BLACK SOCIAL HISTORY

Faustin Soulouque

| Faustin I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor of Haiti | |||||

Faustin I, in 1850

| |||||

| Emperor of Haiti | |||||

| Reign | 25 August 1849 – 15 January 1859 | ||||

| Coronation | 18 April 1852 | ||||

| Predecessor | Himself (as President of Haiti) | ||||

| Successor | Fabre Geffrard (as President of Haiti) | ||||

| 7th President of Haiti | |||||

| Reign | 1 March 1847 – 25 August 1849 | ||||

| Predecessor | Jean-Baptiste Riché | ||||

| Successor | Himself (as emperor of Haiti) | ||||

| Spouse | Adélina Lévêque | ||||

| Issue | Célita Soulouque Olive Soulouque (adopted) | ||||

| |||||

| Mother | Marie-Catherine Soulouque | ||||

| Born | 15 August 1782 Petit-Goave, Saint-Domingue | ||||

| Died | 6 August 1867 (aged 84) Anse-à-Veau, Haiti | ||||

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (15 August 1782 – 6 August 1867[1]) was a career officer and general in the Haitian Army when he was elected President of Haiti in 1847. In 1849 he was proclaimed Emperor of Haiti under the name Faustin I. He soon purged the army of the ruling elite, installed black loyalists in administrative positions, and created a secret police and a personal army. In 1849 he created a black nobility in the country. However, his unsuccessful attempts to reconquer the neighbouring Dominican Republicundermined his control and a conspiracy led by General Fabre Nicolas Geffrard forced him to abdicate in 1859.[2]

Early years

Born into slavery in Petit-Goâve in 1782, Soulouque was one of two sons of Marie-Catherine Soulouque. The latter was born at Port-au-Prince, Saint-Domingue, 1744, as a creole slave of the Mandingo race. She died at Port-au-Prince, 9 August 1819. He was freed as a result of a 1793 decree of Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, the Civil Commissioner of the French colony of Saint-Domingue, that abolished slavery in response to slave revolts in 1791. As a free citizen, and with his freedom in serious jeopardy due to attempts of the French government to re-establish slavery in its colony of Saint-Domingue, he enlisted in the black revolutionary army to fight as a private during the Haitian Revolution between 1803–1804. During this conflict, Soulouque became a respected soldier and as a consequence he was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the Army of Haiti in 1806 and made aide-de-camp to General Lamarre.

In 1810 he was appointed to the Horse Guards under President Pétion. During the next four decades he continued to serve in the Haitian Military, rising to the rank of Colonel under President Guerrier, until finally promoted to the highest command in the Haitian Army, attaining the rank of Lieutenant General and Supreme Commander of the Presidential Guards under then President Jean-Baptiste Riché.

Reign

In 1847 President Riché died. During his tenure he had acted as a figurehead for the Boyerist ruling class, who immediately began to look for a replacement. Their attention quickly focused on Faustin Soulouque, whom the majority considered to be a somewhat dull and ignorant man. At the age of 65 he seemed to be a malleable candidate and was subsequently enticed to accept the role offered him, taking the Presidential Oath of Office on 2 March 1847.

At first Faustin seemed to fill the role of puppet well. He retained the cabinet-level ministers of the former president and continued the programs of his predecessor. Within a short time however, he overthrew his backers and made himself absolute ruler of the Haitian state. According to the book A Continent Of Islands: Searching For The Caribbean Destiny by Mark Kurlansky: “He organized a private militia, the Zinglins, and proceeded to arrest, kill, and burn out anyone who opposed him, especially mulattoes, thus consolidating his power over the government. This process included a massacre of the mulattoes in Port-au-Prince on 16 April 1848,[3] and culminated in the Senate and Chamber of Deputies proclaiming him Emperor of Haiti on 26 August 1849.

Soulouque also invited black Louisianans to immigrate to Haiti. Haitian-educated Emile Desdunes, an Afro-Creole native New Orleanian, acted as an agent for Soulouque and arranged free transportation to Haiti in 1859 for at least 350 desperate evacuees. A large number of these refugees later returned to Louisiana.

Soulouque's reign was marked by a violent restrictions towards opposition and numerous murders. The fact that Soulouque was an open adherent of the African Vodou religion, contributed to his violent reputation.[4] During his reign Soulouque was the victim of prejudice and discrimination against creoles by Victorian scribblers.

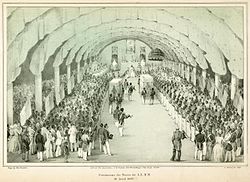

Coronation

Soulouque paid £2,000 for his crown, and spent £30,000 for the rest of the accessories (according to Sir Spenser St John, British charge d’affaires in Haiti during the 1860s in his account: "Hayti, or, The Black Republic", pp. 95–96). Gustave d’Alaux describes this event in his book, Soulouque and his Empire: “His Imperial Majesty had the principal merchant of Port-au-Prince called, one morning, and commanded him to order, immediately, from Paris, a costume, in every particular like that he admired in representing the ceremonies of Napoleon’s coronation. Faustin I, besides, ordered, for himself, a crown – one for the Empress – a sceptre, globe, hand-of-justice, throne, and all other accessories, all to be like those used in the coronation of Napoleon.". In December 1849 Faustin married his long-time companion Adélina Lévêque. On 18 April 1852 at the capital Port-au-Prince, both emperor and empress were crowned in an immense and lavish ceremony in emulation of the coronation of the French Emperor Napoleon I. The president of the Senate, attached to the breast of the Emperor, a large decoration, passed a chain about the neck of the Empress – and, pronounced his address; to which His Majesty Faustin replied with spirit: “Vive la liberté, vive l'égalité!” (Gustave d’Alaux). The coronation is illustrated in the 'Album Impériale d'Haïti', engraved by Severyn, published New York, 1852 (available in the British Library).

