BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY

Marikana killings

Marikana massacre, Lonmin Strike

Lonmin-platinummyn, a, Marikana, Noordwes.jpg

The EPC section of Lonmin Platinum, with Bapong in the foreground

Location Marikana area, close to Rustenburg, South Africa

Participants Independent striking miners

National Union of Mineworkers

Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union

South African Police Service

Mine security

Lonmin

Deaths 14 August: 2

12–14 August: approx. 8 (police: 2, miners: 4, security guards: 2)[1][2]

16 August: 34 miners (78 miners wounded)

Later before resolution: 2

After 18 September resolution: 1[3]

Total:47

Marikana is located in South Africa MarikanaMarikana

Marikana in South Africa

The Marikana massacre[4] was the single most lethal use of force by South African security forces against civilians since 1960.[5] The shootings have been described as a massacre in the South African media and have been compared to the Sharpeville massacre in 1960.[6][7] The incident also took place on the 25-year anniversary of a nationwide South African miners' strike.[8]

Controversy emerged after it was discovered that most of the victims were shot in the back,[9][10] and many victims were shot far from police lines.[11] On 18 September, a mediator announced a resolution to the conflict, stating the striking miners had accepted a 22% pay rise, a one-off payment of 2,000 rand and would return to work 20 September.

The strike is considered a seminal event in modern South African history, and was followed by similar strikes at other mines across South Africa,[12][13] events which collectively made 2012 the most protest-filled year in the country since the end of apartheid.[14]

The Marikana massacre started as a wildcat strike at a mine owned by Lonmin in the Marikana area, close to Rustenburg, South Africa in 2012. The event garnered international attention following a series of violent incidents between the South African Police Service, Lonmin security and the leadership of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) on the one side and strikers themselves on the other, which resulted in the deaths of 44 people, 41 of whom were striking mineworkers killed by police. Also, during the same incident, at least 78 additional workers were injured. The total number of injuries during the strike remains unknown. In response to the Lonmin strikers, there were a wave of wildcat strikes across the South African mining sector.[15]

The first incidents of violence were reported to have started on 11 August after NUM leaders opened fire on NUM members who were on strike. Initial reports indicated that it was widely believed that two strikers died[16] that day; however, it later turned out that two strikers were seriously wounded, but not killed, in the shooting by NUM members.[17] This violence was followed by the death of another eight strikers, police and security personnel who were killed in the following three days.[18][19]

Contents

1 Background

2 First protests

3 Prior peaceful protests and fatal clashes

4 The 16 August massacre

4.1 Preliminary theories

4.2 Protester accounts

4.3 Police accounts

4.4 Eyewitness and journalist accounts

5 Following protests

6 Other protests

7 Arrests

8 Mediation

9 Legal issues

9.1 Official inquiry

10 General reactions

11 Reactions to the shooting

11.1 South Africa

11.1.1 Government

11.1.2 Opposition parties and politicians outside of the government

11.1.3 Trade unions

11.1.4 Mine owner

11.1.5 Strikers' families

11.1.6 Religious leaders

11.1.7 Other

11.2 Media

11.3 International

12 Reactions to the resolution

13 Literature

Background

The Bench Marks Foundation argued: "The benefits of mining are not reaching the workers or the surrounding communities. Lack of employment opportunities for local youth, squalid living conditions, unemployment and growing inequalities contribute to this mess."[20] It claimed the workers were exploited and this was a motivation for the violence. It also criticised the high profits when compared with the low wages of the workers. The International Labour Organisation criticised the condition of the miners saying they are exposed to "a variety of safety hazards: falling rocks, exposure to dust, intensive noise, fumes and high temperatures, among others."[21] Trade and Industry Minister Rob Davies described[when?] the conditions in the mines as "appalling" and said the owners who "make millions" had questions to answer about how they treat their workers.[22] It was later reported by Al Jazeera that the conditions in the mine led to "seething tensions" as a result of "dire living conditions, union rivalry, and company disinterest."[23]

Average price of platinum from 1992 to 2012 in US$ per troy ounce (~$20/g)[24]

Platinum is the main metal exploited in the Marikana mine.[25]

First protests

On 10 August 2012, rock drillers initiated a wildcat strike[26] in pursuit of a pay raise to 12,500 South African rand per month, a figure which amounted to tripling of their monthly salaries (from approx. US$500 to $1,500).[27][28]

The strike occurred against a backdrop of antagonism and violence between the African National Congress-allied National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and its emerging rival, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU). According to a Guardian columnist, the NUM was closely linked to the ruling ANC party but lost its organisational rights at the mine after its membership dropped from 66% to 49% and its leadership began to be seen as 'too close' to management.[29]

Prior peaceful protests and fatal clashes

At the Marikana platinum mine, operated by Lonmin at Nkaneng near Rustenburg, 3,000 workers walked off the job on 10 August after Lonmin failed to meet with workers.[18] On 11 August, NUM leaders allegedly opened fire on striking NUM members who were marching to their offices.[16][30][31] The killing of two miners was reported in the South African media as a central reason for the breakdown in trust within the union amongst workers.[32][33] Despite earlier contradictory reports, the clashes on the 11th are now acknowledged to be the first incidents of violence during the strike.[34]

Between 12 and 14 August, approximately nine people were killed in the area around Marikana. There are conflicting reports on who killed whom during these dates. However, at least four miners, two police officers, and two security guards seem to have been killed during this time.[35][36][37] During the Farlam Commission, the advocate for AMCU accused Lonmin of conspiring with police in killing two miners during a march back from Lonmin offices on 13 August, after which two police officers were also killed.[19]

Before the shootings, SAPS Captain Dennis Adriao told journalists: "We have tried over a number of days to negotiate with the leaders and with the gathering here at the mine, our objective is to get the people to surrender their weapons and to disperse peacefully."[38] However, submissions to the Farlam Commission dispute this, accusing police of failing to negotiate with strikers and participating in revenge killings.[39][40]

The Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union's Joseph Matunjwa said that the protests were in response to poor pay: "As long as bosses and senior management are getting fat cheques, that's good for them. And these workers are subjected to poverty for life. [After] 18 years of democracy, the mineworker is still earning 3,000 [South African Rand – approximately $360] under those harsh conditions underground."[41]

The 16 August massacre

On the afternoon of 16 August, members of a contingent of the South African Police Service, from an elite special unit,[42] opened fire with submachine guns (R5 rifles), on a group of strikers. Within minutes 34 miners were killed, and at least 78 were wounded.[43] The incident was the single most lethal use of force by South African security forces against civilians since the Sharpeville massacre during the apartheid era.[5]

Preliminary theories

Footage from several different angles shows that the police were pushing the strikers into a small area.[original research?] Groups of strikers began singing struggle songs, and marched along police lines. The police fired teargas and rubber bullets into these groups. At least one person in one group shot a handgun at the police. Members of this group either panicked or deliberately charged at a police line which sparked off the shooting.[44]

Protester accounts

[icon] This section requires expansion. (January 2014)

A year after the incident, review of the police reaction indicated:[45]

"Perhaps the most important lesson of Marikana is that the state can gun down dozens of black workers with little or no backlash from 'civil society', the judicial system or from within the institutions that supposedly form the bedrock of democracy. What we have instead is the farcical Farlam commission, an obvious attempt to clear the state's role in the massacre and prevent any sort of real investigation into the actions of the police on that day. In other words, the state can get away with mass murder, with apparent impunity in terms of institutional conceptions of justice and political accountability.

