BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY

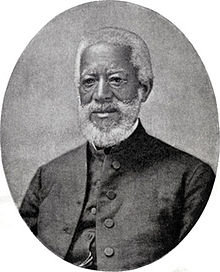

Alexander Crummell

| Alexander Crummell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 3, 1819 New York City, New York |

| Died | September 10, 1898 (aged 79) Red Bank, New Jersey |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Queens' College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Priest, Professor |

Alexander Crummell (March 3, 1819 - September 10, 1898) was a pioneering African-American priest, professor and African nationalist. Ordained as an Episcopal priest in the United States, Crummell went to England in the late 1840s to raise money for his church by lecturing about American slavery. Abolitionists supported his three years of study at Cambridge, where Crummell developed concepts of pan-Africanism.

In 1853 Crummell moved to Liberia, where he worked to convert native Africans to Christianity and educate them, as well as to persuade American colonists of his ideas. He wanted to attract American blacks to Africa on a colonial, civilizing mission. Crummell lived and worked for 20 years in Liberia and appealed to American blacks to join him, but did not gather wide support for his ideas.

After returning to the United States in 1872, Crummell was called to St. Mary's Episcopal Mission in Washington, DC. In 1875 he and his congregation founded St. Luke's Episcopal Church, the first independent black Episcopal church in the city. They built a new church on 15th Street, NW, beginning in 1876, and celebrated their first Thanksgiving there in 1879. Crummell served a rector there until his retirement in 1894. The church was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

Early life and education

Crummell was born in New York City to Charity Hicks, a free woman of color, and Boston Crummell, a former slave. According to Crummell's own account, his paternal grandfather was an ethnic Temne born in Sierra Leone, who was captured into slavery when he was around 13 years old.[1] Both parents were active abolitionists, and allowed their home to be used to publish the first African American newspaper, Freedom's Journal. Boston Crummell instilled in his son a sense of unity with Africans living in Africa. His parents' influence and these early experiences within the abolitionist movement shaped Crummell’s values, beliefs, and actions throughout the rest of his life. For example, even as a boy in New York, Crummell worked for the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Crummell began his formal education in the African Free School No. 2 and at home with private tutors. Other African-American men who became active in the abolitionist movement, such as James McCune Smith (a pioneering doctor) and Henry Highland Garnet, also graduated from the school, forming a brilliant generation. Crummell attended the Canal Street High School. After graduating, Crummell and his friend Garnet attended the Noyes Academy in New Hampshire. However, a mob opposed to the new black first-year students attacked and destroyed the school. Crummell next enrolled in the Oneida Institute in central New York, established originally for the education of Native Americans. While there, Crummell decided to become an Episcopal priest. His prominence as a young intellectual earned him a spot as keynote speaker at the anti-slavery New York State Convention of Negroes when it met in Albany in 1840.[2]

Denied admission to the General Theological Seminary in New York City because of his race, Crummell went on to study and receive holy orders; he was ordained in 1842 in Massachusetts. As he struggled against ambivalence and low church attendance, Crummell took a trip to Philadelphia to petition the area bishop for a larger congregation, as Philadelphia had a large free black community. Bishop Onderdonk replied, "I will receive you into this diocese on one condition: No negro priest can sit in my church conventionand no negro church must ask for representation there." Crummell is said to have paused for a moment, and then said, "I will never enter your diocese on such terms."[3]

Career

In 1847, Crummell traveled to England to raise money for his congregation at the Church of the Messiah. While there, Crummell preached, spoke about abolitionism in the United States, and raised almost $2,000. From 1849 to 1853, Crummell studied at Queens' College, Cambridge, sponsored by Benjamin Brodie, William Wilberforce, Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, James Anthony Froude, and Thomas Babington Macaulay.[4][5] Although Crummell had to take his finals twice to receive his degree, he became the first officially black student recorded in the university records as graduated.[6]

During his time at Cambridge, Crummell continued to travel around Britain and speak out about slavery and the plight of black people. During this period, Crummmell formulated the concept of Pan-Africanism, which became his central belief for the advancement of theAfrican race. Crummell believed that in order to achieve their potential, the African race as a whole, including those in the Americas, theWest Indies, and Africa, needed to unify under the banner of race. To Crummell, racial solidarity could solve slavery, discrimination, and continued attacks on the African race. He decided to move to Africa to spread his message.

Crummell arrived in Liberia in 1853, at the point in that country's history when Americo-Liberians had begun to govern the former colony for free American blacks. Crummell came as a missionary of the American Episcopal Church, with the stated aim of converting the native Africans. Though Crummell had previously opposed colonization, his experiences in Liberia changed his mind (see Civilizing mission). Crummell began to preach that "enlightened," or Christianized, ethnic Africans in the United States and the West Indies had a duty to go to Africa. There, they would help civilize and Christianize the continent. When enough native Africans had been converted, they would take over converting the rest of the population, while those from the western hemisphere would work to educate the people and run a republican government. Crummell influenced Liberian intellectual and religious life, as preacher, prophet, social analyst, and educationist, proclaiming a special place for Africa, with its God-given moral and religious potential, in the history of redemption.[7] But, Crummell’s grand scheme was never realized. Most American blacks were more interested in gaining equal rights in the United States than going to colonize or convert Africans. While Crummell successfully served as both a pastor and professor in Liberia, he could not create the society he envisioned. In 1873, fearing his life was in danger from the mulatto ascendancy, Crummell returned to the United States.[7]

There he was called as pastor for St. Mary’s Episcopal Mission in the Foggy Bottom area of Washington, DC, then an African-American neighborhood. In 1875 he and his congregation founded St. Luke's Episcopal Church, the first independent black Episcopal church in the city. They raised the money to construct a new church on upper 15th Street, N.W., in the Columbia Heights area, beginning in 1876, and celebrated Thanksgiving in 1879 in it. Crummell served as rector at St. Luke's until his retirement in 1894. The church was designated aNational Historic Landmark in 1976.[8] Crummell taught at Howard University from 1895 to 1897.[7]

Despite frustrations, Crummell never stopped working for the racial solidarity he had advocated for so long. Throughout his life, Crummell worked for black nationalism, self-help, and separate economic development. He spent the last years of his life setting up the American Negro Academy, an organization to support African-American scholars, which opened in 1897.[9] Alexander Crummell died in Red Bank, New Jersey in 1898.

Influence

Crummell was an important voice within the abolition movement and a leader of the Pan-African ideology. Crummell's legacy can be seen not in his personal achievements, but in the influence he exerted on other black nationalists and Pan-Africanists, such as Marcus Garvey, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and W. E. B. Du Bois. Du Bois paid tribute to Crummell with a memorable essay entitled "Of Alexander Crummell," collected in his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk.

In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Alexander Crummell on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[10]

Legacy and honors

Reverend Crummell's private papers are held by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, of the New York Public Library in Harlem.[9] The Alexander Crummell School in Washington, D.C. was named after him.[11]

Veneration

Crummell is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on September 10.[12]

No comments:

Post a Comment