Nobility

During his subsequent reign, Faustin attempted to create a strong centralized government, which while retaining a profoundly Haitian character, borrowed heavily from European traditions, especially those of the First French Empire. One of his first acts after being declared emperor was to establish a Haitian nobility. The Constitution of 20 September 1849 granted the Emperor the right to create hereditary titles and confer other honours on his subjects. Volumes 5 and 6 of John Saunders and Westland Marston’s The National magazine (published in 1859) stated the empire consisted of 4 princes, 59 dukes, 90 earls, 30 lady knights (but no male knights), 250 barons, and 2 marchionesses. The first patents were issued by Emperor Faustin on 21 December 1850. Other sources add "trent cent Chevaliers" and "quatre cents nobles" to this list.[5] Subsequent creations extended the number of noble titles. Titles issued by king Henry Christophe were sometimes reissued by Faustin. As an example the title of Comte du Terrier-Rouge was issued to Charles Pierre under Christophe (The Armorial of Haiti, College of Arms, London 2007, p. 78) and the same title was issued under Soulouque on behalf of general Guerrier de Prophete (Java-Bode 5 August 1857). In order that he might reward loyalty to his regime as well as add to the prestige of the Haitian Monarchy, he established the Military Order of St. Faustin and the Civil Order of the Haitian Legion of Honor on 21 September 1849. Later, he created the Orders of St. Mary Magdalene and the Order of St. Anne in 1856. That same year he founded the Imperial Academy of Arts.

Politics

Faustin's foreign policy was centered on preventing foreign intrusion into Haitian politics and sovereignty. The independence of theDominican Republic (then called Santo Domingo) during the Dominican War of Independence from Haiti was, in his view, a direct threat to that security. Faustin launched successive invasions into Dominican territory, in 1849, 1850, 1855 and 1856, each with the objective of seizing the eastern half of the island and annexing it to Haiti. However, all of the attempts ended in defeat for the Haitian Army.

During his reign, Faustin also found himself in direct confrontation with the United States over Navassa Island, which the United States had seized on the somewhat dubious grounds that guano had been discovered there. Faustin dispatched warships to the island in response to the incursion, but withdrew them after the United States guaranteed Haiti a portion of the revenues from the mining operations.

The question of who Soulouque really was, is heavily disputed. Virtually no official government records of cabinet meetings exists. According to Latin American scholar Murdo J. MacLeod ("The Soulouque Regime In Haiti -- 1847 - 1859: A Reevaluation.", Caribbean Studies/Vo. 10. No. 3): "We are left with his policies as they are discernible, with an assessment of the men whom he used to govern, and with our evaluation of how correct his appreciation of the situation really was. In every case we must conclude that Faustin Soulouque was a man of high intelligence, a realist, a pragmatist, and a superb, if ruthless politician and diplomat. There is no denying his patriotism and his ability to impose domestic tranquility.".

Line of succession

Faustin's marriage to Empress Adélina produced one daughter, Princess Célita Soulouque. The emperor also adopted Adélina's daughter, Olive, in 1850. She was granted the title of Princess with the style Her Serene Highness. Célita married Jean Philippe Lubin, Count of Pétionville,[6] and had issue. The emperor had one brother, Prince Jean-Joseph Soulouque, who in turn had eleven sons and daughters. The Constitution of 20 September 1849 made the Imperial Dignity hereditary amongst the natural and legitimate direct descendants of Emperor Faustin I, by order of primogeniture and to the perpetual exclusion of females. The Emperor could adopt the children or grandchildren of his brothers, and become members of his family from the date of adoption. Sons so adopted enjoyed the right of succession to the throne, immediately after the Emperor's natural and legitimate sons.[5] Jean-Joseph's eldest son, Prince Mainville-Joseph Soulouque,[7] was created Prince Imperial of Haiti and heir apparent upon the succession of his uncle to the throne. His relation with Marie d'Albert produced a daughter, Marie Adelina Soulouque "princesse imperial d'Haiti".[8] His marriage In 1854 with Faustin's adopted daughter Olivia produced three children: "S.A.S. la princesse" Maria Soulouque, "S.A.I. le prince" Joseph Soulouque, "prince impérial", pretender to the throne as Joseph I, and "S.A.S. le prince" Faustin-Joseph Soulouque.

Exile and death

In 1858 a revolution began, led by General Fabre Geffrard, Duc de Tabara. In December of that year, Geffrard defeated the Imperial Army and seized control of most of the country. On the night of December 20, 1858, he left Port-au-Prince in a small boat, accompanied only by his son and two trusty followers, Ernest Roumain and Jean-Bart. On the 22d he arrived at Gonaives, where the insurrection broke out. The Republic was acclaimed and the Constitution of 1846 was adopted. On the 23d of December the Departmental Committee, which had been organized, divested Faustin Soulouque of his office and appointed Fabre Geffrard President of Haiti. Cap-Haitien and the whole Department of Artibonite joined in the restoration of the Republic. As a result the emperor abdicated his throne on 15 January 1859. Refused aid by the French Legation, Faustin was taken into exile aboard a British warship on 22 January 1859. Soon afterwards, the emperor and his family arrived in Kingston, Jamaica, where they remained for several years. Some records claim that he died in Kingston. But, according to Haitian historian Jacques Nicolas Léger in his book Haiti, her History and her Detractors, Emperor Faustin actually died inPetit-Goave in August 1867, having had returned to Haiti at some point.

No comments:

Post a Comment