Police accounts

The South African Police Service said that the miners had refused a request to disarm and attacked them with various weapons including firearms taken from the two police officers killed earlier in the week.[46][47] South Africa's Police Commissioner, Mangwashi Victoria Phiyega claimed that the 500 strong police force was attacked by armed strikers, stating "The militant group stormed toward the police firing shots and wielding dangerous weapons."[48]

The day after the shooting Police Commissioner Phiyega released a statement giving a detailed account of the efforts taken by the police to avert the threat of a violent end to the stand-off. In the statement Commissioner Phiyega claims that the SAPS had on a number of occasions since the beginning of the week attempted to negotiate a peaceful end to the strike. Commissioner Phiyega also claims that the SAPS had begun receiving information that the crowd did not intend to leave peacefully and that a violent response from the miners was a likely outcome. At this point Commissioner Phiyega asserts that efforts were made to escalate defensive and crowd control measures by the deployment of concertina wire barricades and the use of water cannons, rubber bullets, stun grenades, and tear gas to break the strikers up and drive them into an area where they could better control them. It was at this point that Commissioner Phiyega claims that the efforts to gain control of the situation failed and the miners turned violent, attacking members of the SAPS. Commissioner Phiyega claims that members of the SAPS who were directly in the path of the attack had moved back in a defensive manner up until the point that it was believed that their safety was under threat, at which point they were cleared to use maximum force to halt the attack and protect themselves. Commissioner Phiyega said that the SAPS had acted well within their legislative mandate as outlined in Section 205 of the Constitution of South Africa.[49]

Advocate Ishmael Semenya, the lawyer for the police during official inquiry described the scale of the shooting when he stated on 6 November 2012 that "No more than 100 police officers discharged their firearms on 16 August. If the commission investigates the lawfulness of police conduct, then we could have to call 100 witnesses."[50]

Eyewitness and journalist accounts

According to the BBC, eyewitnesses reports suggest that "the shooting took place after a group of demonstrators, some holding clubs and machetes, rushed at a line of police officers".[51]

The Times reported that police did not use live ammunition until fired upon by a striking worker with a shotgun, and The Sowetan reported that striking miners appeared to have fired on the police, though the group which advanced towards the police appeared to be "peacefully gathering".[52] The Star journalist Poloko Tau said police maintained that they had been fired on first, but Tau did not see this firsthand.[52]

Siphiwe Sibeko, a Reuters photographer who was present at the scene, stated that he saw at least one of the protesters shoot a pistol before the police opened fire.[53]

Al Jazeera reported that the strikers had been forced by police in armoured vehicles with water cannons into an area surrounded by razor wire at which point the shooting began.[54]

The striking mine workers had gathered on 16 August on nearby Nkaneng Hill armed with spears, pangas (large machete-like knives) and sticks.[28] A large group of women, not employed at the mine, some armed with knobkerries, joined them. Six guns were found at the scene, one of which belonged to a police officer "hacked to death" earlier during the strike.[55]

Greg Marinovich examined the scene and found that the majority of victims were shot 300 meters from police lines where the main "charge" took place.[11] He claims that some of the victims “appear to have been shot at close range or crushed by police vehicles.” Some victims were shot in a "koppie" where they were cornered and could have been arrested. Due to local geography they must have been shot at close range. Few bullets were found in the surrounding area, suggesting they did not die in a hail of bullets. Marinovich concludes that “It is becoming clear to this reporter that heavily armed police hunted down and killed the miners in cold blood.”[9][56]

Following protests

The day after the shootings a group of miners' wives protested singing and chanting slogans and songs from the anti-apartheid struggle. They denied that the striking miners had shot first, insisted that the strike was about wages[citation needed] and demanded that the police officers responsible for the shooting be fired.[57]

Most of the approximately 28,000 employees at the mine did not go to work on Monday, 20 August after the shooting, despite a statement that those who do not would risk being dismissed. However, a spokesperson for Lonmin said that 27% of its employees were at work. The chief financial officer for Lonmin, Simon Scott, said that "nobody will be asked to report for duty if the police consider them in danger of reprisals."[58] On 5 September, over 1,000 striking miners again protested at the mine and reiterated their demands for increased pay. There were dozens of police at the mine, while a helicopter hovered above the protesters.[59]

Despite an agreement between the National Union of Mineworkers and the mine, a majority of the 3,000 striking members from the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union continued to stay away from work. NUM's General-Secretary Frans Baleni said there had been a "high level of intimidation" had stopped other miners from returning to work. "The workers are still scared. There have been threats that those who have reported for duty would have their homes torched. Some of the workers also feel threatened by their managers. Peace has not really prevailed at this stage, which is the main reason why workers would stay away."[3] On 11 September, as another deadline to return to work passed, workers continued to stick their ground amid mounting solidarity protests.[60] Following President Jacob Zuma's vow to clamp down on protests at the mine on 14 September, military convoys and other armoured vehicles were seen in the area. The next day, demonstrations turned violent after the representatives of the striking miners refused to hand in their machetes, sticks and pistols. Police then fired tear gas on the protesters[61] in a shantytown. On 17 September, another march was stopped by police. At the same time COSATU was holding its annual congress with the issue on the top of its agenda.[62]

Other protests

There was a small protest outside parliament in Cape Town the day after the shootings.[why?][63] Two other mines also had similar protests, after the shooting, demanding a 300% salary increase. Police were present at the sites in case there was violence and to prevent an escalation of strikes. North West Province Premier Thandi Modise warned of spreading protests if the growing inequality gap was not dealt with. The same day Jacob Zuma visited the Marikana mine.[64]

On 4 September, the Gold Fields mine outside Johannesburg also had protests by mine workers. Neal Froneman, the C.E.O. of Gold One International who runs the mine, said that police were called to disperse the protesters. As a result of clashes that involved the stoning of a vehicle carrying others to work and tear gas and the firing of rubber bullets four people were injured. Froneman said: "Our security had to intervene, they used rubber bullets and police used rubber bullets and tear gas. Four people were slightly wounded and all have been released from the hospital." However, Pinky Tsinyane, a police spokesman, said that one of the injured workers was in critical condition; he added that four others had been arrested for public violence. The company spokesman, Sven Lunsche, further noted that about 12,000 of Gold Fields' workers "continue to engage in an unlawful and unprotected strike" that began on 28 August and, according to him, was the result of an internal dispute between the local union leaders and members of the National Union of Mineworkers.[65] As the solidarity protests spread to other mines, Julius Malema addressed a rally at the KDC Gold Fields mine, where a majority of the 15,000 workers were on strike. He said: "The strike at Marikana must go into all the mines. R12,500 is a reality. They must know, the mine bosses, that if they don't meet your demand, we're going to strike every month for five days, demanding R12,500."[60] As the body of a man hacked to death was found on the same day at the Marikana mine, Malema also called for a nationwide miners' strike.[66] On 16 September, about 1,000 miners in Rustenburg organised a solidarity march for the Marikana miners who marched the previous day. However, while this group was applying for a permit to demonstrate against police brutality the previous day, police helicopters encircled them in what was seen as intimidating leading to the miners dispersing.[67]

On 19 September, the same day as the announcement of a resolution to the Marikana strike, workers at Anglo American Platinum staged a strike demanding a similar offer at its Rustenberg mine. Mametlwe Sebei, a community representative, said in response to protests that at the mine "the mood here is upbeat, very celebratory. Victory is in sight. The workers are celebrating Lonmin as a victory." The strikers carried traditional weapons such as spears and machetes, before being dispersed by police using tear gas, stun grenades and rubber bullets against the "illegal gathering", according to police spokesman Dennis Adriao. Central Methodist Church Bishop Paul Verry said that one women who was struck by a bullet died. At the same time, an unnamed organiser for the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union of protests at Impala Platinum said: "We want management to meet us as well now. We want 9,000 rand a month as a basic wage instead of the roughly 5,000 rand we are getting."[3] Anglo Platinum then said in a statement that: "Anglo American Platinum has communicated to its employees the requirement to return to work by the night shift on Thursday 20 September, failing which legal avenues will be pursued."[3]

