the sheriff and seven other men."[1] Jones' father was a high-ranking "Exalted Cyclops" in Liberty's chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. FBI documentation from the 1960s claimed that Daniel Jones was also a Klan member.[1]

When he got out of jail, Allen filed an assault complaint with the FBI against Jones. He summarily testified before an all-white federal grand jury. As blacks had been prevented from registering and voting, they could not serve on juries. The jury dismissed his complaint.[1] Allen stayed in Liberty because he was caring for his elderly parents.[7] Among Allen's associates was Leo McKnight, who had worked with him and twice tried to register to vote with him. In February 1963 McKnight and his family: wife, pregnant daughter, and son-in-law, died in a suspicious fire at their house. Blacks believe they were murdered.[5] In November 1963, Jones arrested Allen again, falsely charging him for bouncing a check and having a concealed weapon. Law enforcement officials threatened him with 3 to 5 years in the penitentiary; after three weeks, the NAACP raised the bail for him.[5]

Allen's mother died and, in January 1964 Allen arranged to leave Liberty and move in with his brother in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as he feared for his life.[7] On January 31, 1964, the night before his planned departure, Allen was ambushed at the cattle grid at the border of his property. He was killed by two shotgun blasts to the head. His body was found by his son Henry (called Hank).[5] Interviewed by CBS 60 Minutes in 2011, Hank Allen said, "He [Sheriff Daniel Jones] told my mom that if Louis had just shut his mouth, that he wouldn't be layin' there on the ground. He wouldn't be dead."[1]

Investigations

No thorough investigation into Allen's murder was conducted until 1994. That year, Plater Robinson, a history professor at Tulane University, began examining the case files. Robinson's research in the following years pointed to county sheriff Daniel Jones as a likely suspect in the killing. In 1998, Robinson conducted a tape-recorded interview with Alfred Knox, an elderly black preacher in Liberty. Knox said that Jones had recruited his son-in-law, Archie Weatherspoon, to "kill Louis Allen". When Weatherspoon refused Jones' request to "pull the trigger", Jones allegedly killed Allen himself. Both Knox and Weatherspoon are since deceased.[1]

In 2007, the FBI reopened Allen's case as one of a number of civil rights-era cold cases it was examining. Its staff identified Jones as the prime suspect. As of 2011, the FBI has been unable to collect enough evidence to prosecute.[1] In April 2011, the CBS newsmagazine 60 Minutes broadcast a report about the Allen case. Correspondent Steve Krofthad traveled to Liberty to interview local residents about the case. He was largely met with silence. Kroft interviewed former sheriff Daniel Jones on his property; the elderly man denied killing Allen, and he invoked the Fifth Amendment when asked about his alleged Klan membership.[1]

Legacy and honors

- Bertha Gober's song, "We'll Never Turn Back," memorialized Lee's murder.[8]

- Lee's son, Herbert Lee, Jr., became active at age 15 in the civil rights movement in 1965.

- The Westbrook Cotton Gin was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010. Its significance as the site of Lee's murder by a white man during the Civil Rights era was part of the reason that it was nominated.

No comments:

Post a Comment