A wave of strikes occurred across the South African mining sector. As of early October analysts estimated that approximately 75,000 miners were on strike from various gold and platinum mines and companies across South Africa, most of them illegally.[15] Citing failure of workers to attend disciplinary hearings, on 5 October 2012, Anglo American Platinum—the world's biggest platinum producer—announced that it would fire 12,000 people.[68] It said it would so after losing 39,000 ounces in output – or 700 million rand ($82.3 million; £51 million) in revenue. The ANC Youth League expressed anger at the company and pledged solidarity with those who had been fired:

This action demonstrates the insensibility and insensitivity of the company... which has made astronomical profits on the blood, sweat and tears of the very same workers that today the company can just fire with impunity. Amplats is a disgrace and a disappointment to the country at large, a representation of white monopoly capital out of touch and uncaring of the plight of the poor.[15]

Reuters described the move as "a high-stakes attempt by the world's biggest platinum producer to push back at a wave of illegal stoppages sweeping through the country's mining sector and beyond".[69] The announcement triggered the rand falling to a 3 1⁄2-year low.[69] The events were expected to put further political pressure on President Jacob Zuma ahead of the leadership vote in December's ANC National Conference.[15][69]

Arrests

[icon] This section requires expansion. (September 2012)

Of the detained miners, 150 people claimed that they were beaten while in police custody.[70][71] In the middle of September, as police urged workers and five unnamed mines to return to work, they arrested 22 strikers for continued protesting.[3]

Mediation

The Ministry of Labour, Nelisiwe Oliphant, sought on 28 August to mediate an agreement to end the strike at a meeting set for the next day. However, the strikers reiterated their original demands of 12,500 rand a month, three times the current salary, saying that they had already sacrificed too much to settle for anything.[72] Mediation efforts were deadlocked, as of 6 September.[73] Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union President Joseph Mathunjwa later said: "When the employer is prepared to make an offer on the table, we shall make ourselves available", as he rejected an offer of mediation and vowed to continue striking till the miners' demands are met.[74]

On 10 September, negotiations were set to continue from noon. Lonmin's executive vice-president of human resources, Barnard Mokwena, said: "If workers don't come to work, we will still pursue the peace path. That is very, very necessary for us to achieve because this level of intimidation and people fearing for their lives obviously does not help anybody. For now it is a fragile process and we need to nurture it."[75]

On 18 September, Bishop Jo Seoka of the South African Council of Churches, who was mediating a resolution to the conflict, announced that the striking miners had accepted a 22% pay raise, a one-off payment of R2,000, and would return to work 20 September. However, the National Union of Mineworkers, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union and the Solidarity union did not make any statements in response to this offer.[76] While miners' representative Zolisa Bodlani said of the deal that "it's a huge achievement. No union has achieved a 22% increase before," Lonmin's Sue Vey said it would offer no comment as the agreement had not yet been signed. However, Chris Molebatsi, who was a part of the organising committee for the strike, said: "The campaign will go on. This campaign is aimed at helping workers. People died here at Marikana. Something needs to be done. This is a campaign to ensure justice for the people of Marikana. We want the culprits to be brought to book, and it is crucial that justice is seen to be done here. It is our duty and the duty of this country to ensure justice is served, so that we can make sure this country is a democracy and to stop South Africa from going down the drain." He also added that the Marikana Solidarity Campaign has more work to do in terms of supporting victims' families, offering PTSD counselling and to oversight the state-appointed judicial commission that would ensure justice after the violence; he also noted that:

During the past week people were taken from their homes and arrested by police, and people have been shot at. We need to ensure the safety of these people, and need to help stop police action against the people of Marikana. The work is enormous. Some people still need medical attention, and we also need to look at the living conditions of workers and the community at large. Then there is the problem of the unemployment of women and the high rate of illiteracy here. We need to help realise programmes to ensure people can get an income, that they can enjoy a reasonable standard of living.

At the same time, a Nomura International analyst for the sector said of the resolution that "the key worry now is that 22% wage rises will be seen spreading across the mine industry."[77]

The following day, however, confirmations of the agreement came from Lonmin and unions. Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration commissioner Afzul Soobedaar said: "We have reached an agreement that we have worked tirelessly for" and that the negotiations were an arduour process but congratulated all parties for being committed to reach a solution. National Union of Mineworker's negotiator Eric Gcilitshana said that there would now be stability at Lonmin with the return to work; while President of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Joseph Mathunjwa issued a statement that read: "This could have been done without losing lives." Lonmin spokesman in South Africa Abbey Kgotle said they were content with the resolution after difficult talks and that the agreement was dedicated to those killed. The final resolution entailed the miner working at the lowest depths earning between R9,611 from the previous R8,164, a winch operator would now earn R9,883 up from R8,931, a rock drill operator would earn R11,078 from R9,063 and a production team leader would earn R13,022 from R11,818.[78] The return to work on 20 September coincided with the last day of the COSATU conference in Midland, Johannesburg. At the same time, it was reported that an unnamed number of strikers left the unions that had previously represented them.[3]

Legal issues The 270 arrested miners were initially charged with "public violence." However, the charge was later changed to murder, despite the police having shot them. Justice Minister Jeff Radebe said that the decision "induced a sense of shock, panic and confusion. I have requested the acting National Director of Public Prosecutions (NDPP), advocate Nomgcobo Jiba[,] to furnish me with a report explaining the rationale behind such a decision."

The basis for prosecutions was said to be the doctrine of "common purpose." Although many have mentioned that the doctrine had previously been used by the apartheid government,[79] Professor James Grant, a senior lecturer in Criminal Law at Wits University, stated that, "...while common purpose was used and abused under apartheid, so was almost our entire legal system," and that "...it makes it exceedingly difficult to dismiss it as outdated apartheid law when it was endorsed in the Constitutional Court in 2003 in the case of S v Thebus. The Constitutional Court endorsed the requirements for common purpose set out in the case of S v Mgedezi, decided under apartheid in 1989."[80]

The legal representatives for the arrested 270 miners said their continued incarceration was "unlawful" as a special judicial inquiry that had been formed by Zuma was conducting its investigation. The law firm Maluleke, Msimang and Associates wrote an open letter to Zuma, on 30 August, saying that it would file an urgent petition with the High Court for the release of those imprisoned if he does not order their immediate release. "It is inconceivable that the South African state, of which you are the head, and any of its various public representatives, officials and citizens, can genuinely and honestly believe or even suspect that our clients murdered their own colleagues and in some cases, their own relatives."[81]

On 2 September, the National Prosecuting Authority announced that they would drop the murder charges against the 270 miners.[82] This followed Magistrate Esau Bodigelo telling his court in Ga-Rankuwa of the dropping of charges. At the same time, the first batch of the 270 arrested miners were released.[83] By 6 September, the second batch of over a 100 detainees were ordered released.[73]

Official inquiry

President Jacob Zuma commissioned an inquiry into the shooting to be headed by former Supreme Court of Appeals Judge Ian Farlam and tasked to "investigate matters of public, national and international concern arising out of the tragic incidents at the Lonmin Mine in Marikana." The hearings will begin at the Rustenburg Civic Centre and will question police, miners, union leaders, government employees and Lonmin employees about their conduct on the day.[84] The commission would have four months to hear evidence and testimony.

The commission began its work on 1 October. Amongst the first tasks was a hearing from two representatives of the miners who asked for a two-week postponement, which was rejected by Farlam. He also took a personal tour of the site of the protests. On the first day, he toured the site of the shootings hearing from the forensic expert who had examined the site and sat at the koppie (hill) where the miners hid from police. On the second day, he went to see the miners' dormitories—including where families can stay and an informal settlement. Al Jazeera's Tania Page said that the site had been cleaned since the incident and that the commission's challenge would be "to see the truth and find an objective balance when all the parties involved have had time to cover their tracks."[85]

South African judges holding an inquiry into the events were shown video and photographs of miners who lay died with handcuffs on as well as some photographs which a lawyer for the miners claimed to show that weapons such as a machete were planted by police next the dead miners after they had been shot.[86]

General reactions

During a trip to the European Union headquarters in Belgium on 18 September, President Jacob Zuma tried to reassure investors that though "we regarded the incident of Marikana as an unfortunate one. Nobody expected such an event." He further noted South Africa's handling of the conflict. European Council President Herman van Rompuy said: "The events at the Marikana mine were a tragedy and I welcome the judicial commission of inquiry set up by President Zuma," while he noted South Africa's growing influence. He also met with the President of the European Commission Jose Manuel Barroso. Meanwhile, EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht said: "I realise that this is a social conflict, this is completely within the remit of the South African legislation and the South African political system. But we are … deeply troubled by the fact of all these dead victims."[87]

The strikes were later said to be the result of inequality within South African society.[88]

Reactions to the shooting

South Africa

Government

President Jacob Zuma, who had been attending a regional summit in Mozambique at the time of the 16 August shootings, expressed "shock and dismay" at the violence and called on the unions to work with the government to "arrest the situation before it spirals out of control".[89] The day after the shootings, Jacob Zuma travelled to the location of the shootings and ordered a commission of inquiry to be formed, saying: "Today is not an occasion for blame, finger-pointing or recrimination."[43] Zuma also declared a week of national mourning for the strikers who were killed.[90]

National police commissioner Mangwashi Victoria Phiyega, a former social worker who was appointed on 13 June, stated police had acted in self-defense, saying, "This is no time for blaming, this is no time for finger-pointing. It is a time for us to mourn."[91] Phiyega presented aerial photography of the events which she claimed demonstrated that the strikers had advanced on the 500 strong police force before they had opened fire.[92]

The Ministry of Safety and Security issued a statement that read while protesting is legal, "these rights do not imply that people should be barbaric, intimidating and hold illegal gatherings." The ministry defended the police's actions, saying that this was a situation in which people were heavily armed and attacked.[36]

The Independent Police Investigative Directorate of South Africa (IPID) announced an investigation into the actions of the police force in the deaths : "The investigation will seek to establish if the police action was proportional to the threat posed by the miners. It is still too early in the investigation to establish the real facts around this tragedy."[93]

On 21 August, Defense Minister Nosiviwe Noluthando Mapisa-Nqakula became the first South African government official to apologise for the shooting and asked for forgiveness from angry miners who held up plastic packets of bullet casings to her. "We agree, as you see us standing in front of you here, that blood was shed at this place. We agree that it was not something to our liking and, as a representative of the government, I apologise...I am begging, I beg and I apologise, may you find forgiveness in your hearts."[94]

Opposition parties and politicians outside of the government[edit]

The opposition Democratic Alliance criticised the police action.[95]

Julius Malema – the former leader of the youth wing of the ANC, who had been suspended from the party four months prior to the incident- visited the scene of the shootings and called for Zuma to resign, stating, "How can he call on people to mourn those he has killed? He must step down."[96] He also said:

A responsible president says to the police you must keep order, but please act with restraint. He says to them use maximum force. He has presided over the killing of our people, and therefore he must step down. Not even [the] apartheid government killed some many people. [The government] had no right to shoot. We have to uncover the truth about what happened here. In this regard, I've decided to institute a commission of inquiry. The inquiry will enable us to get to the real cause of the incident and to derive the necessary lessons, too. It is clear there is something serious behind these happenings and that's why I have taken a decision to establish the commission because we must get to the truth. This is a shocking thing. We do not know where it comes from and we have to address it.

— Julius Malema, [97]

The South African Communist Party, which is in an alliance with the ruling ANC and COSATU, to which NUM is affiliated, called for the leaders of AMCU to be arrested.[98] AMCU blamed the NUM and the police and insisted that, contrary to various rumours, the union was not affiliated to any political party.[citation needed] Frans Baleni, the general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers, defended the police action to the Kaya FM radio station in saying: "The police were patient, but these people were extremely armed with dangerous weapons."[99]

Trade unions

The Congress of South African Trade Unions, a union federation to which the strikers are opposed,[28] supported the police account of events and said that the police had first used tear gas and water cannon on the miners, who then responded with "live ammunition".[100]

National Education, Health, and Allied Workers' Union spokesman Sizwe Pamla said after the tragedy "This atrocious and senseless killing of workers is deplorable and unnecessary. Our union feels Lonmin should be made to account for this tragedy. We also demand an investigation on the role of labor brokers in this whole [incident]. The remuneration and working conditions of miners also needed to be addressed, as these mining companies have been allowed to get away with murder for far too long. Our police service has adopted and perfected the apartheid tactics and the militarisation of the service, and encouraged the use of force to resolve disputes and conflicts. Police tactics and training needed to be reviewed in light of Thursday's shooting. The union demands that all police officers who deal with protests be taught disciplined ways of controlling protesters. We cannot afford to have a police force that is slaughtering protesters in the new dispensation."[101]

Speaking at a press briefing in Sandton after the confrontation, AMCU president Joseph Mathunjwa said management had reneged on commitments it had made to miners earlier in the week, claiming the shootings could have been avoided if management made good on their commitments to workers. Mthunjwa presented two documents in evidence mine management had indeed made commitments to the miners their grievances would be dealt with, but reneged, causing the violence. "Management could have stuck with their commitment. The commitment was once you're there peacefully at work, management will address your grievances through union structures," stated Mathnjwa, who noted he tried to help even though the confrontation did not involve his ACMU union. "This was an infight of the members of NUM with their offices. It's got nothing to do with AMCU.". Mathnjwa explained Amcu's leaders had been called to the site to intervene in the standoff between workers and the mine as a peaceful intermediary, even though the ACMU did not represent those involved in the dispute. "I pleaded with them. I said leave this place, they're going to kill you," said Mathunjwa, who later broke down in tears.[citation needed]

Mine owner

Mine owners Lonmin issued a statement following the shootings expressing regret for the loss of life, stressing the responsibility of the police for security during the strike and disassociating the violence from the industrial dispute.[102] Lonmin also said that the strikers must return to work on 20 August or possibly be dismissed.[90] Simon Scott, Lonmin's acting chief executive, following the incident said that the company needed to "rebuild the Lonmin brand and rebuild the platinum brand".[103] Workers rejected the company ultimatum to return to work and vowed to go ahead with their protests till their demands for wage increases were, as it would be an "insult" to the dead otherwise.[104] Lonmin then extended the deadline by 24 hours,[105] as Zuma called for a mourning period.[106][107]

When the strike began, Lonmin halted production and said that it was unlikely to fulfill its full-year guidance of 750,000 ounces (approx 21.25 metric tonnnes) of platinum. Lonmin said it will have to monitor its bank debt levels due to the disruption.[58] Lonmin's capacity to refinance its debt was also questioned.[108]

Strikers' families

Miners' families criticised the government's failure to produce a list of the dead two days after the incident, leaving many to worry whether missing members of their families were amongst those killed, wounded, or arrested during 16 August incident.[109]

Strikers and family members also blame NUM for starting the violence by shooting strikers on 11 August.[110][111]

Religious leaders

Church on Green Market Square in Cape Town, South Africa with a banner commemorating the Marikana massacre

A delegation from the National Inter-faith Council of South Africa (NIFC-SA) visited Marikana on 21 August to offer condolences and support to the community. The delegation included Rhema Church head, Pastor Ray McCauley and Catholic Archbishop of Johannesburg, Buti Tlhagale, and Chief Rabbi of South Africa, Warren Goldstein.[112]

Other

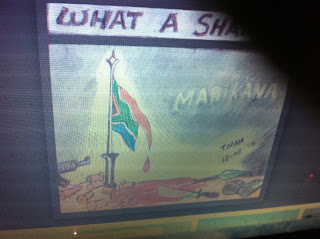

Protest art in Cape Town remembering one of the casualties[113]

The director of the Institute for Democracy in Africa, Paul Graham, asked "Why did South African policemen use live ammunition and interfere with a crime scene?" The director also criticised the independent commission of inquiry, stating, "It is very disappointing that those appointed to the commission of inquiry include cabinet ministers. They cannot be independent and will not be trusted."[103]

Oxford University lecturer in African Studies, and South African citizen, Jonny Steinberg, believes that the level of repression shown by the police could be a sign that President Jacob Zuma is attempting to appear strong and project authority over an increasingly fractured country and government prior to the ANC's internal party elections in December.[14]

Media

South African news media showed graphic footage and photos of the shootings, while the headlines included "Killing Field", "Mine Slaughter", and "Bloodbath". The newspaper Sowetan issued a front-page editorial, questioning what changed in South Africa since the fall of Apartheid in 1994, saying that this has happened in South Africa before under Apartheid when blacks were treated cruelly, and "it is continuing in a different guise now."[114]

Reuters described the incident as causing South Africa to question "its post-apartheid soul".[115] Mining Weekly.com said that the Lonmin killing would hurt South Africa as a destination for investment.[116] Bloomberg said that the clashes reflected unease over a growing wealth gap between the country's elite and workers such as those were protesting.[117] Al Jazeera asked if Zuma can withstand the controversy;[118] if the mine's links to the ruling ANC constituted an "economic apartheid;"[119] and whether the controversy over the shooting could resurrect the political career of Julius Malema, following his suspension from the ANC.[120]

Rehad Desai has made an awarded documentary about the events titled Miners Shot Down.[121] Desai was in a unique position to make the documentary as he was on site as the events took place. The 52 minute film contains live video of the shootings and the events leading to the situation starting one week prior and the immediate aftermath. Desai states that this incident is corrosive to democracy and that he fears nobody will be held accountable.[122]

International

Platinum financial market

Following the incident the spot price for platinum rose on world commodity markets.[123]

Political reactions

US Presidential Deputy Press Secretary Josh Earnest told reporters: "The American people are saddened at the tragic loss of life [at the Lonmin mines] and express our condolences to the families of those who have lost loved ones in this incident."[124] In Auckland, protesters attacked the South African embassy with paint bombs.[125]

Reactions to the resolution

Following the resolution of the Marikana strike, President Jacob Zuma expressed his relief following criticism from opposition parties and the media at his government's handling of the crisis. Union rivalry also widened as the resolution was touted as a victory for the AMCU over the bigger NUM. In financial markets, Lonmin's share prices initially rose by over 9%, but later receded as investors were made aware of the extra costs now incurred in wages while the company was already in the midst of struggling with its balance sheet and the unprofitable mine shafts. Platinum prices rose after falling 2.6% on 18 September on news of the deal.[3]

Literature

Peter Alexander and others: Marikana. A View from the Mountain and a Case to Answer, Jacana Media, Johannesburg, South Africa 2012, ISBN 978-1-431407330.

Marikana killings

Marikana massacre, Lonmin Strike

Lonmin-platinummyn, a, Marikana, Noordwes.jpg

The EPC section of Lonmin Platinum, with Bapong in the foreground

Location Marikana area, close to Rustenburg, South Africa

Participants Independent striking miners

National Union of Mineworkers

Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union

South African Police Service

Mine security

Lonmin

Deaths 14 August: 2

12–14 August: approx. 8 (police: 2, miners: 4, security guards: 2)[1][2]

16 August: 34 miners (78 miners wounded)

Later before resolution: 2

After 18 September resolution: 1[3]

Total:47

Marikana is located in South Africa MarikanaMarikana

Marikana in South Africa

The Marikana massacre[4] was the single most lethal use of force by South African security forces against civilians since 1960.[5] The shootings have been described as a massacre in the South African media and have been compared to the Sharpeville massacre in 1960.[6][7] The incident also took place on the 25-year anniversary of a nationwide South African miners' strike.[8]

Controversy emerged after it was discovered that most of the victims were shot in the back,[9][10] and many victims were shot far from police lines.[11] On 18 September, a mediator announced a resolution to the conflict, stating the striking miners had accepted a 22% pay rise, a one-off payment of 2,000 rand and would return to work 20 September.

The strike is considered a seminal event in modern South African history, and was followed by similar strikes at other mines across South Africa,[12][13] events which collectively made 2012 the most protest-filled year in the country since the end of apartheid.[14]

The Marikana massacre started as a wildcat strike at a mine owned by Lonmin in the Marikana area, close to Rustenburg, South Africa in 2012. The event garnered international attention following a series of violent incidents between the South African Police Service, Lonmin security and the leadership of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) on the one side and strikers themselves on the other, which resulted in the deaths of 44 people, 41 of whom were striking mineworkers killed by police. Also, during the same incident, at least 78 additional workers were injured. The total number of injuries during the strike remains unknown. In response to the Lonmin strikers, there were a wave of wildcat strikes across the South African mining sector.[15]

The first incidents of violence were reported to have started on 11 August after NUM leaders opened fire on NUM members who were on strike. Initial reports indicated that it was widely believed that two strikers died[16] that day; however, it later turned out that two strikers were seriously wounded, but not killed, in the shooting by NUM members.[17] This violence was followed by the death of another eight strikers, police and security personnel who were killed in the following three days.[18][19]

Contents

1 Background

2 First protests

3 Prior peaceful protests and fatal clashes

4 The 16 August massacre

4.1 Preliminary theories

4.2 Protester accounts

4.3 Police accounts

4.4 Eyewitness and journalist accounts

5 Following protests

6 Other protests

7 Arrests

8 Mediation

9 Legal issues

9.1 Official inquiry

10 General reactions

11 Reactions to the shooting

11.1 South Africa

11.1.1 Government

11.1.2 Opposition parties and politicians outside of the government

11.1.3 Trade unions

11.1.4 Mine owner

11.1.5 Strikers' families

11.1.6 Religious leaders

11.1.7 Other

11.2 Media

11.3 International

12 Reactions to the resolution

13 Literature

Background

The Bench Marks Foundation argued: "The benefits of mining are not reaching the workers or the surrounding communities. Lack of employment opportunities for local youth, squalid living conditions, unemployment and growing inequalities contribute to this mess."[20] It claimed the workers were exploited and this was a motivation for the violence. It also criticised the high profits when compared with the low wages of the workers. The International Labour Organisation criticised the condition of the miners saying they are exposed to "a variety of safety hazards: falling rocks, exposure to dust, intensive noise, fumes and high temperatures, among others."[21] Trade and Industry Minister Rob Davies described[when?] the conditions in the mines as "appalling" and said the owners who "make millions" had questions to answer about how they treat their workers.[22] It was later reported by Al Jazeera that the conditions in the mine led to "seething tensions" as a result of "dire living conditions, union rivalry, and company disinterest."[23]

Average price of platinum from 1992 to 2012 in US$ per troy ounce (~$20/g)[24]

Platinum is the main metal exploited in the Marikana mine.[25]

First protests

On 10 August 2012, rock drillers initiated a wildcat strike[26] in pursuit of a pay raise to 12,500 South African rand per month, a figure which amounted to tripling of their monthly salaries (from approx. US$500 to $1,500).[27][28]

The strike occurred against a backdrop of antagonism and violence between the African National Congress-allied National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and its emerging rival, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU). According to a Guardian columnist, the NUM was closely linked to the ruling ANC party but lost its organisational rights at the mine after its membership dropped from 66% to 49% and its leadership began to be seen as 'too close' to management.[29]

Prior peaceful protests and fatal clashes

At the Marikana platinum mine, operated by Lonmin at Nkaneng near Rustenburg, 3,000 workers walked off the job on 10 August after Lonmin failed to meet with workers.[18] On 11 August, NUM leaders allegedly opened fire on striking NUM members who were marching to their offices.[16][30][31] The killing of two miners was reported in the South African media as a central reason for the breakdown in trust within the union amongst workers.[32][33] Despite earlier contradictory reports, the clashes on the 11th are now acknowledged to be the first incidents of violence during the strike.[34]

Between 12 and 14 August, approximately nine people were killed in the area around Marikana. There are conflicting reports on who killed whom during these dates. However, at least four miners, two police officers, and two security guards seem to have been killed during this time.[35][36][37] During the Farlam Commission, the advocate for AMCU accused Lonmin of conspiring with police in killing two miners during a march back from Lonmin offices on 13 August, after which two police officers were also killed.[19]

Before the shootings, SAPS Captain Dennis Adriao told journalists: "We have tried over a number of days to negotiate with the leaders and with the gathering here at the mine, our objective is to get the people to surrender their weapons and to disperse peacefully."[38] However, submissions to the Farlam Commission dispute this, accusing police of failing to negotiate with strikers and participating in revenge killings.[39][40]

The Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union's Joseph Matunjwa said that the protests were in response to poor pay: "As long as bosses and senior management are getting fat cheques, that's good for them. And these workers are subjected to poverty for life. [After] 18 years of democracy, the mineworker is still earning 3,000 [South African Rand – approximately $360] under those harsh conditions underground."[41]

The 16 August massacre

On the afternoon of 16 August, members of a contingent of the South African Police Service, from an elite special unit,[42] opened fire with submachine guns (R5 rifles), on a group of strikers. Within minutes 34 miners were killed, and at least 78 were wounded.[43] The incident was the single most lethal use of force by South African security forces against civilians since the Sharpeville massacre during the apartheid era.[5]

Preliminary theories

Footage from several different angles shows that the police were pushing the strikers into a small area.[original research?] Groups of strikers began singing struggle songs, and marched along police lines. The police fired teargas and rubber bullets into these groups. At least one person in one group shot a handgun at the police. Members of this group either panicked or deliberately charged at a police line which sparked off the shooting.[44]

Protester accounts

[icon] This section requires expansion. (January 2014)

A year after the incident, review of the police reaction indicated:[45]

"Perhaps the most important lesson of Marikana is that the state can gun down dozens of black workers with little or no backlash from 'civil society', the judicial system or from within the institutions that supposedly form the bedrock of democracy. What we have instead is the farcical Farlam commission, an obvious attempt to clear the state's role in the massacre and prevent any sort of real investigation into the actions of the police on that day. In other words, the state can get away with mass murder, with apparent impunity in terms of institutional conceptions of justice and political accountability.

Police accounts

The South African Police Service said that the miners had refused a request to disarm and attacked them with various weapons including firearms taken from the two police officers killed earlier in the week.[46][47] South Africa's Police Commissioner, Mangwashi Victoria Phiyega claimed that the 500 strong police force was attacked by armed strikers, stating "The militant group stormed toward the police firing shots and wielding dangerous weapons."[48]

The day after the shooting Police Commissioner Phiyega released a statement giving a detailed account of the efforts taken by the police to avert the threat of a violent end to the stand-off. In the statement Commissioner Phiyega claims that the SAPS had on a number of occasions since the beginning of the week attempted to negotiate a peaceful end to the strike. Commissioner Phiyega also claims that the SAPS had begun receiving information that the crowd did not intend to leave peacefully and that a violent response from the miners was a likely outcome. At this point Commissioner Phiyega asserts that efforts were made to escalate defensive and crowd control measures by the deployment of concertina wire barricades and the use of water cannons, rubber bullets, stun grenades, and tear gas to break the strikers up and drive them into an area where they could better control them. It was at this point that Commissioner Phiyega claims that the efforts to gain control of the situation failed and the miners turned violent, attacking members of the SAPS. Commissioner Phiyega claims that members of the SAPS who were directly in the path of the attack had moved back in a defensive manner up until the point that it was believed that their safety was under threat, at which point they were cleared to use maximum force to halt the attack and protect themselves. Commissioner Phiyega said that the SAPS had acted well within their legislative mandate as outlined in Section 205 of the Constitution of South Africa.[49]

Advocate Ishmael Semenya, the lawyer for the police during official inquiry described the scale of the shooting when he stated on 6 November 2012 that "No more than 100 police officers discharged their firearms on 16 August. If the commission investigates the lawfulness of police conduct, then we could have to call 100 witnesses."[50]

Eyewitness and journalist accounts

According to the BBC, eyewitnesses reports suggest that "the shooting took place after a group of demonstrators, some holding clubs and machetes, rushed at a line of police officers".[51]

The Times reported that police did not use live ammunition until fired upon by a striking worker with a shotgun, and The Sowetan reported that striking miners appeared to have fired on the police, though the group which advanced towards the police appeared to be "peacefully gathering".[52] The Star journalist Poloko Tau said police maintained that they had been fired on first, but Tau did not see this firsthand.[52]

Siphiwe Sibeko, a Reuters photographer who was present at the scene, stated that he saw at least one of the protesters shoot a pistol before the police opened fire.[53]

Al Jazeera reported that the strikers had been forced by police in armoured vehicles with water cannons into an area surrounded by razor wire at which point the shooting began.[54]

The striking mine workers had gathered on 16 August on nearby Nkaneng Hill armed with spears, pangas (large machete-like knives) and sticks.[28] A large group of women, not employed at the mine, some armed with knobkerries, joined them. Six guns were found at the scene, one of which belonged to a police officer "hacked to death" earlier during the strike.[55]

Greg Marinovich examined the scene and found that the majority of victims were shot 300 meters from police lines where the main "charge" took place.[11] He claims that some of the victims “appear to have been shot at close range or crushed by police vehicles.” Some victims were shot in a "koppie" where they were cornered and could have been arrested. Due to local geography they must have been shot at close range. Few bullets were found in the surrounding area, suggesting they did not die in a hail of bullets. Marinovich concludes that “It is becoming clear to this reporter that heavily armed police hunted down and killed the miners in cold blood.”[9][56]

Following protests

The day after the shootings a group of miners' wives protested singing and chanting slogans and songs from the anti-apartheid struggle. They denied that the striking miners had shot first, insisted that the strike was about wages[citation needed] and demanded that the police officers responsible for the shooting be fired.[57]

Most of the approximately 28,000 employees at the mine did not go to work on Monday, 20 August after the shooting, despite a statement that those who do not would risk being dismissed. However, a spokesperson for Lonmin said that 27% of its employees were at work. The chief financial officer for Lonmin, Simon Scott, said that "nobody will be asked to report for duty if the police consider them in danger of reprisals."[58] On 5 September, over 1,000 striking miners again protested at the mine and reiterated their demands for increased pay. There were dozens of police at the mine, while a helicopter hovered above the protesters.[59]

Despite an agreement between the National Union of Mineworkers and the mine, a majority of the 3,000 striking members from the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union continued to stay away from work. NUM's General-Secretary Frans Baleni said there had been a "high level of intimidation" had stopped other miners from returning to work. "The workers are still scared. There have been threats that those who have reported for duty would have their homes torched. Some of the workers also feel threatened by their managers. Peace has not really prevailed at this stage, which is the main reason why workers would stay away."[3] On 11 September, as another deadline to return to work passed, workers continued to stick their ground amid mounting solidarity protests.[60] Following President Jacob Zuma's vow to clamp down on protests at the mine on 14 September, military convoys and other armoured vehicles were seen in the area. The next day, demonstrations turned violent after the representatives of the striking miners refused to hand in their machetes, sticks and pistols. Police then fired tear gas on the protesters[61] in a shantytown. On 17 September, another march was stopped by police. At the same time COSATU was holding its annual congress with the issue on the top of its agenda.[62]

Other protests

There was a small protest outside parliament in Cape Town the day after the shootings.[why?][63] Two other mines also had similar protests, after the shooting, demanding a 300% salary increase. Police were present at the sites in case there was violence and to prevent an escalation of strikes. North West Province Premier Thandi Modise warned of spreading protests if the growing inequality gap was not dealt with. The same day Jacob Zuma visited the Marikana mine.[64]

On 4 September, the Gold Fields mine outside Johannesburg also had protests by mine workers. Neal Froneman, the C.E.O. of Gold One International who runs the mine, said that police were called to disperse the protesters. As a result of clashes that involved the stoning of a vehicle carrying others to work and tear gas and the firing of rubber bullets four people were injured. Froneman said: "Our security had to intervene, they used rubber bullets and police used rubber bullets and tear gas. Four people were slightly wounded and all have been released from the hospital." However, Pinky Tsinyane, a police spokesman, said that one of the injured workers was in critical condition; he added that four others had been arrested for public violence. The company spokesman, Sven Lunsche, further noted that about 12,000 of Gold Fields' workers "continue to engage in an unlawful and unprotected strike" that began on 28 August and, according to him, was the result of an internal dispute between the local union leaders and members of the National Union of Mineworkers.[65] As the solidarity protests spread to other mines, Julius Malema addressed a rally at the KDC Gold Fields mine, where a majority of the 15,000 workers were on strike. He said: "The strike at Marikana must go into all the mines. R12,500 is a reality. They must know, the mine bosses, that if they don't meet your demand, we're going to strike every month for five days, demanding R12,500."[60] As the body of a man hacked to death was found on the same day at the Marikana mine, Malema also called for a nationwide miners' strike.[66] On 16 September, about 1,000 miners in Rustenburg organised a solidarity march for the Marikana miners who marched the previous day. However, while this group was applying for a permit to demonstrate against police brutality the previous day, police helicopters encircled them in what was seen as intimidating leading to the miners dispersing.[67]

On 19 September, the same day as the announcement of a resolution to the Marikana strike, workers at Anglo American Platinum staged a strike demanding a similar offer at its Rustenberg mine. Mametlwe Sebei, a community representative, said in response to protests that at the mine "the mood here is upbeat, very celebratory. Victory is in sight. The workers are celebrating Lonmin as a victory." The strikers carried traditional weapons such as spears and machetes, before being dispersed by police using tear gas, stun grenades and rubber bullets against the "illegal gathering", according to police spokesman Dennis Adriao. Central Methodist Church Bishop Paul Verry said that one women who was struck by a bullet died. At the same time, an unnamed organiser for the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union of protests at Impala Platinum said: "We want management to meet us as well now. We want 9,000 rand a month as a basic wage instead of the roughly 5,000 rand we are getting."[3] Anglo Platinum then said in a statement that: "Anglo American Platinum has communicated to its employees the requirement to return to work by the night shift on Thursday 20 September, failing which legal avenues will be pursued."[3]

A wave of strikes occurred across the South African mining sector. As of early October analysts estimated that approximately 75,000 miners were on strike from various gold and platinum mines and companies across South Africa, most of them illegally.[15] Citing failure of workers to attend disciplinary hearings, on 5 October 2012, Anglo American Platinum—the world's biggest platinum producer—announced that it would fire 12,000 people.[68] It said it would so after losing 39,000 ounces in output – or 700 million rand ($82.3 million; £51 million) in revenue. The ANC Youth League expressed anger at the company and pledged solidarity with those who had been fired:

This action demonstrates the insensibility and insensitivity of the company... which has made astronomical profits on the blood, sweat and tears of the very same workers that today the company can just fire with impunity. Amplats is a disgrace and a disappointment to the country at large, a representation of white monopoly capital out of touch and uncaring of the plight of the poor.[15]

Reuters described the move as "a high-stakes attempt by the world's biggest platinum producer to push back at a wave of illegal stoppages sweeping through the country's mining sector and beyond".[69] The announcement triggered the rand falling to a 3 1⁄2-year low.[69] The events were expected to put further political pressure on President Jacob Zuma ahead of the leadership vote in December's ANC National Conference.[15][69]

Arrests

[icon] This section requires expansion. (September 2012)

Of the detained miners, 150 people claimed that they were beaten while in police custody.[70][71] In the middle of September, as police urged workers and five unnamed mines to return to work, they arrested 22 strikers for continued protesting.[3]

Mediation

The Ministry of Labour, Nelisiwe Oliphant, sought on 28 August to mediate an agreement to end the strike at a meeting set for the next day. However, the strikers reiterated their original demands of 12,500 rand a month, three times the current salary, saying that they had already sacrificed too much to settle for anything.[72] Mediation efforts were deadlocked, as of 6 September.[73] Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union President Joseph Mathunjwa later said: "When the employer is prepared to make an offer on the table, we shall make ourselves available", as he rejected an offer of mediation and vowed to continue striking till the miners' demands are met.[74]

On 10 September, negotiations were set to continue from noon. Lonmin's executive vice-president of human resources, Barnard Mokwena, said: "If workers don't come to work, we will still pursue the peace path. That is very, very necessary for us to achieve because this level of intimidation and people fearing for their lives obviously does not help anybody. For now it is a fragile process and we need to nurture it."[75]

On 18 September, Bishop Jo Seoka of the South African Council of Churches, who was mediating a resolution to the conflict, announced that the striking miners had accepted a 22% pay raise, a one-off payment of R2,000, and would return to work 20 September. However, the National Union of Mineworkers, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union and the Solidarity union did not make any statements in response to this offer.[76] While miners' representative Zolisa Bodlani said of the deal that "it's a huge achievement. No union has achieved a 22% increase before," Lonmin's Sue Vey said it would offer no comment as the agreement had not yet been signed. However, Chris Molebatsi, who was a part of the organising committee for the strike, said: "The campaign will go on. This campaign is aimed at helping workers. People died here at Marikana. Something needs to be done. This is a campaign to ensure justice for the people of Marikana. We want the culprits to be brought to book, and it is crucial that justice is seen to be done here. It is our duty and the duty of this country to ensure justice is served, so that we can make sure this country is a democracy and to stop South Africa from going down the drain." He also added that the Marikana Solidarity Campaign has more work to do in terms of supporting victims' families, offering PTSD counselling and to oversight the state-appointed judicial commission that would ensure justice after the violence; he also noted that:

During the past week people were taken from their homes and arrested by police, and people have been shot at. We need to ensure the safety of these people, and need to help stop police action against the people of Marikana. The work is enormous. Some people still need medical attention, and we also need to look at the living conditions of workers and the community at large. Then there is the problem of the unemployment of women and the high rate of illiteracy here. We need to help realise programmes to ensure people can get an income, that they can enjoy a reasonable standard of living.

At the same time, a Nomura International analyst for the sector said of the resolution that "the key worry now is that 22% wage rises will be seen spreading across the mine industry."[77]

The following day, however, confirmations of the agreement came from Lonmin and unions. Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration commissioner Afzul Soobedaar said: "We have reached an agreement that we have worked tirelessly for" and that the negotiations were an arduour process but congratulated all parties for being committed to reach a solution. National Union of Mineworker's negotiator Eric Gcilitshana said that there would now be stability at Lonmin with the return to work; while President of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Joseph Mathunjwa issued a statement that read: "This could have been done without losing lives." Lonmin spokesman in South Africa Abbey Kgotle said they were content with the resolution after difficult talks and that the agreement was dedicated to those killed. The final resolution entailed the miner working at the lowest depths earning between R9,611 from the previous R8,164, a winch operator would now earn R9,883 up from R8,931, a rock drill operator would earn R11,078 from R9,063 and a production team leader would earn R13,022 from R11,818.[78] The return to work on 20 September coincided with the last day of the COSATU conference in Midland, Johannesburg. At the same time, it was reported that an unnamed number of strikers left the unions that had previously represented them.[3]

Legal issues The 270 arrested miners were initially charged with "public violence." However, the charge was later changed to murder, despite the police having shot them. Justice Minister Jeff Radebe said that the decision "induced a sense of shock, panic and confusion. I have requested the acting National Director of Public Prosecutions (NDPP), advocate Nomgcobo Jiba[,] to furnish me with a report explaining the rationale behind such a decision."

The basis for prosecutions was said to be the doctrine of "common purpose." Although many have mentioned that the doctrine had previously been used by the apartheid government,[79] Professor James Grant, a senior lecturer in Criminal Law at Wits University, stated that, "...while common purpose was used and abused under apartheid, so was almost our entire legal system," and that "...it makes it exceedingly difficult to dismiss it as outdated apartheid law when it was endorsed in the Constitutional Court in 2003 in the case of S v Thebus. The Constitutional Court endorsed the requirements for common purpose set out in the case of S v Mgedezi, decided under apartheid in 1989."[80]

The legal representatives for the arrested 270 miners said their continued incarceration was "unlawful" as a special judicial inquiry that had been formed by Zuma was conducting its investigation. The law firm Maluleke, Msimang and Associates wrote an open letter to Zuma, on 30 August, saying that it would file an urgent petition with the High Court for the release of those imprisoned if he does not order their immediate release. "It is inconceivable that the South African state, of which you are the head, and any of its various public representatives, officials and citizens, can genuinely and honestly believe or even suspect that our clients murdered their own colleagues and in some cases, their own relatives."[81]

On 2 September, the National Prosecuting Authority announced that they would drop the murder charges against the 270 miners.[82] This followed Magistrate Esau Bodigelo telling his court in Ga-Rankuwa of the dropping of charges. At the same time, the first batch of the 270 arrested miners were released.[83] By 6 September, the second batch of over a 100 detainees were ordered released.[73]

Official inquiry

President Jacob Zuma commissioned an inquiry into the shooting to be headed by former Supreme Court of Appeals Judge Ian Farlam and tasked to "investigate matters of public, national and international concern arising out of the tragic incidents at the Lonmin Mine in Marikana." The hearings will begin at the Rustenburg Civic Centre and will question police, miners, union leaders, government employees and Lonmin employees about their conduct on the day.[84] The commission would have four months to hear evidence and testimony.

The commission began its work on 1 October. Amongst the first tasks was a hearing from two representatives of the miners who asked for a two-week postponement, which was rejected by Farlam. He also took a personal tour of the site of the protests. On the first day, he toured the site of the shootings hearing from the forensic expert who had examined the site and sat at the koppie (hill) where the miners hid from police. On the second day, he went to see the miners' dormitories—including where families can stay and an informal settlement. Al Jazeera's Tania Page said that the site had been cleaned since the incident and that the commission's challenge would be "to see the truth and find an objective balance when all the parties involved have had time to cover their tracks."[85]

South African judges holding an inquiry into the events were shown video and photographs of miners who lay died with handcuffs on as well as some photographs which a lawyer for the miners claimed to show that weapons such as a machete were planted by police next the dead miners after they had been shot.[86]

General reactions

During a trip to the European Union headquarters in Belgium on 18 September, President Jacob Zuma tried to reassure investors that though "we regarded the incident of Marikana as an unfortunate one. Nobody expected such an event." He further noted South Africa's handling of the conflict. European Council President Herman van Rompuy said: "The events at the Marikana mine were a tragedy and I welcome the judicial commission of inquiry set up by President Zuma," while he noted South Africa's growing influence. He also met with the President of the European Commission Jose Manuel Barroso. Meanwhile, EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht said: "I realise that this is a social conflict, this is completely within the remit of the South African legislation and the South African political system. But we are … deeply troubled by the fact of all these dead victims."[87]

The strikes were later said to be the result of inequality within South African society.[88]

Reactions to the shooting

South Africa

Government

President Jacob Zuma, who had been attending a regional summit in Mozambique at the time of the 16 August shootings, expressed "shock and dismay" at the violence and called on the unions to work with the government to "arrest the situation before it spirals out of control".[89] The day after the shootings, Jacob Zuma travelled to the location of the shootings and ordered a commission of inquiry to be formed, saying: "Today is not an occasion for blame, finger-pointing or recrimination."[43] Zuma also declared a week of national mourning for the strikers who were killed.[90]

National police commissioner Mangwashi Victoria Phiyega, a former social worker who was appointed on 13 June, stated police had acted in self-defense, saying, "This is no time for blaming, this is no time for finger-pointing. It is a time for us to mourn."[91] Phiyega presented aerial photography of the events which she claimed demonstrated that the strikers had advanced on the 500 strong police force before they had opened fire.[92]

The Ministry of Safety and Security issued a statement that read while protesting is legal, "these rights do not imply that people should be barbaric, intimidating and hold illegal gatherings." The ministry defended the police's actions, saying that this was a situation in which people were heavily armed and attacked.[36]

The Independent Police Investigative Directorate of South Africa (IPID) announced an investigation into the actions of the police force in the deaths : "The investigation will seek to establish if the police action was proportional to the threat posed by the miners. It is still too early in the investigation to establish the real facts around this tragedy."[93]

On 21 August, Defense Minister Nosiviwe Noluthando Mapisa-Nqakula became the first South African government official to apologise for the shooting and asked for forgiveness from angry miners who held up plastic packets of bullet casings to her. "We agree, as you see us standing in front of you here, that blood was shed at this place. We agree that it was not something to our liking and, as a representative of the government, I apologise...I am begging, I beg and I apologise, may you find forgiveness in your hearts."[94]

Opposition parties and politicians outside of the government[edit]

The opposition Democratic Alliance criticised the police action.[95]

Julius Malema – the former leader of the youth wing of the ANC, who had been suspended from the party four months prior to the incident- visited the scene of the shootings and called for Zuma to resign, stating, "How can he call on people to mourn those he has killed? He must step down."[96] He also said:

A responsible president says to the police you must keep order, but please act with restraint. He says to them use maximum force. He has presided over the killing of our people, and therefore he must step down. Not even [the] apartheid government killed some many people. [The government] had no right to shoot. We have to uncover the truth about what happened here. In this regard, I've decided to institute a commission of inquiry. The inquiry will enable us to get to the real cause of the incident and to derive the necessary lessons, too. It is clear there is something serious behind these happenings and that's why I have taken a decision to establish the commission because we must get to the truth. This is a shocking thing. We do not know where it comes from and we have to address it.

— Julius Malema, [97]

The South African Communist Party, which is in an alliance with the ruling ANC and COSATU, to which NUM is affiliated, called for the leaders of AMCU to be arrested.[98] AMCU blamed the NUM and the police and insisted that, contrary to various rumours, the union was not affiliated to any political party.[citation needed] Frans Baleni, the general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers, defended the police action to the Kaya FM radio station in saying: "The police were patient, but these people were extremely armed with dangerous weapons."[99]

Trade unions